After World War II, Italy embarked on a process of modernization that also extended to urban signage in cities. This period was marked by increasing urbanization and a significant increase in vehicular traffic, making more effective regulation of road circulation essential.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the expansion of cities and the growing number of vehicles highlighted the need for more detailed and specific signage, reflecting the increasing focus on pedestrian safety. During this time, the historic Touring Club Italiano (whose current logo was redesigned by Bob Noorda in 1978, with Franco Grignani among those submitting alternative proposals) continued to promote standardized signage to improve mobility for motorists and cyclists, emerging user groups of the era.

The evolution of urban signage in Italy can also be observed through iconic projects that set new standards for visual communication in cities. Among these, the signage system of the Milan Metro (Subway) – designed by Bob Noorda and awarded the prestigious ‘Compasso d’Oro’ in 1964 – played a pivotal role. It was aligned with other international examples, such as the 1972 New York City Subway signage designed by Massimo Vignelli and Bob Noorda, where similar principles of clarity, legibility, and uniformity were applied to manage highly complex systems.

These projects were not merely functional but also represented a design aesthetic that became a hallmark of Italian modernism. Urban signage began to be perceived not just as a means of providing information but as an integral part of architecture and urban identity.

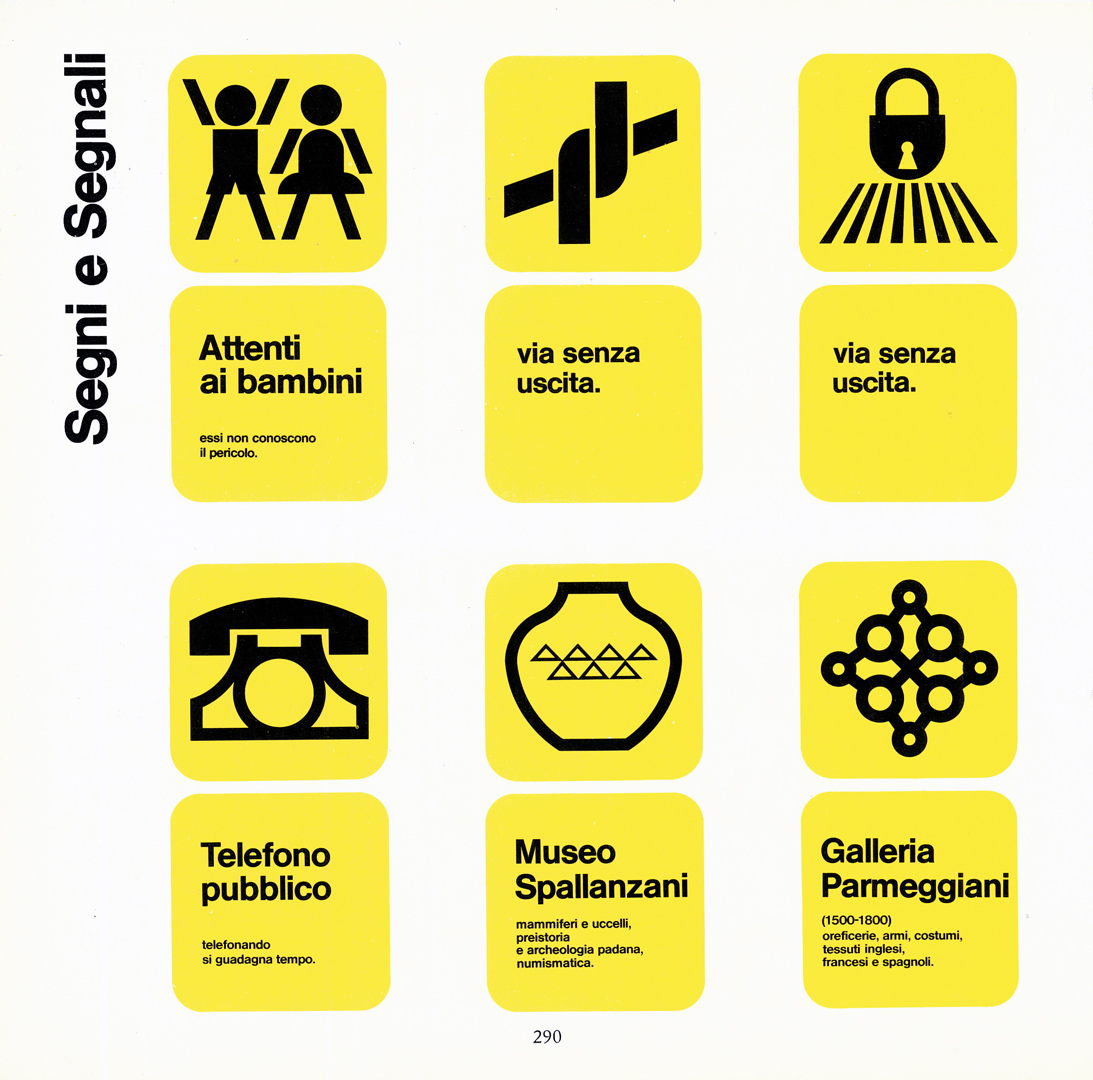

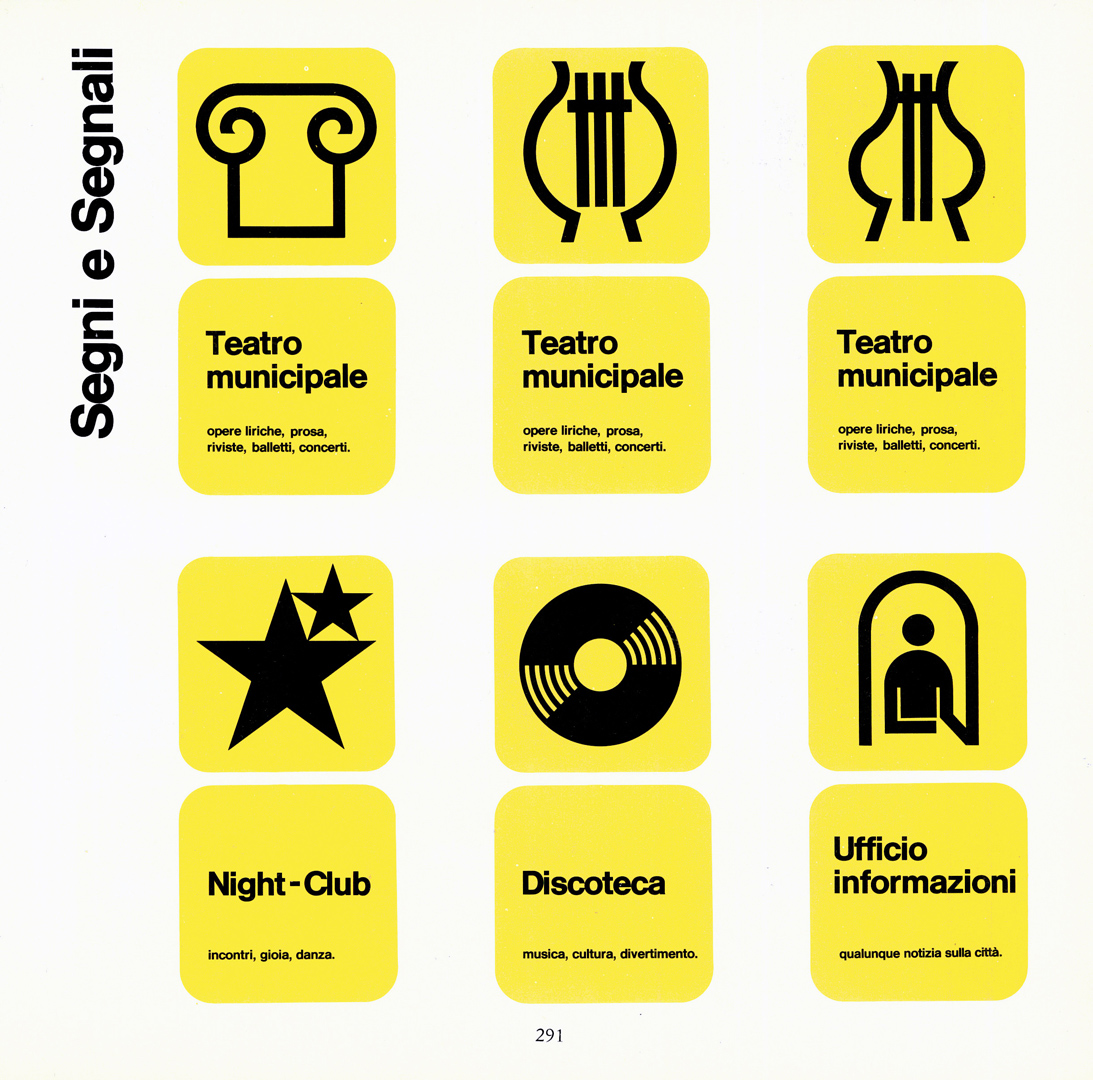

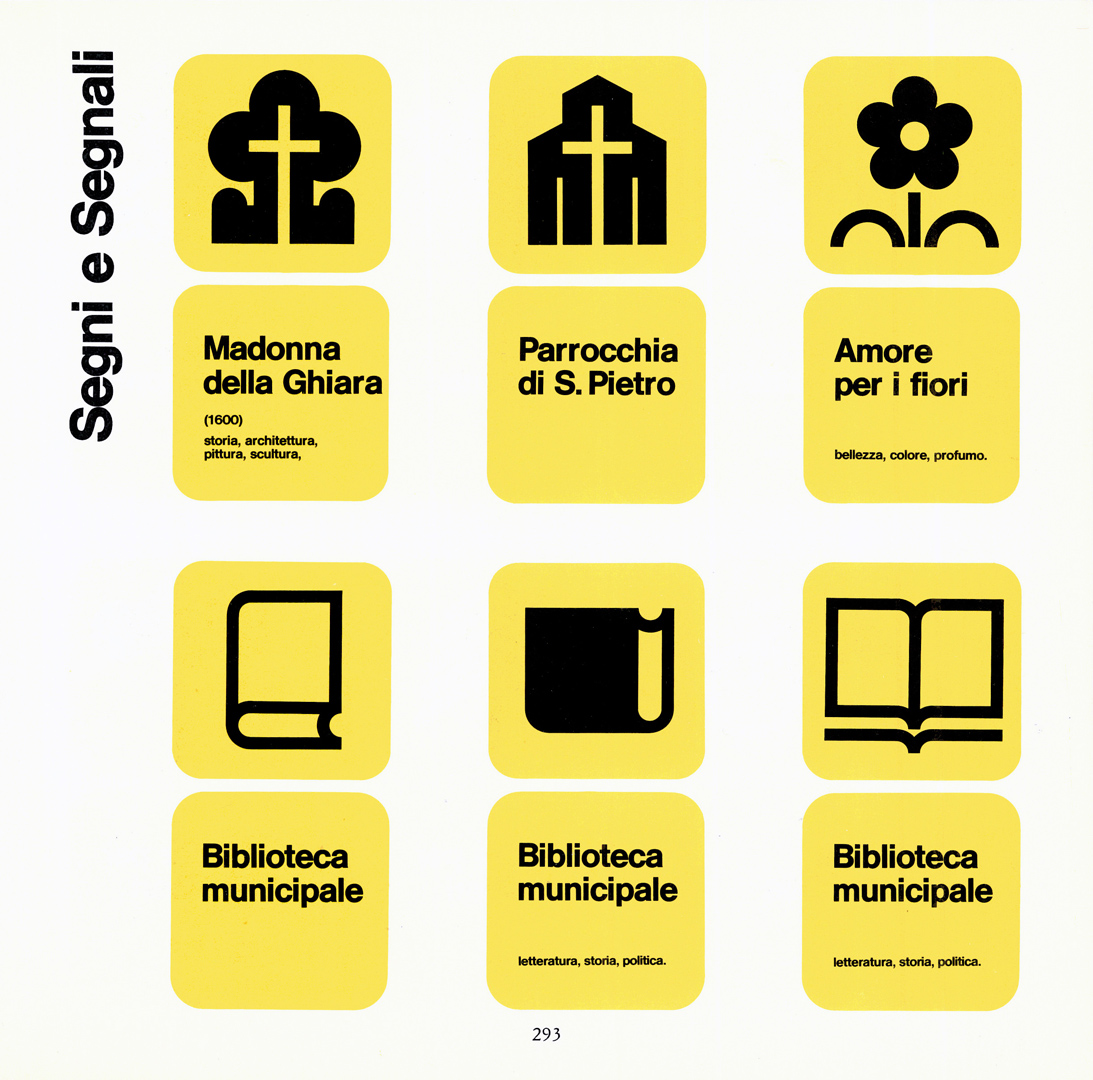

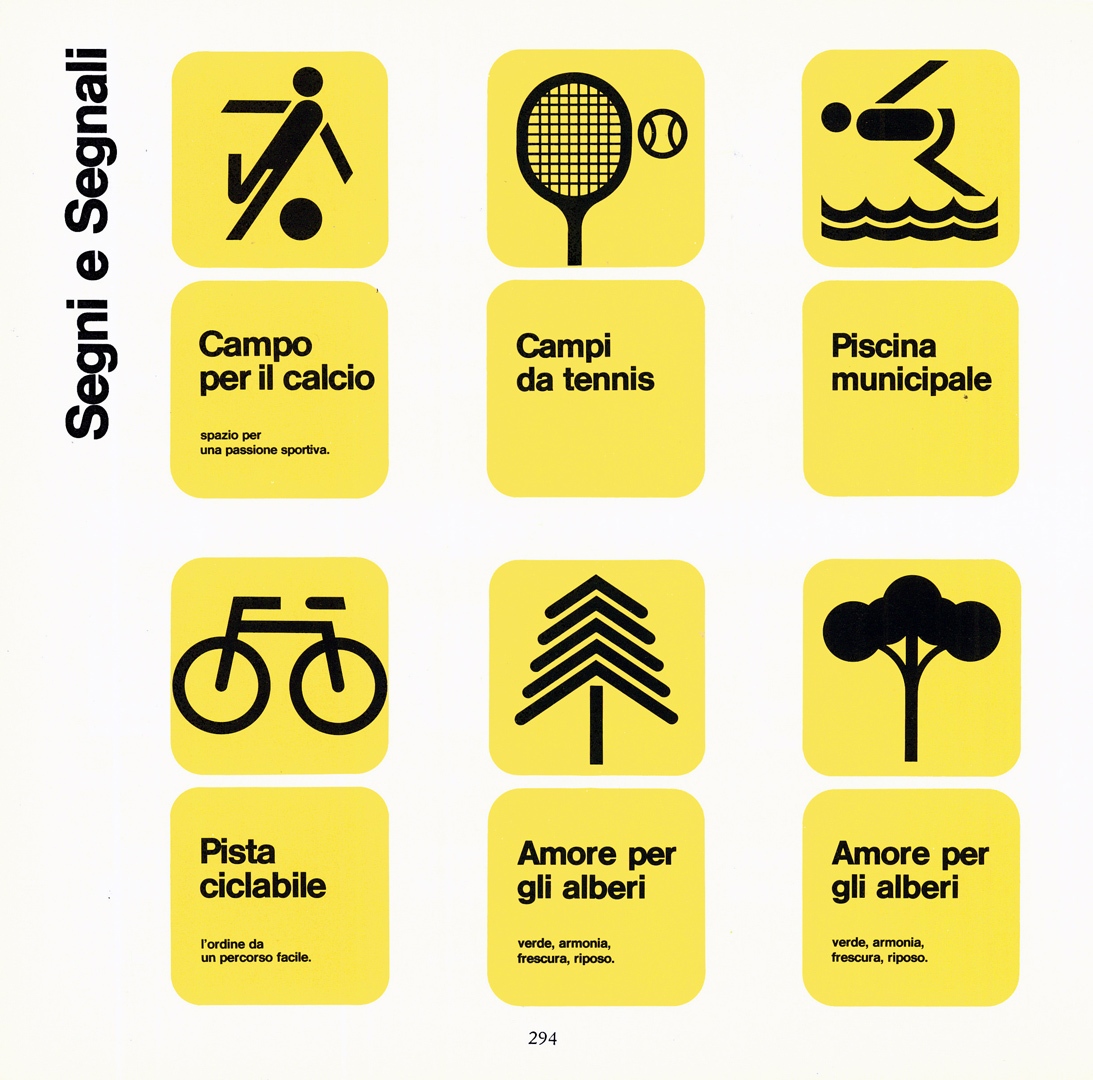

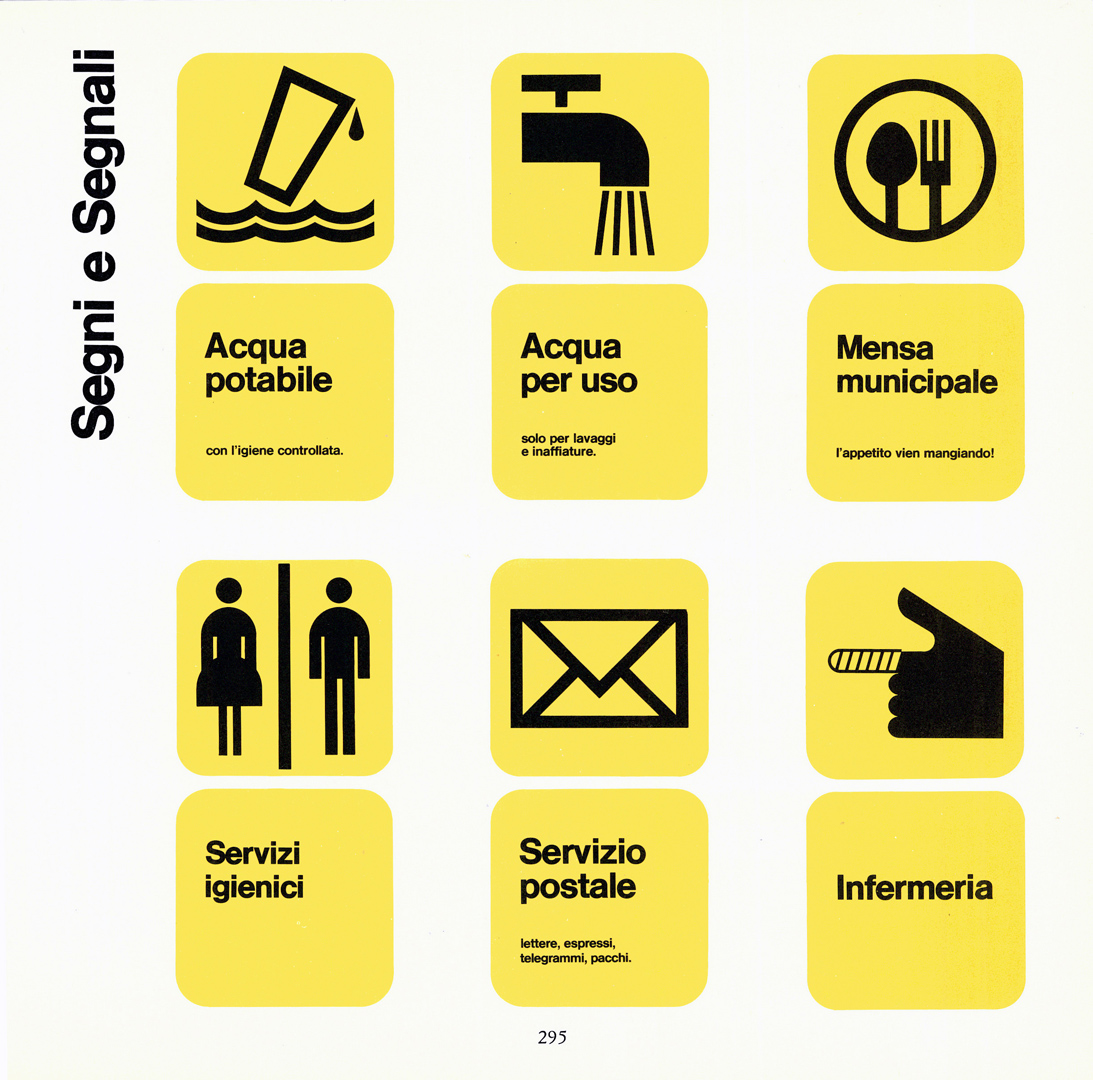

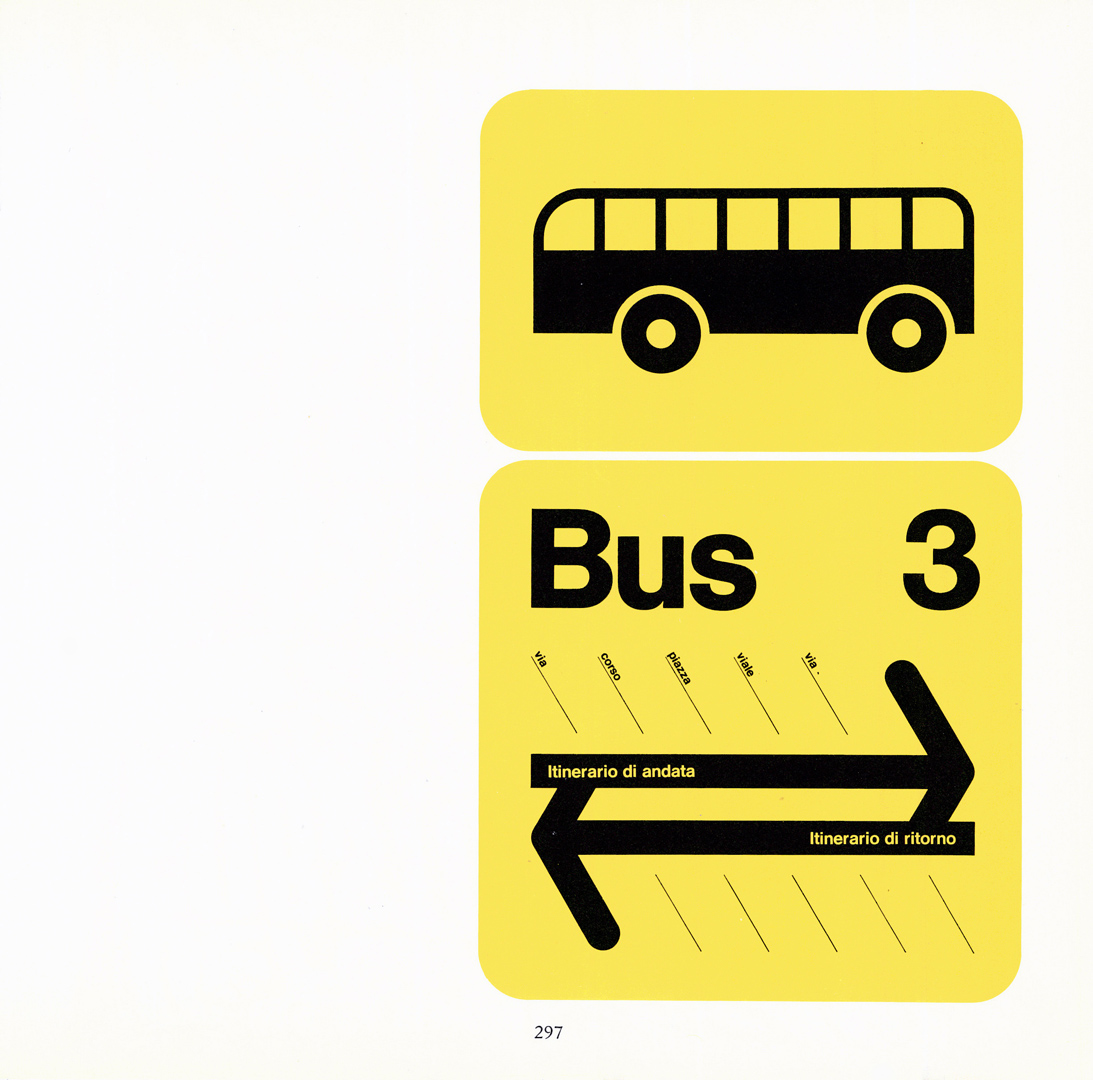

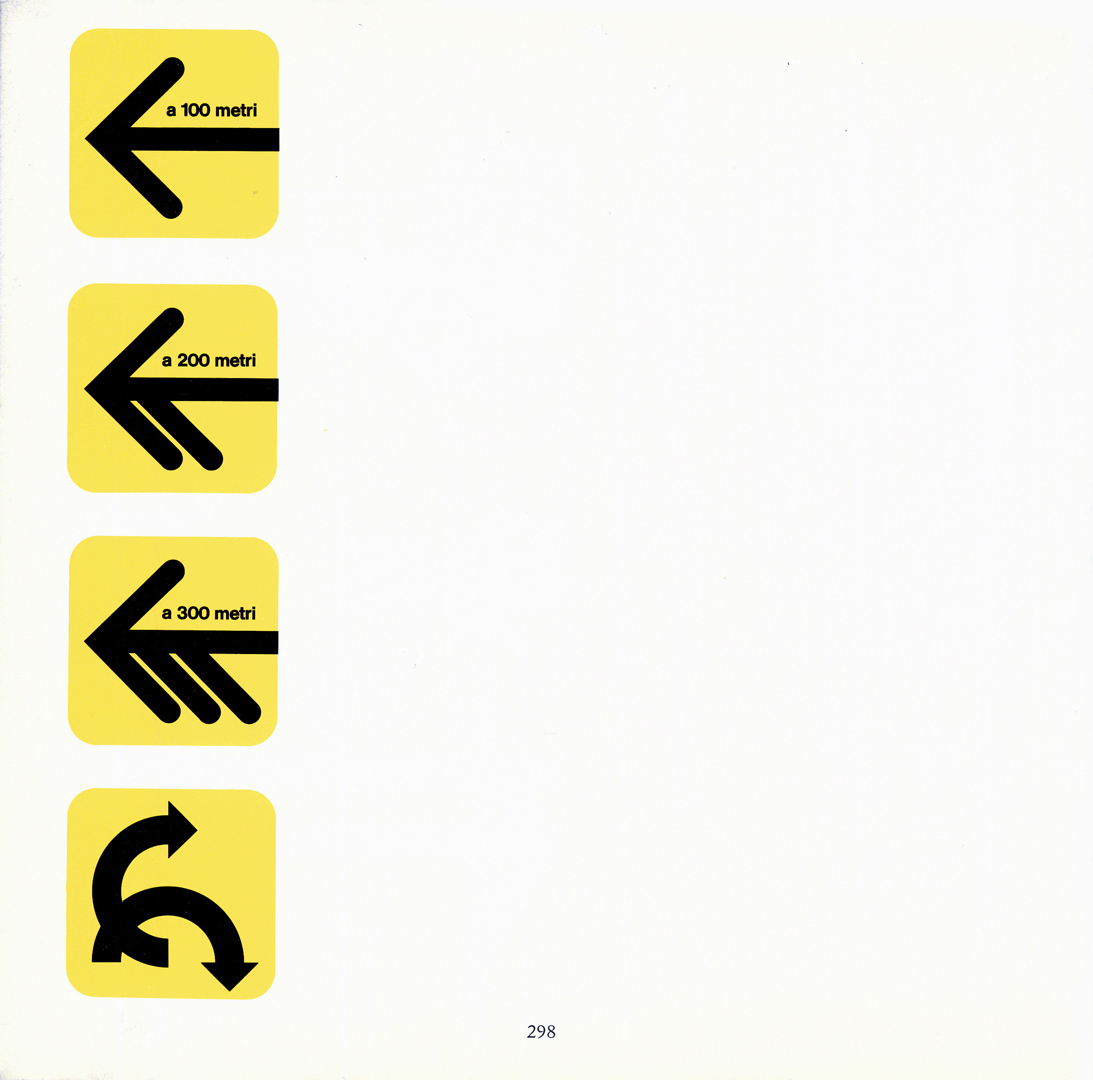

In this context, Franco Grignani’s 1981 project for a new signage system in the city of Reggio Emilia finds its place.

During that period, Grignani had already gained recognition in the city with a 1979 solo exhibition titled “Paintings, Experimentals and Graphic Design” at the Municipal Exhibition Hall:

In 1981, he also designed the logo for the Visual Communications Center of the city:

In the introduction that can be read in the book “La memoria della città” (“The Memory of the City”, interdisciplinary research on the historic centre of Reggio Emilia, with a preface by the famous semiotician Umberto Eco), Grignani conceives signage as a tool beyond mere communication, serving as an educational purpose while integrating seamlessly into the urban environment. His designs address both practical needs and the cultural identity of a place, balancing functionality with aesthetics. He emphasizes the importance of creating easily comprehensible symbols rooted in local heritage, reflecting elements such as architecture and art, and promoting a visual and environmental education that engages the community and enhances urban livability:

“It is evident that the city is already familiar with general traffic symbols (highways and national roads) but lacks sufficient knowledge of other signs.

[…] However, community cooperation is essential to help the city thrive in an environmentally organized system sustained by education.

[…] «Love for Plants» and «Love for Flowers» reflect a poetic expression of civilization that the municipality conveys to citizens, avoiding prohibitions and legal citations. Instead, these messages aim to educate people about the love of nature, encouraging the care and preservation of city gardens and parks.”

Grignani’s comment on the pedestrian crossing symbol stems from a personal experience: he was hit by a motorcyclist while crossing near his home:

“The symbol for pedestrian crossings depicts a couple walking briskly, accompanied by the phrase «Cheerfully in a hurry». This captures the entire problem, including its dramatic aspect, recalling pedestrians hit at crosswalks.”

This incident seems to have inspired his reflection on visual effectiveness:

“The area of pedestrian crossings raises issues of orientation and design rationality. Currently, in Italian cities, white stripes are placed along the axis of traffic, resulting in a distorted and reduced view for drivers, suggesting that these markings were designed more for pedestrians than for the vehicles causing harm. The new proposals involve “zigzag” lines with five movements, which form an arrow-like pattern (indicating pedestrians to the right). When seen from the perspective of traffic flow, they become highly visible as a warning.”

Grignani adopts a scientific and structured approach, focusing on vertical modular designs for readability, the use of durable and visible colours like warm yellow with black markings, and the inclusion of culturally meaningful symbols. The signs are adapted to diverse urban settings, from narrow streets to industrial zones, blending practicality with sensitivity to local conditions.

I still remember my grandfather asking me (I was only 10 years old) if his signals were understandable and what I thought they could mean…

[54] PCCC, courtesy of Paolo Credi

[all the other pics: courtesy of Daniela Grignani]

Last Updated on 20/02/2025 by Emiliano