What was a graphic designer like Franco Grignani doing collaborating with two nuclear scientists from Euratom?

Frequently, science and art are perceived as the ‘two cultures’ that seem to segregate our society into distinct factions. Nevertheless, certain pivotal aspects of both science and art share a common origin.

Here is another relatively lesser-known story.

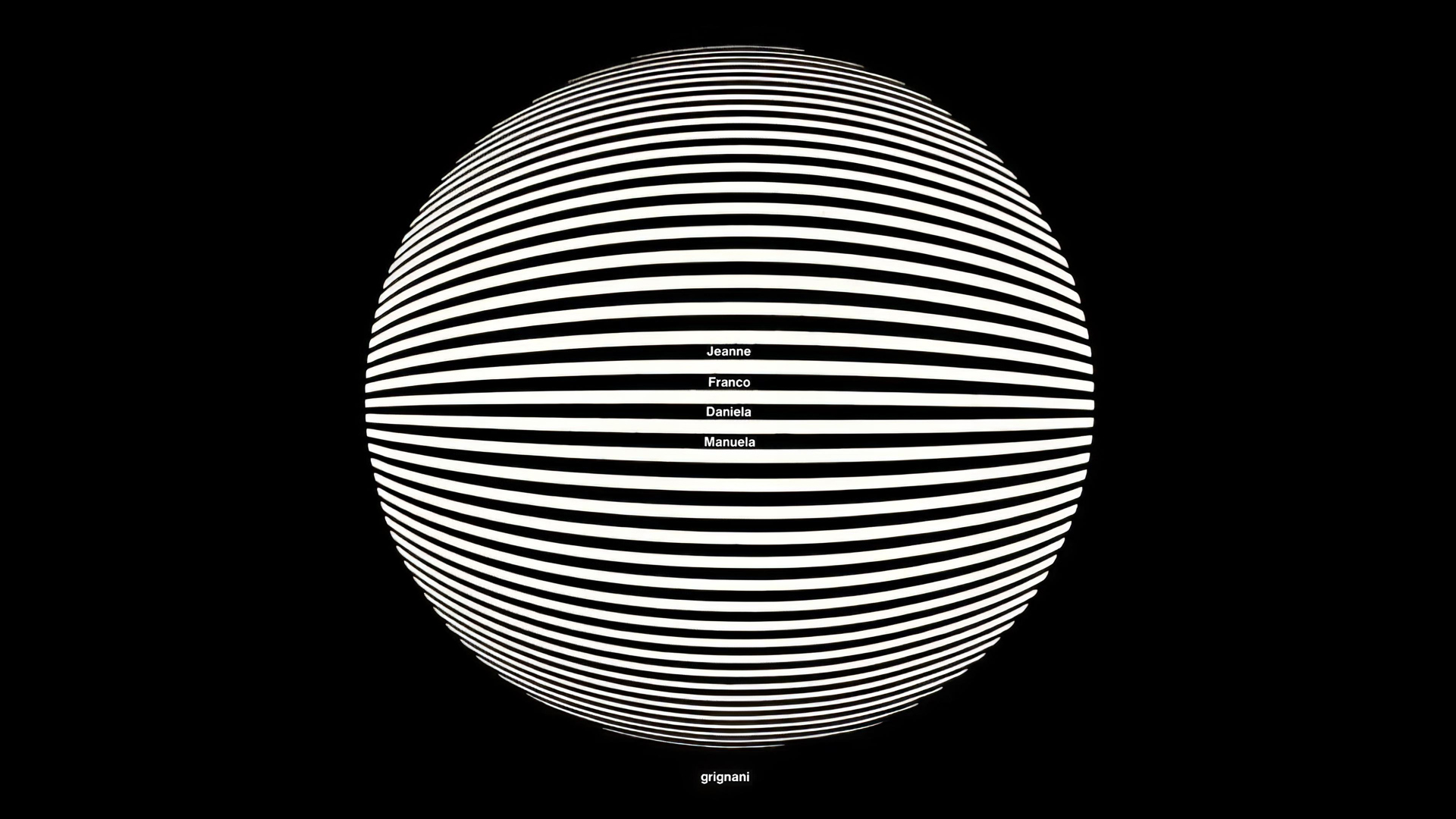

In 1975, a highly unique exhibition titled ‘Operativo 3‘ took place, initially at the ‘Marcon IV’ gallery in Rome and subsequently at the ‘Interart-Gallery’ in Milan. This exhibition was a collaborative endeavour involving Franco Grignani, Giancarlo Realini, and Flaviano Casali.

Giancarlo Realini, born in 1938, held the position of a physicist since 1968 on the faculty of the ‘Polytechnic School of Design’ in Milan (‘Scuola Politecnica di Design’), “committed to spreading the possibilities of application in the arts of the most recent technological discoveries” [from the catalogue of the exhibition] and, in collaboration with Flaviano Casali [as from the magazine ‘arte e società’, 2, 1975], served as a research scientist at Euratom (‘European Atomic Energy Community’).

Flaviano (Farfaletti) Casali was a mechanical engineer primarily involved in conceptual studies and design activities related to fusion reactors.

They both worked at the ‘Joint Research Centre’ located in Ispra, a town in northern Italy. This research center was established by the ‘Comitato Nazionale Energia Nucleare’ (CNEN – ‘National Nuclear Energy Committee’). Recently reached by phone (Oct. 2021), Realini confirmed to me that both he and Casali had a strong interest in art, but they needed an expert to provide guidance, and Bruno Munari referred them to Franco Grignani. Their collaboration with Grignani began in 1971.

The traveling exhibition in some ways echoed the objectives of the ‘Exhibition Design‘ group, of which both Grignani and Munari were a part from 1968 to 1976. This exhibition presented an “aesthetic research” that harnessed the latest advancements in technological progress, focusing on two main aspects referred to as “structural objectification” and “the limit as research”.

These two aspects, however, were rooted in distinct research foundations, given the different areas of expertise of Casali and Realini:

1. The “structural objectification”

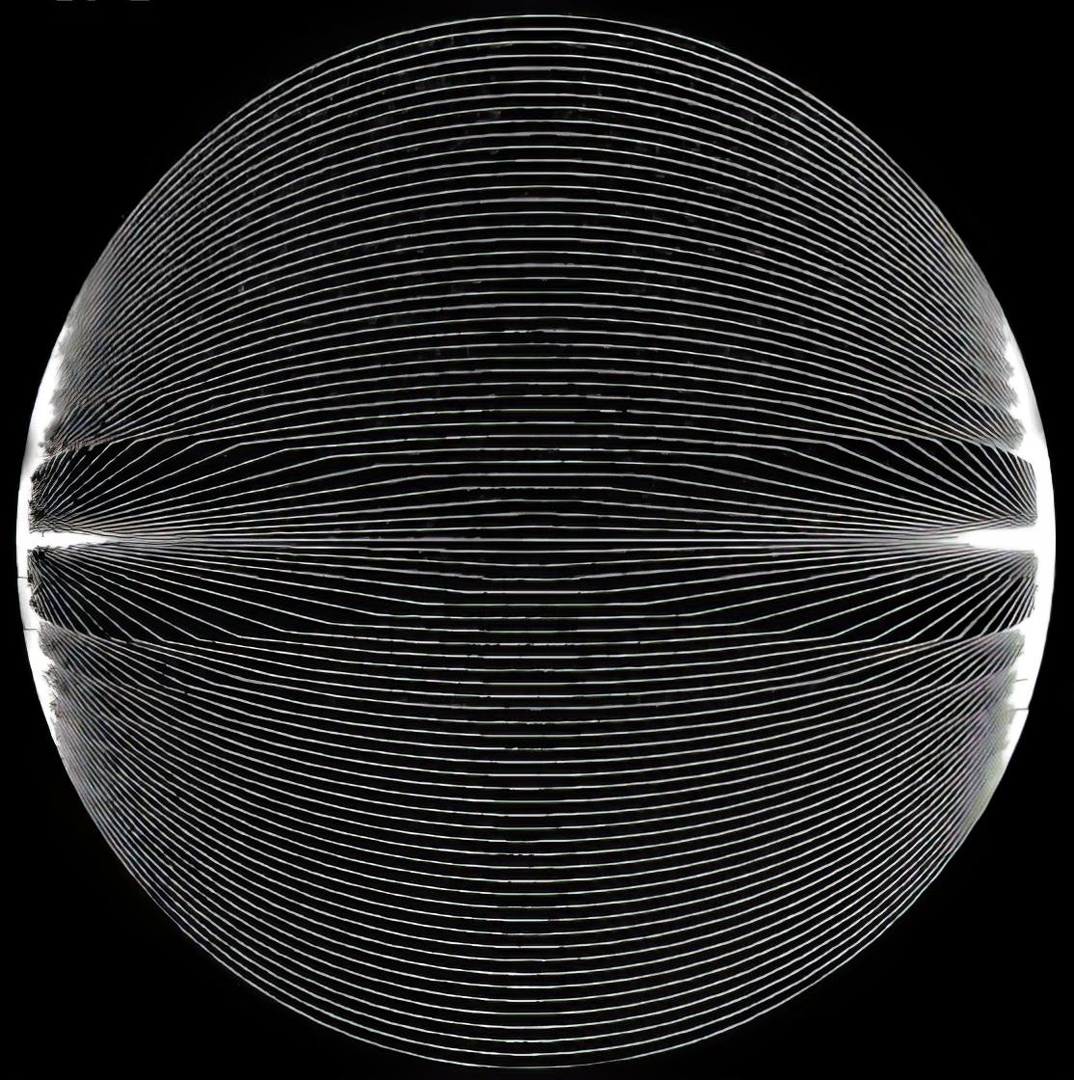

More precisely, “structural objectification” aimed to capture photographs of the internal strains within a material as it underwent mechanical stress, all without causing permanent destruction or deformation.

In the exhibition catalogue, the group stated that

“there has never been any interest, except in an intuitive way […], in what happens inside the structure itself […]. The intimate labour of a form, with its internal strains, torsions, frictions, etc. has never been analyzed. […] Multicolored lines of force develop and move at the slightest variation of the impulse that generates them.”

Although the Italian magazine ‘arte e società’ (issue n° 2, 1975) claimed an “authentic discovery”, it should be noted that such assertions were primarily limited to the artistic field. The theoretical study of strains in materials engineering had been known for some time, albeit within a relatively small circle of experts. However, there are situations where conventional analytical methods are not effective. Under the guidance of Flaviano Casali, the group applied, for the first time for aesthetic purposes (although some early experiments had already been conducted by Bruno Munari in the 1950s), the techniques of ‘photoelasticity‘ (first applied in Italy in 1909). This method involves visualizating internal strains in a structure by subjecting a birefringent material under stress (in the case of the ‘Operativo 3‘ group, epoxy resin) using a beam of polarized light. Before the advent of more advanced computer processing, no other method provided the same visually compelling stress pattern.

The research took “about two years” (as from ‘arte e società’, 2, 1975), in part because of the limited availability of experimental materials in the Italian market, mainly relying on large Polaroid plates imported from England.

Franco Grignani had previously employed industrial glasses, oils, and deforming liquids in his photographic work. The images produced by the ‘Operativo 3‘ group, in some ways, bear a resemblance to his earlier photographic experiments.

2. “The limit as research”

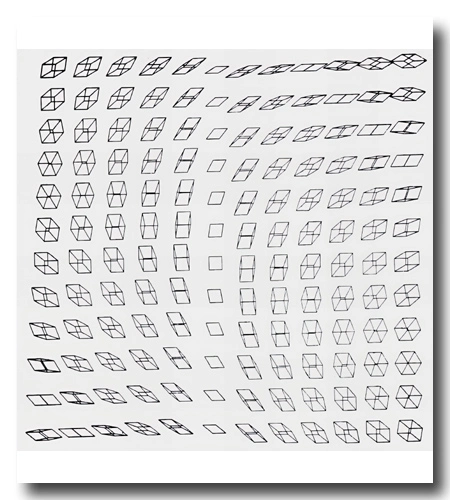

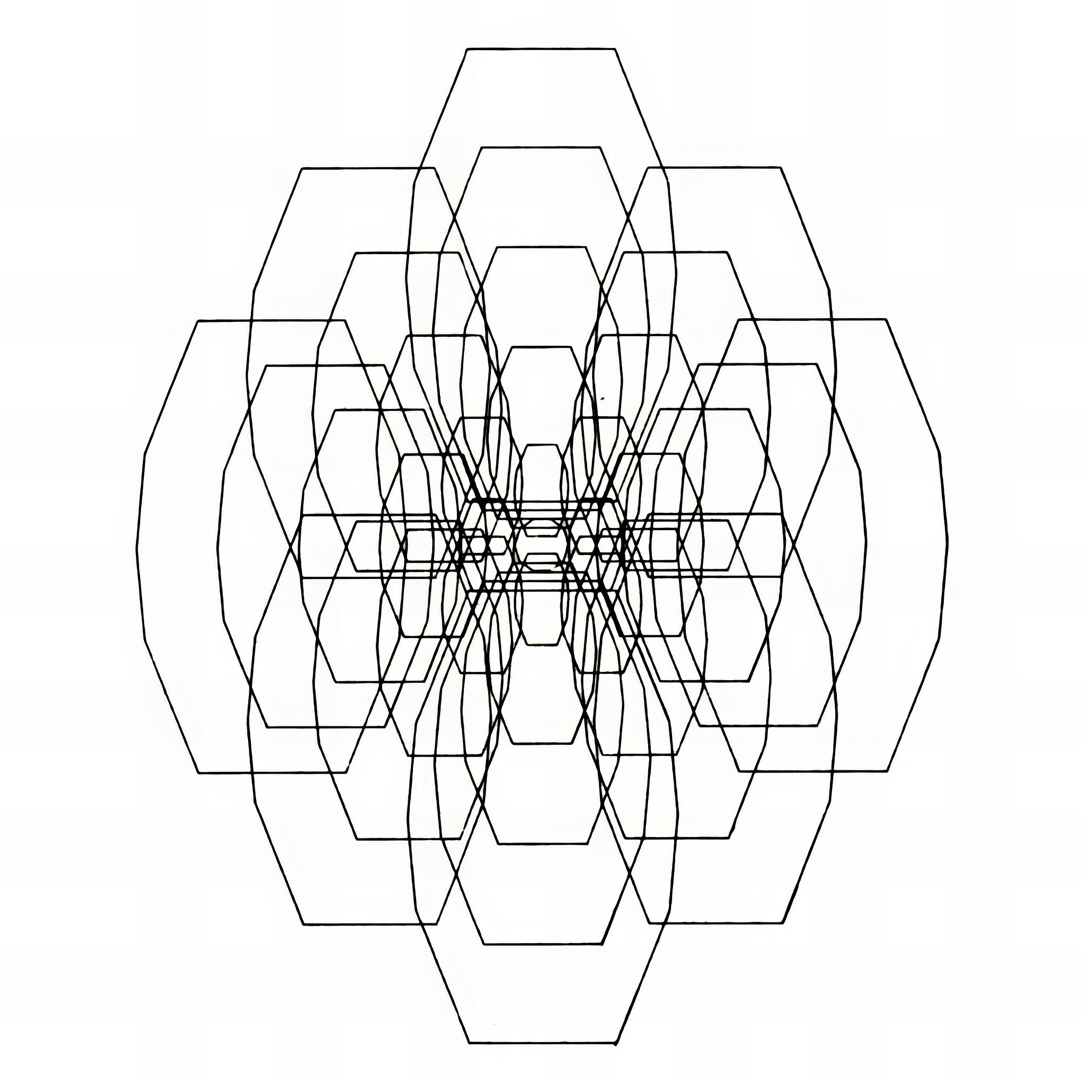

“The limit as research” was the second crucial aspect of the ‘Operativo 3‘ group’s exhibition. Under the guidance of Giancarlo Realini, the group aimed to utilize recent advancements in the field of electronic elaborators for aesthetic purposes. It’s worth noting that the term ‘computer graphics’, coined by Boeing in 1960, didn’t gain widespread use in Italy until more than two decades later.

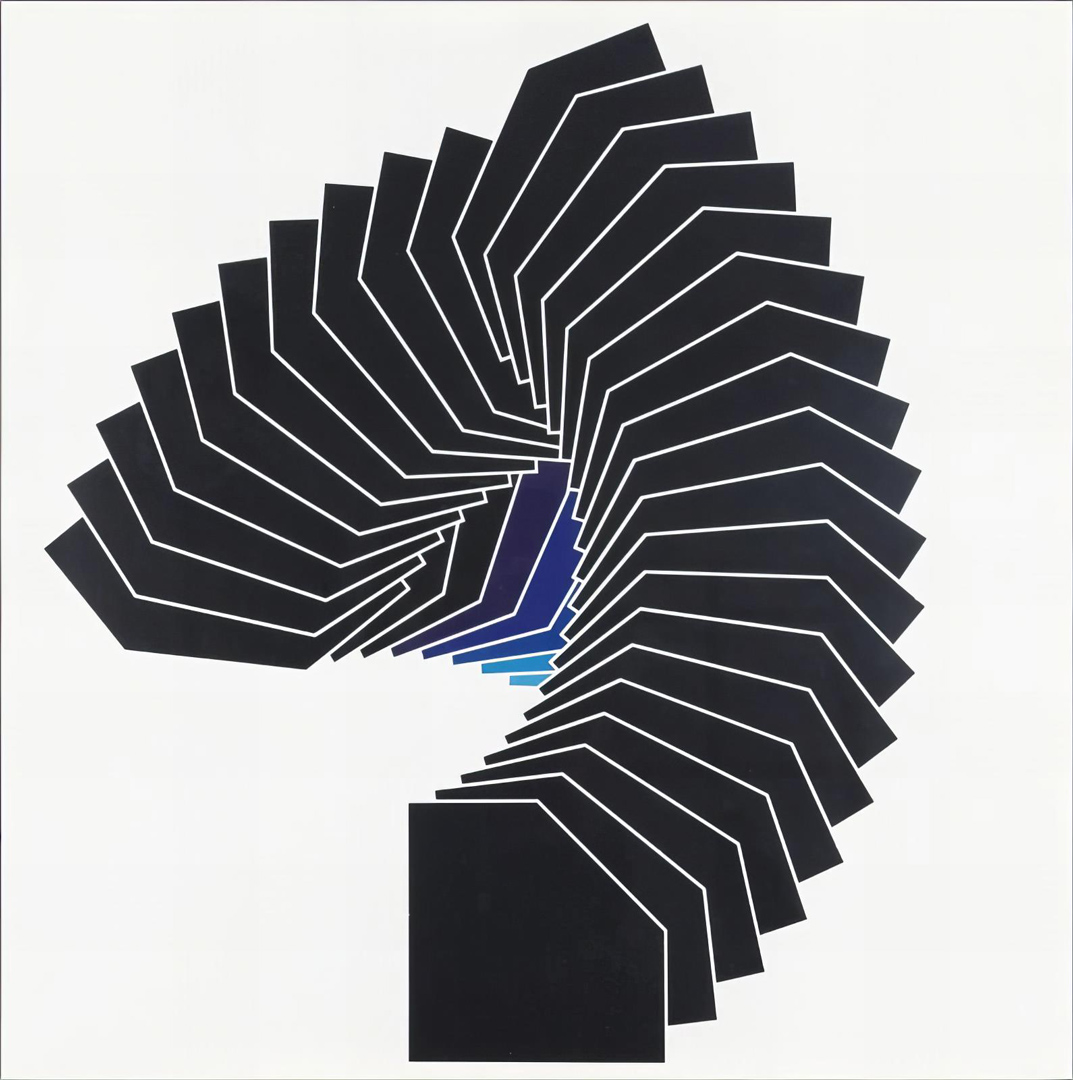

While it might come as a surprise that Franco Grignani, known for creating highly complex geometric images solely through his manual abilities, ventured into the realm of computers (it is still believed – erroneously – that he was somewhat ‘allergic’ to the use of electronic technology), his early fascination with Futurism, particularly concepts like speed and dynamism rooted in the celebration of mechanical progress, couldn’t leave him untouched. As electronic technology evolved in the 1970s, it naturally caught his attention.

Even though the most computer-like tool he had at home was his Olivetti Lexikon 80 typewriter, it’s important to note that in 1981, Cesare Musatti, who introduced the Psychology of Gestalt to Italy, stated in an exhibition catalogue from ‘Lorenzelli Arte’ that in Grignani’s artworks “everything is calculated, everything is precise: and it is a work that could be the result of a well-prepared elaboration conducted by an electronic computer.”

The group ‘Operativo 3‘ stated in the exhibition catalogue that

“one cannot deny the possibility of stimulation that the computers can exercise on an attentive and sensitive operator. This is realized in the close dialogue that is established between man and machine through the enormous amount of detailed and overall images that can be requested from the computers.”

Of course, at that time there were strong limits: computers were mainly used by large industries, laboratories and universities and “the reasons why not many results have so far been achieved without an immediate utilitarian purpose are to be found in the high cost of using the computers and in the technical difficulties encountered. In fact, those who would have something to say from the aesthetic point of view, are not familiar with the language of programming” [from ‘Linea Grafica’, issue n° 3, 1972], a situation that confined the use of computers still at the boundaries of artistic experimentation (the first Apple Macintosh launched onto the market is from 1984).

For the works realized within the ‘Operativo 3‘ group, Giancarlo Realini had the chance to trust upon an IBM 7090 supplied to Euratom in Ispra since 1961, a powerful data processing system occupying an area of c.ca 500 square meters; sold in 1960 for $2.9 million (equivalent to $20 million in 2020) and used by NASA to control the Mercury and Gemini space flights, it was defined in 1966 in Italy as a calculator that “makes possible the impossible”. At that ‘epic’ time, the results of computer processing could be displayed exclusively using plotter printing [from a personal interview with Realini in Oct. 2021].

Professor Maddalena Dalla Mura from the IUAV in Venice recently (2016) examined the reception of computers and the digital revolution in Italy through the articles that appeared in the magazine ‘Linea grafica’ in the period 1970-2000, and reported how “the great changes that then [the mid-1970s, Ed.] worried the world of typography, such as photocomposition and the increasingly widespread application of the computers, seemed to have little interest within the so-called ‘creatives’.”

Franco Grignani was an exception (he had at home a copy of “Computer Graphics – Computer Art” by Herbert W. Franke, 1971), and in the exhibition catalogue of ‘Operativo 3‘ and later (1976) in an article in the magazine ‘Rivista IBM’, he was presented as follows:

“An observer of the changing realities that the event of technologies bring into man’s life and conscious of the rights of independence and creativity of the human mind, he proposes to the computer (the machine) the mockery of mathematical absurdity or the conceptual trauma of affirmation and negation in order to counterpose the triumph of the imagination and the consciousness of the inner infinity to the terrible speed of calculation.”

The research of the group ‘Operativo 3‘ ranged from the generation of complex structures by combining simple geometric figures, to the combination of deformations through rotating movements and many other graphic experiments which were later exhibited (1977) or published (1983) by Realini, who continued to produce further studies independently in the following years.

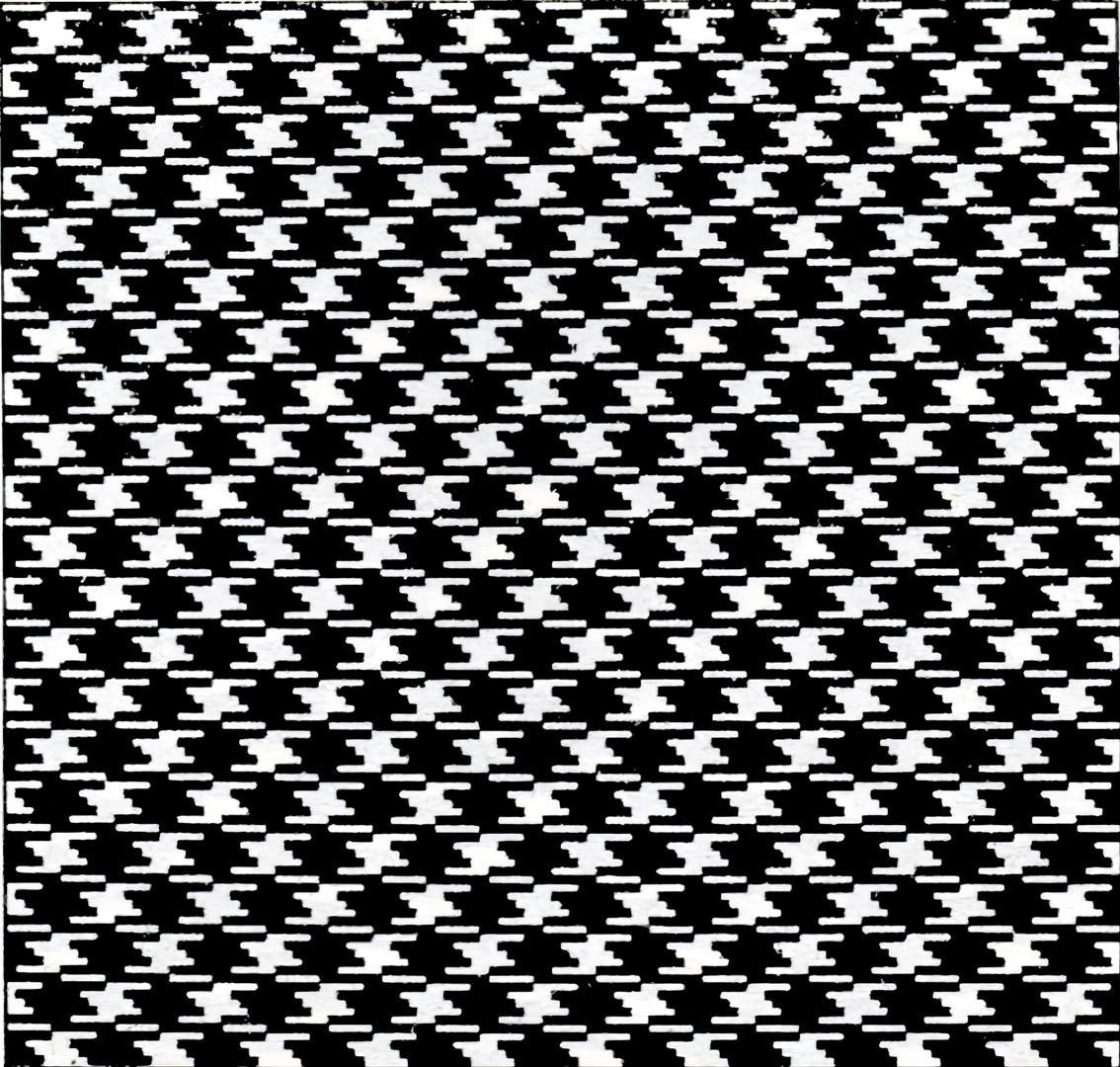

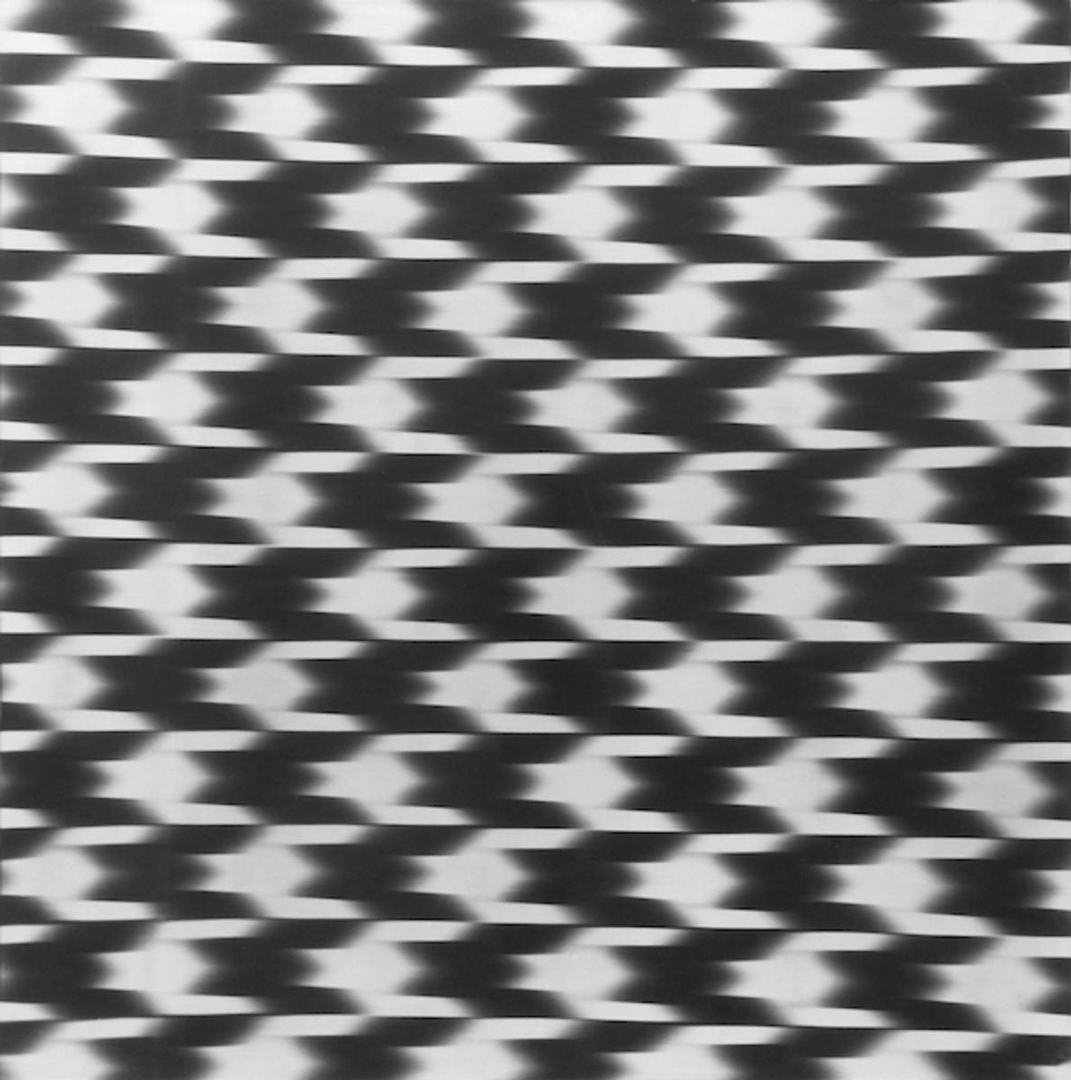

Again, we can find – as always in Grignani’s work – some similarities with earlier ‘hand-made’ works:

The exhibition catalogue concluded:

“Different researches as theme and visual result, but always aimed at an almost exasperated use of the machine and the tools of realization, in search of their limits.”

That’s a charming anecdote about the exhibition, recalled by Realini: Realini, Casali and Grignani were answering some questions about their work, Realini and Casali talking and talking… while Grignani kept in his silence; so, someone in the audience asked him: «But, Architect, do you have anything to say?» – «Me? I work». And that was all. That was my grandpa, he managed to be incisive with just a couple of words and silence the entire audience.

However, the magazine ‘arte e società’ (issue n° 2, 1975) underlined how art critics were unprepared for this kind of exhibition, unlike the public, which proved instead to be “attentive and demanding”.

Later recalling these experiences, Realini wrote in 1983: “A few years ago, when for the first time these works went out of the narrow circle of the insiders and were exposed to the public also with specific exhibitions, some were tempted to consider them as the expression of a ‘new art’. In our opinion, it would be more correct to say that a new working technique was being revealed which, economic matters aside, even artists could access. In fact, the works displayed, even if made by technicians not particularly interested in an ‘aesthetic’ discourse, had to have a value of stimulus, of novelty for the real aesthetic operators, who, we will never tire of saying, must intervene on that fact of historical importance represented by the widespread diffusion of electronic processors” [from Giancarlo Realini, “Disegnare col Computer”, 1983].

Lacking adequate recognition by art critics, unfortunately, the group ‘Operativo 3‘ disbanded shortly after the first two exhibitions in 1975. However, Giancarlo Realini continued to exhibit some further results at the ‘Galleria San Fedele’ in Milan, in February 1977. The birth of the computer “is very recent,” wrote Realini in this exhibition’s catalogue, “its penetration throughout the world very rapid: so rapid that we have not yet realized how much the computers have become necessary for our lives […] it is certain that their use will be increasing more and more.”

Giancarlo Realini has certainly been a forerunner of Computer Graphics in Italy, but abroad developments in the field were progressing faster. By 1985, the Italian magazine ‘Linea grafica’ stated that “it still remains to be understood how graphic designers will use all the features of these new techniques”. However, in 1973, Melvin Lewis Prueitt, a staff scientist from Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, was already creating 7-colour 3D computer graphics: all those who were young in Italy in 1981 can remember the beautiful animated computer graphics theme of the television show ‘Quark’ that he was commissioned, slightly anticipating the far more complex computer-generated polygonal animation seen in the cult movie ‘Tron‘ (1982, incidentally a financial failure for Disney at the time).

The collaboration with the two scientists was not an isolated one: in the same year 1975, Professor Giuseppe Caglioti, a professor of Nuclear Science born in 1931, first encountered Franco Grignani at the anthological exhibition “Franco Grignani. A Methodology of Vision” at the ‘Rotonda della Besana’ in Milan. Facing Grignani’s artworks, Professor Caglioti was deeply fascinated and experienced a sort of Stendhal syndrome [as declared in 2018]. He was struck by the “disconcerting analogy between the process of spectroscopic measurement of quantum structures and the dynamic perception of ambiguous images”.

Many years later (2013), Professor Caglioti recalled a conversation he had with Grignani during that encounter:

«Maestro – I ask him – how come the quantum spectroscopy measurements that we physicists make in the laboratory, on which our scientific certainties are based and on which the concrete developments of new technologies are founded, resemble in such an evident way the optical illusions that I feel at the moment of the perception of these undecidable, ambiguous, absurd, inconcretizable structures of yours?» He replies: «These works are not meant to be observed by easily impressionable people. Also, why inconcretizables? Go ahead and touch them, professor!» I remained deeply disturbed. The reassuring certainties of laboratory life were melting like snow in the sun. The visit to that exhibition triggered anguished questions about the foundations of scientific problems in which I was engaging. […] Nights full of nightmares followed. There was only one way out: study the problem, trusting in the help of the person who had unwittingly raised it.

During a recent phone conversation in September 2021, Professor Caglioti shared with me his recollection of how he first learned about the exhibition, which had taken place a few months prior to ‘Operativo 3‘. His colleagues Giancarlo Realini and Flaviano Farfaletti-Casali had recommended the exhibition to him, leading to his attendance.

This encounter marked the beginning of a profound collaboration between Grignani and Caglioti that extended over several years. Their collaboration resulted in jointly agreed artworks and a co-authored publication in 1983 titled “Simmetrie infrante” (“The Dynamics of Ambiguity”), featuring a cover designed by Grignani. Within this book, Professor Caglioti explored the concept of broken symmetries, drawing parallels between the creative processes of art and scientific theory. He also highlighted the similarities between the processes of perception and measurement.

Professor Giuseppe Caglioti continues to be actively involved in promoting, especially for educational purposes, the potential for aesthetic interpretation of certain intricate aspects of quantum mechanics. He consistently references the work of Franco Grignani in this context (see: ‘Scienza in rete‘).

“People think that men of science are there to educate you, and poets, musicians, etc., to cheer you up. That the latter have something to teach does not occur to them.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein, quoted by Giuseppe Caglioti, 2013

[special acknowledgement to Professor Maddalena Dalla Mura from the IUAV in Venice, for helping me examine issue n° 3 of ‘Linea Grafica’, 1972]

[*] courtesy of Daniela Grignani

[a] & featured pic (1973): ‘Operativo 3’, Marcon IV Gallery, Rome, exhibition catalogue, 1975

[b] ‘Rivista IBM’, supplement to issue n° 4, 1976, curated by Herbert W. Franke

[c] Giancarlo Realini, Galleria San Fedele, Milan, exhibition catalogue, 1977

[d] Giancarlo Realini, “Disegnare col Computer”, 1983, courtesy of Giancarlo Realini

[7] AIAP / CDPG Centro di Documentazione sul Progetto Grafico, courtesy of Lorenzo Grazzani

[25] Il Post & M&L FINE ART, courtesy of Matteo Lampertico

[32] Lorenzelli arte, courtesy of Matteo Lorenzelli

[35] Design is fine, courtesy of Andrea Riegel

Last Updated on 13/04/2025 by Emiliano