Based on one article published in Time magazine on October 23, 1964 (‘Op Art: Pictures that Attack the Eye‘), the term Optical Art, or Op Art, emerged in the early 1960s as a branch of geometric abstract art focusing on optical illusions and visual perception. Op Art was an inherently interdisciplinary movement, intersecting with fields such as psychology, science, mathematics, and physiology.

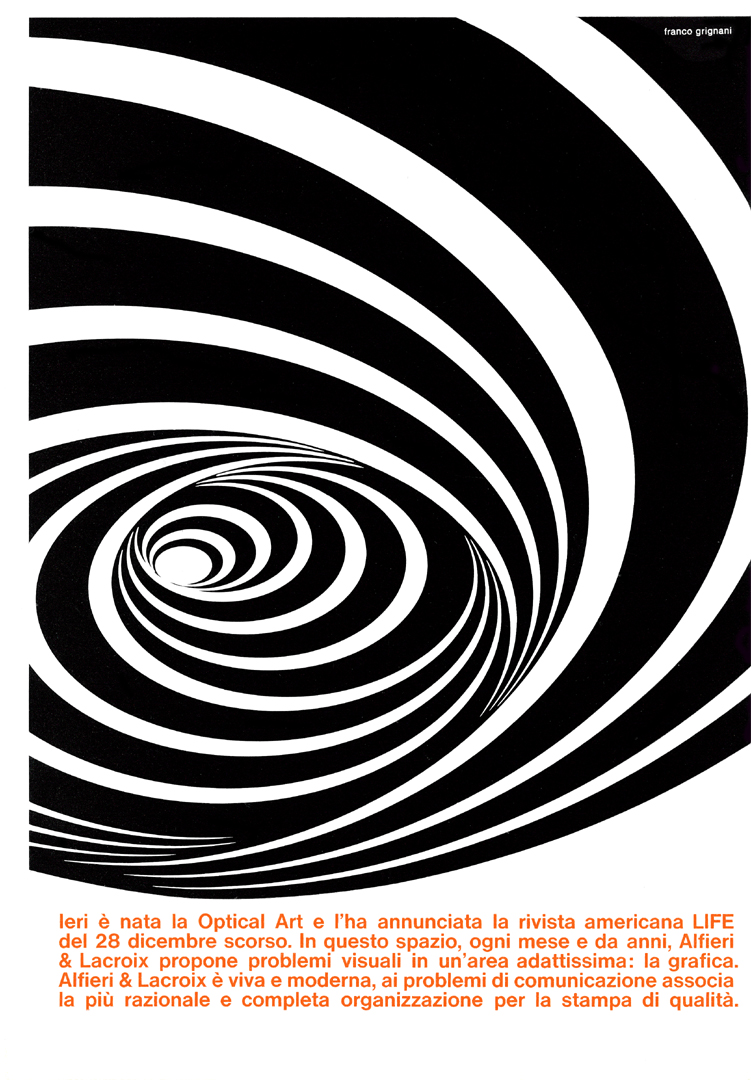

Life magazine also featured an article on Op Art in December 1964, which Franco Grignani wanted to quote in this ad for Alfieri & Lacroix:

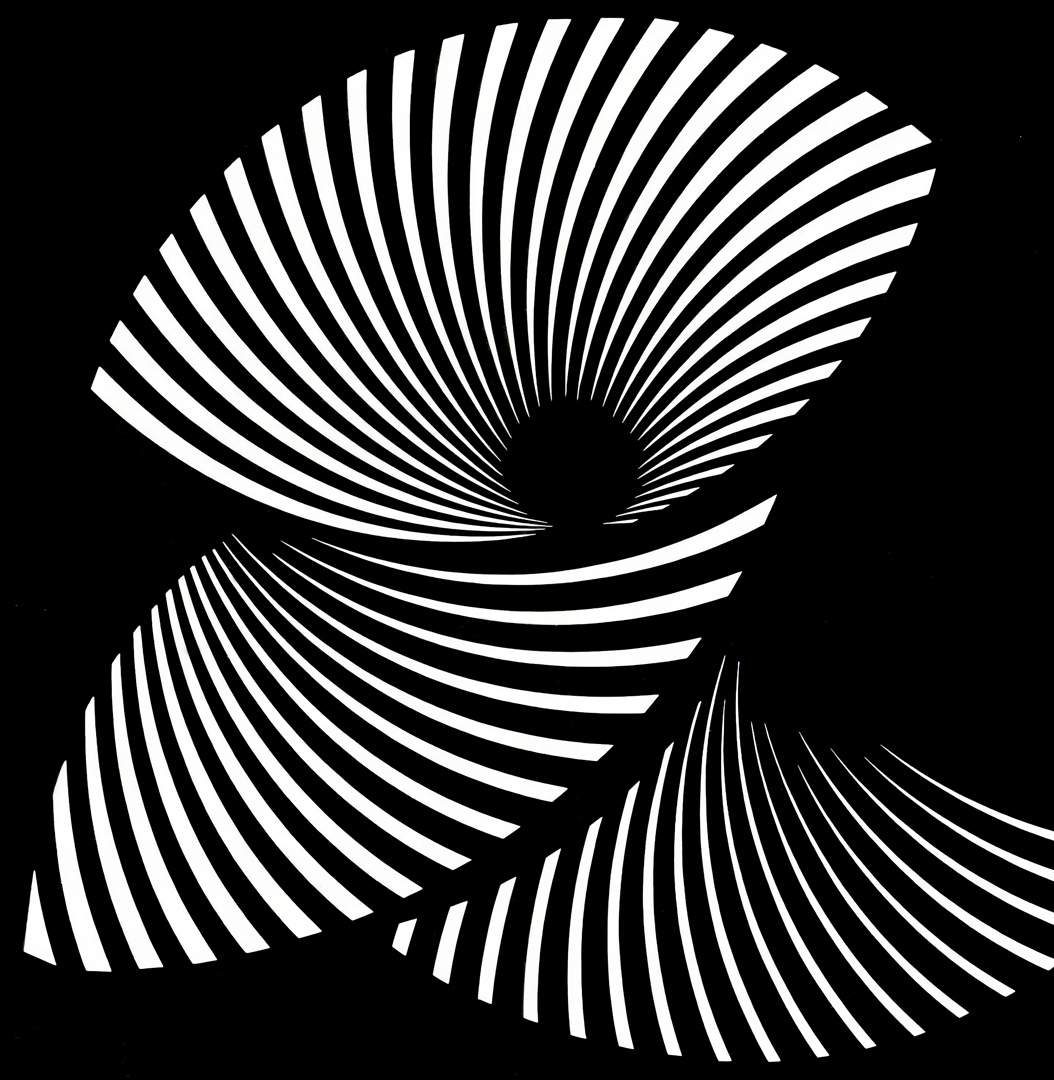

Franco Grignani, renowned for his pioneering work in graphic design and optical illusions, had been exploring the potential of geometry and visual contrasts to create effects of movement and dynamism since the 1930s and 1940s. Although Grignani was not officially associated with the Op Art movement, his paintings from as early as the 1950s anticipated its visual language. These works presented perceptually challenging arrangements of lines and shapes that appeared kinetic after prolonged observation.

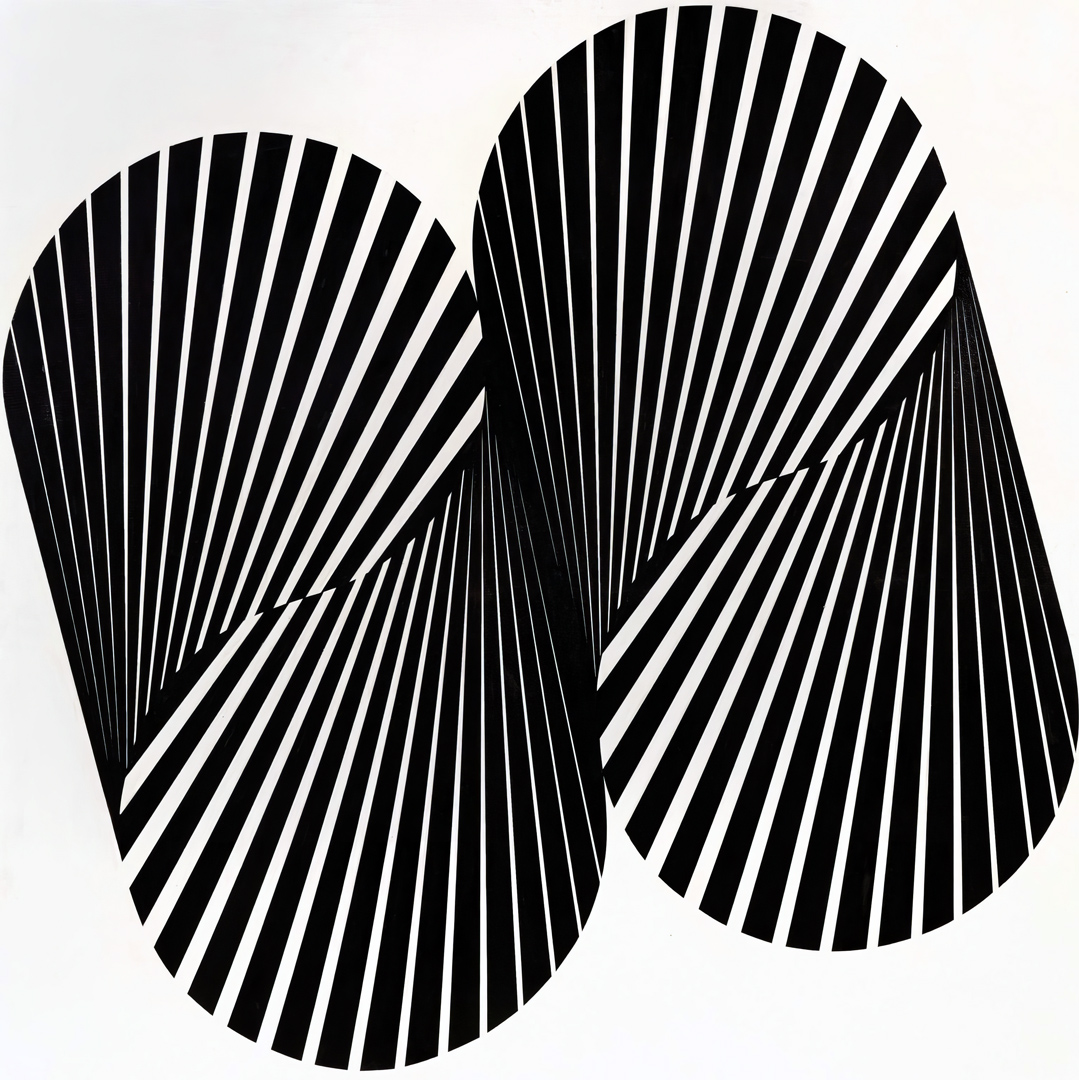

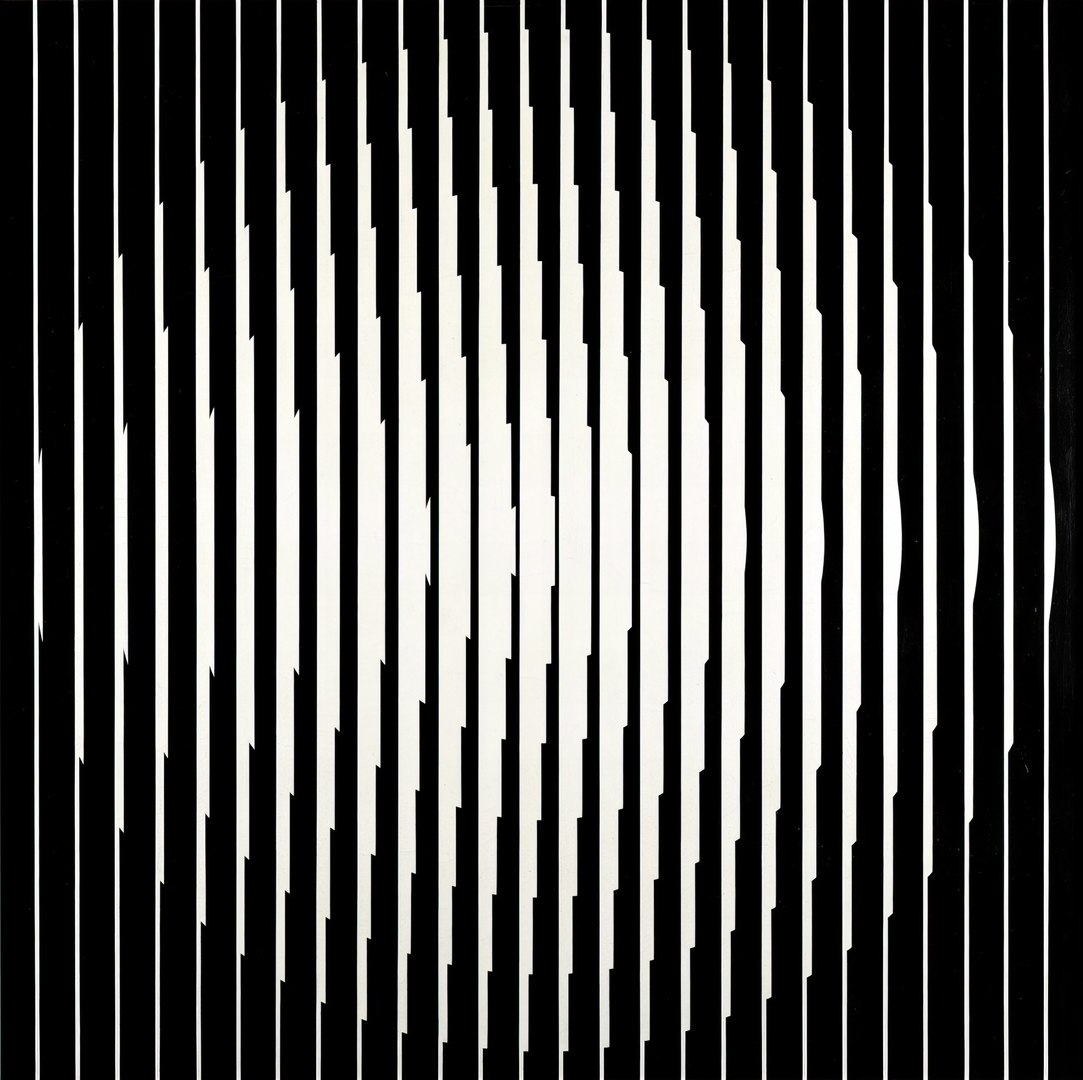

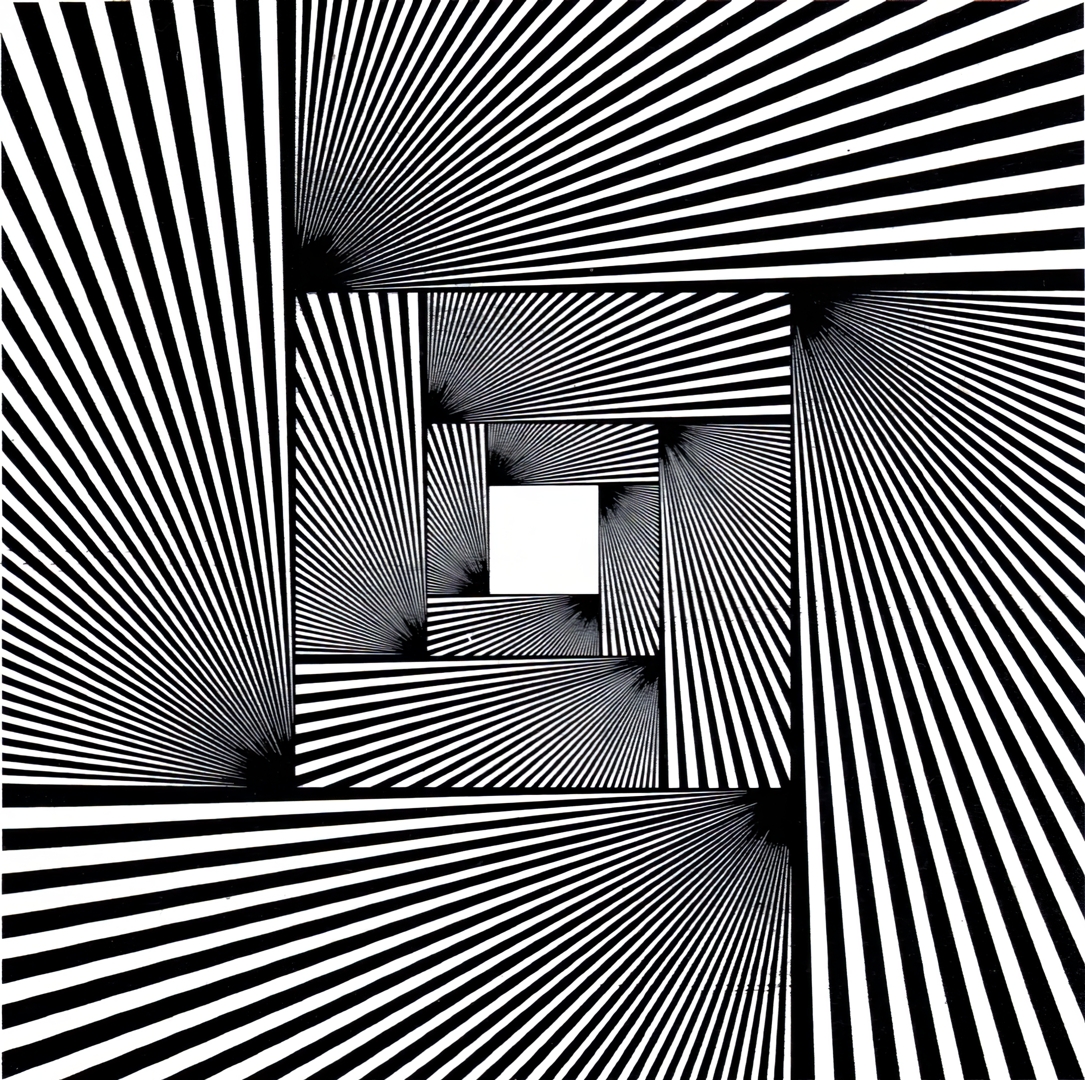

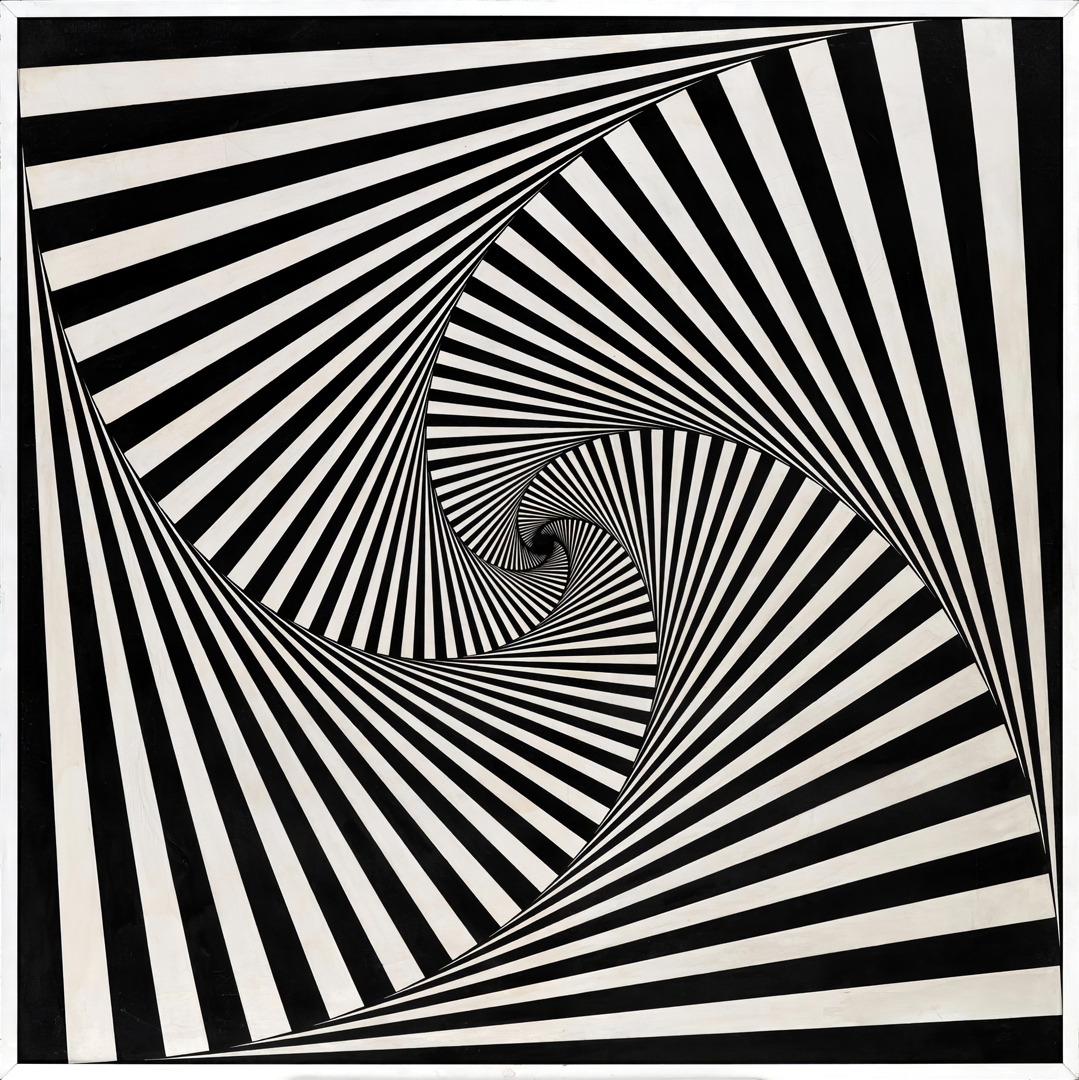

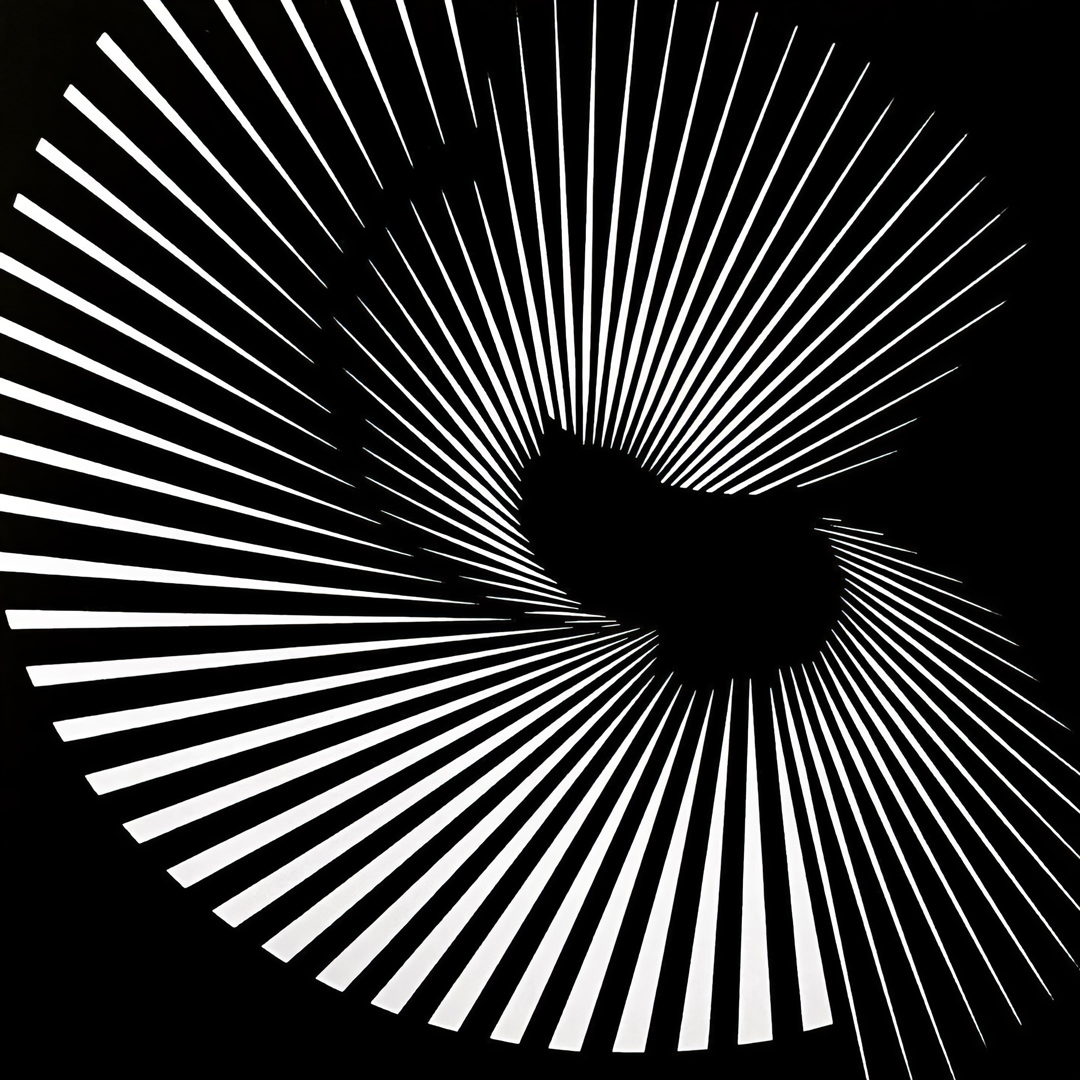

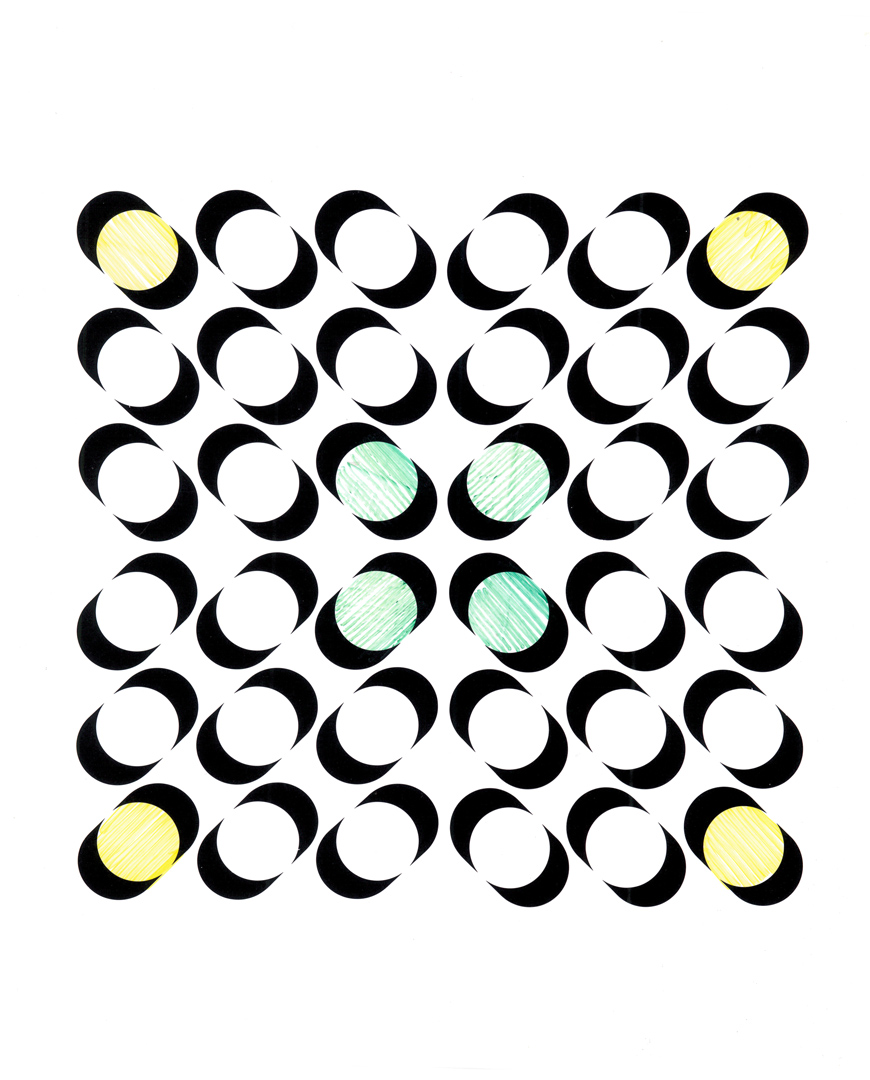

Despite producing such works well before the widely recognized Op Art pioneers like Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley, Grignani was notably absent from The Responsive Eye exhibition at MoMA in 1965, which is credited with bringing Op Art to mainstream attention. However, MoMA does own one of Grignani’s works: a lithograph donated by the artist himself, dated 1965, the same year as the exhibition. This piece would have seamlessly aligned with the themes and aesthetics of The Responsive Eye:

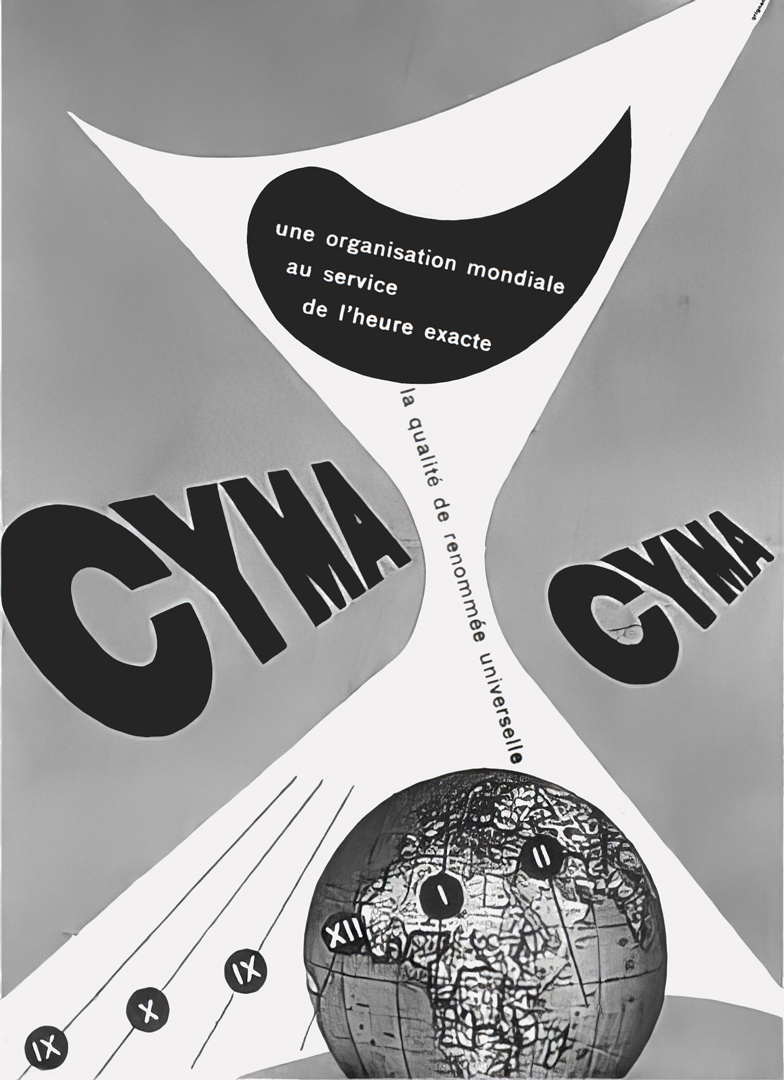

Interestingly, Grignani had been featured in an earlier MoMA exhibition, Modern Art in Your Life, in 1949. His contribution to that show was not a painting but an advertisement – yet it too would have fit perfectly within the framework of The Responsive Eye:

“[free form] can serve to attract the eye to whatever it encloses. Designers use to make lettering stand out (advertisement for Cyma watches) […] [these] are special applications of a new but now generally accepted style.“

[from the catalogue of ‘Modern Art in Your Life‘, 1949]

This early recognition of his work highlights Grignani’s forward-thinking approach and his undeniable influence on the Op Art movement.

The Op Art style extended beyond art galleries, deeply influencing also mid-1960s fashion, which was already breaking from tradition amid the cultural dynamism of the youth revolution. The fusion of Op Art and fashion not only redefined 1960s aesthetics but also paved the way for future artist-designer collaborations. Its striking visuals and ability to manipulate perception made it ideal for textiles, aligning perfectly with fashion’s push toward modernity and new forms of expression.

“In Tokyo this year, an element taken from one of my covers for Graphis 1963 was used in the invitation to a high fashion show.” [I]

[Franco Grignani, from the Italian-French magazine ‘arte e società’, 6/7, 1973]

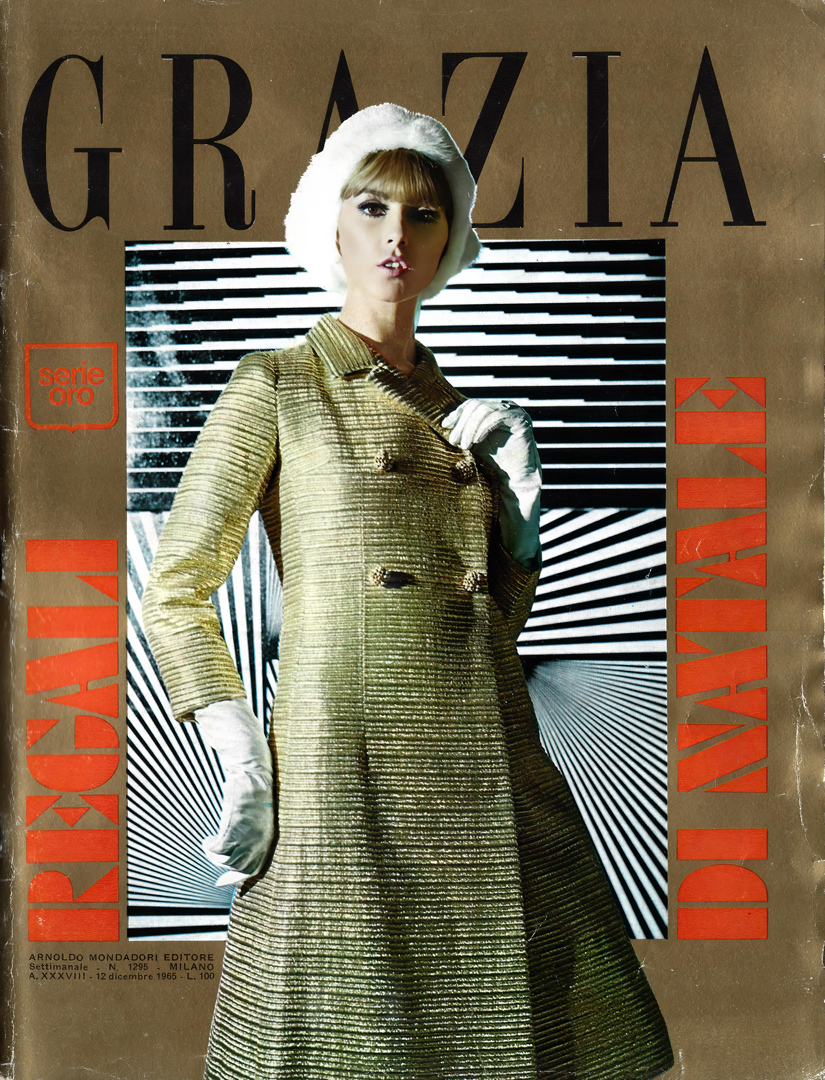

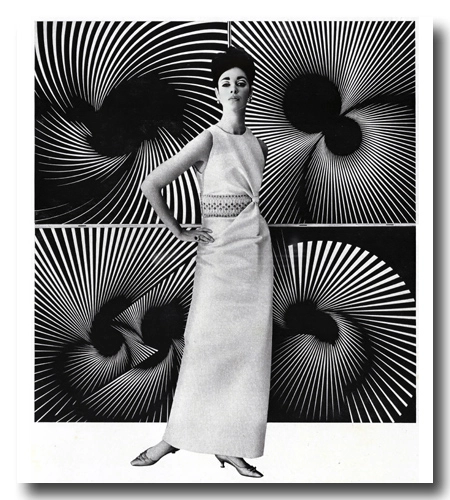

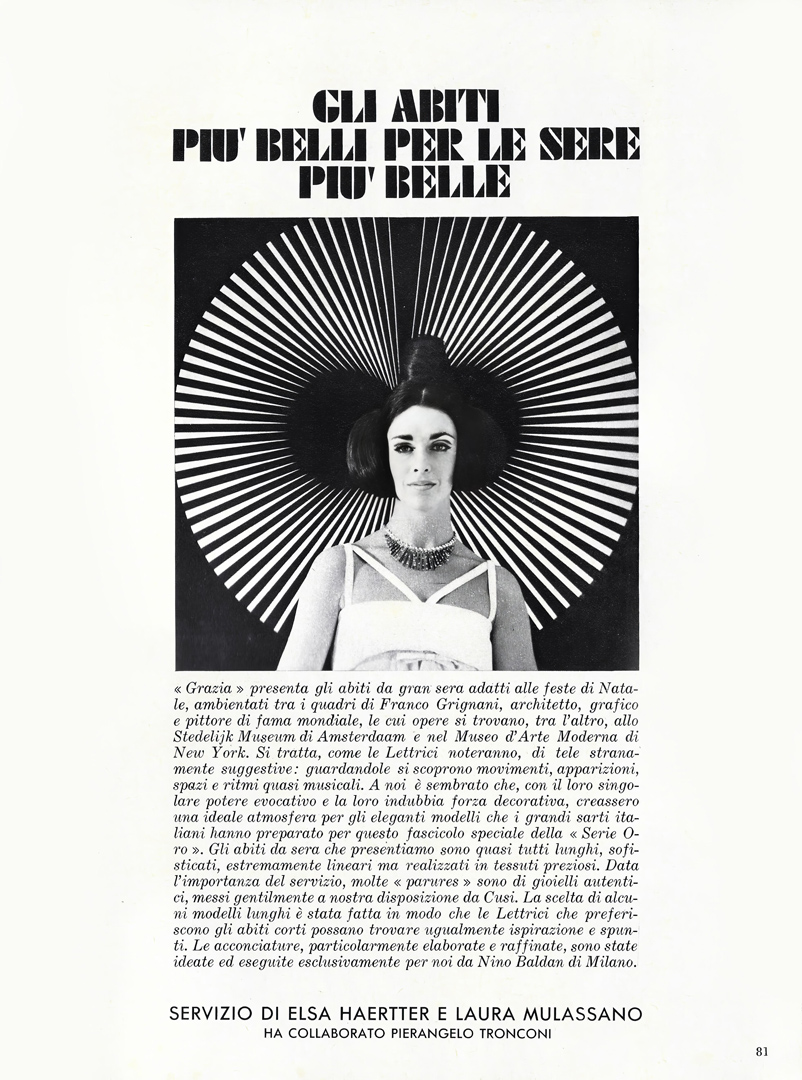

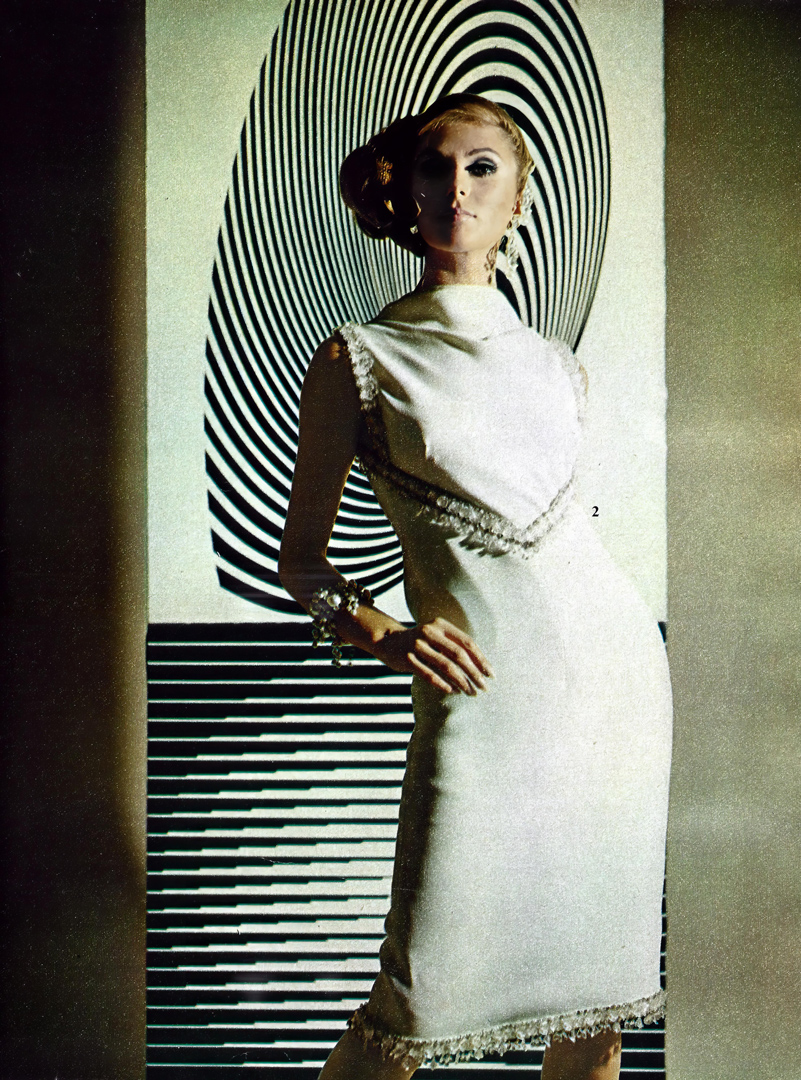

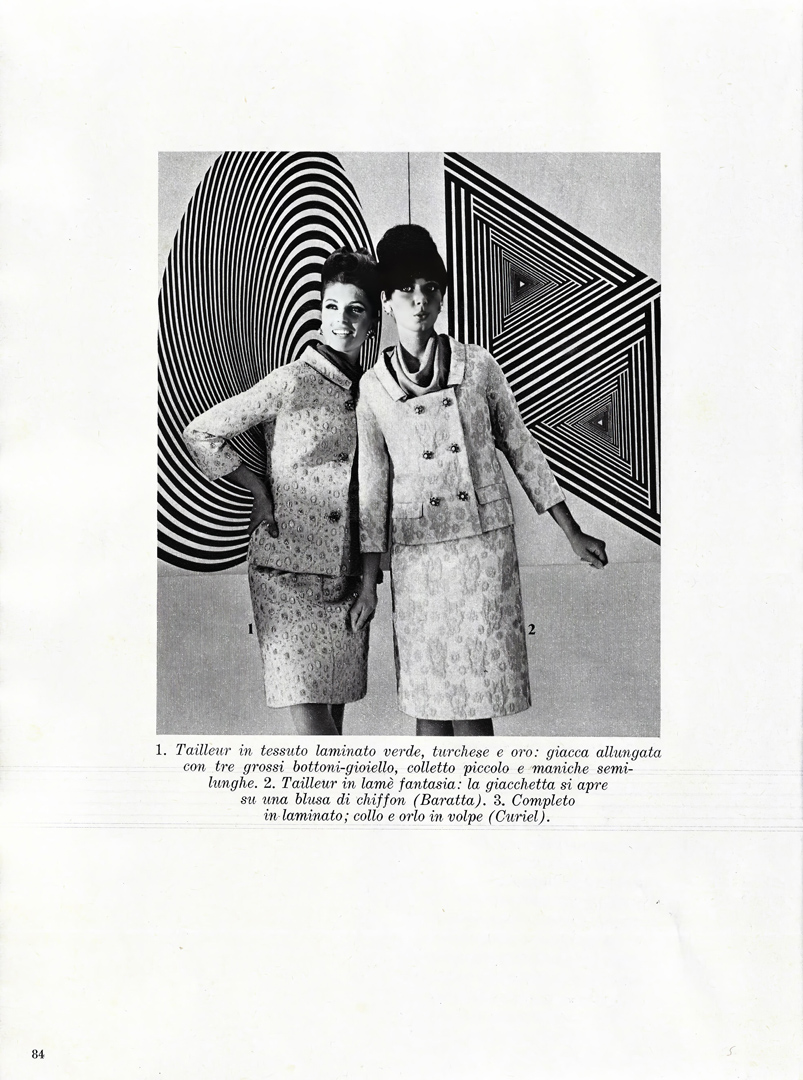

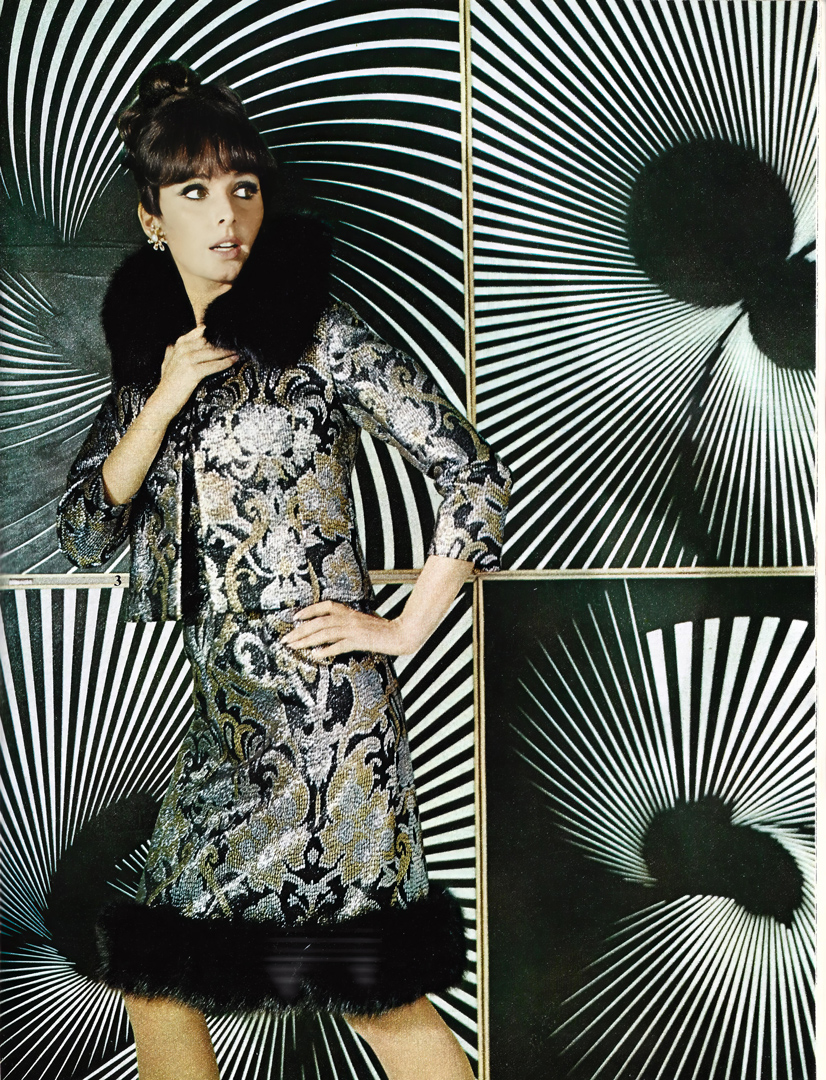

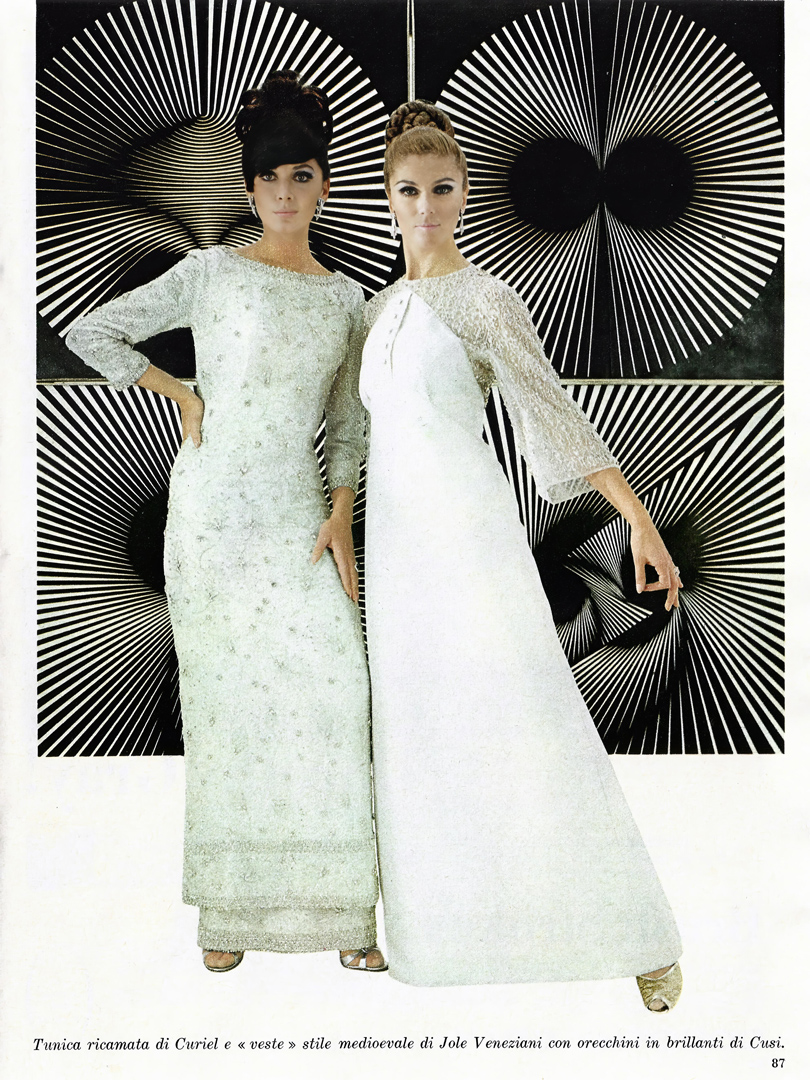

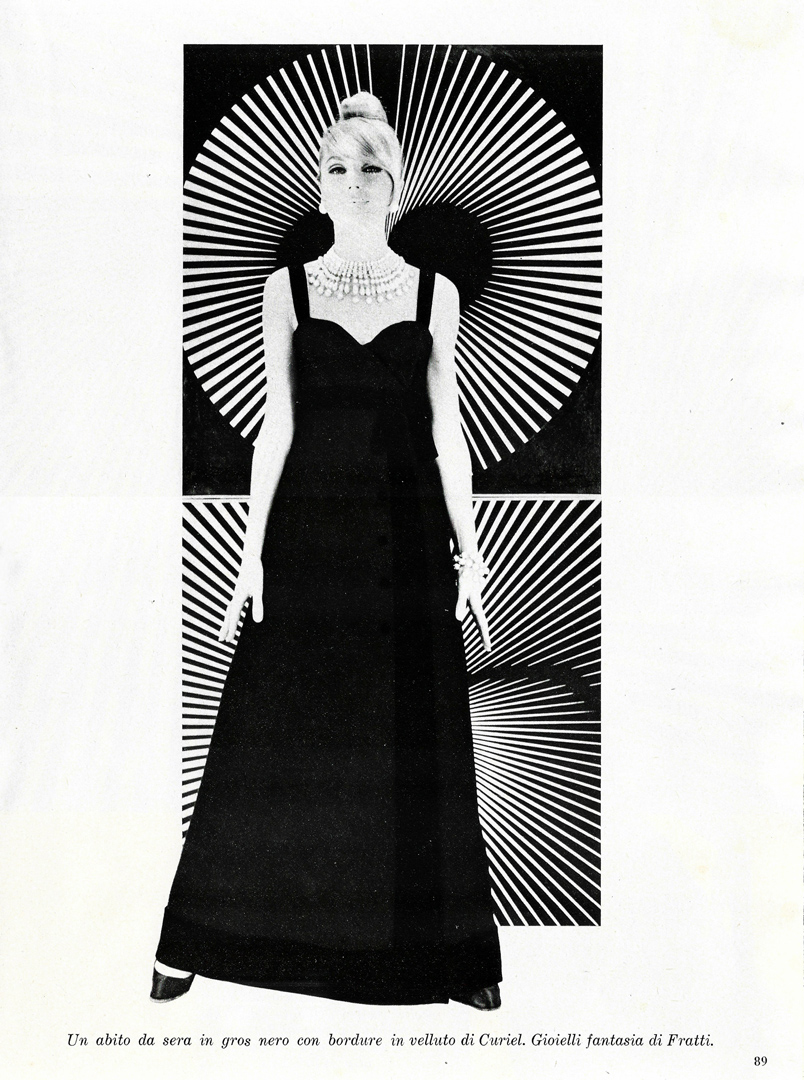

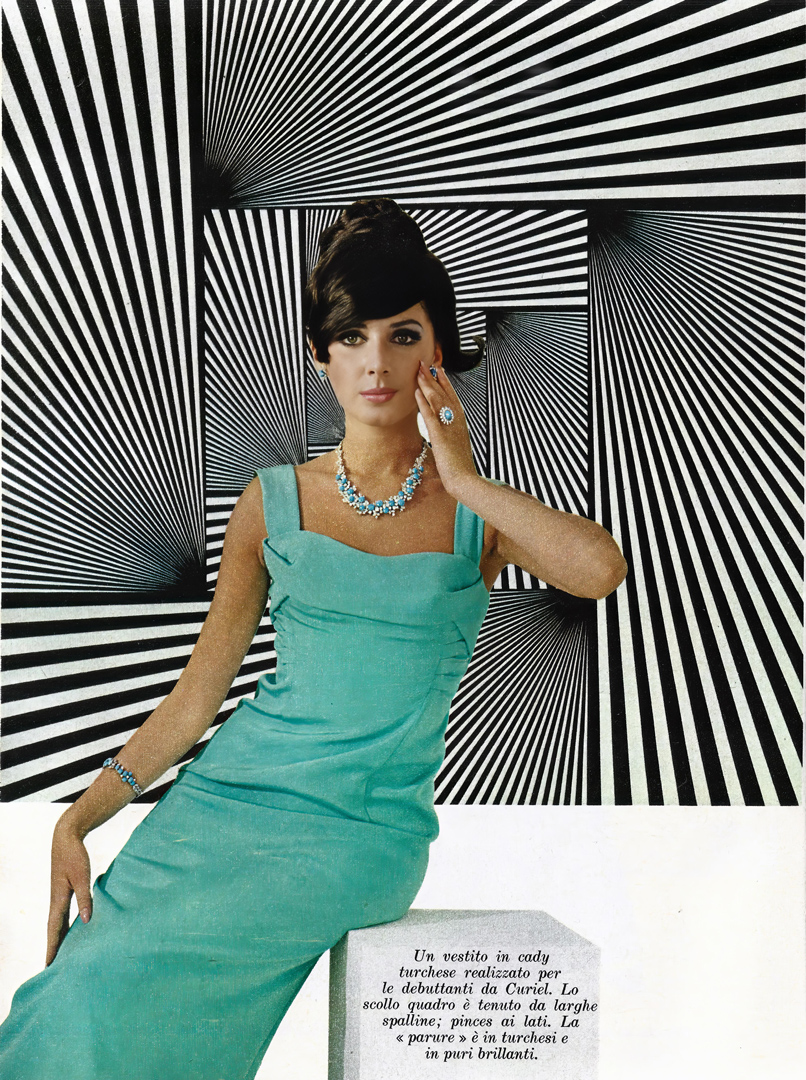

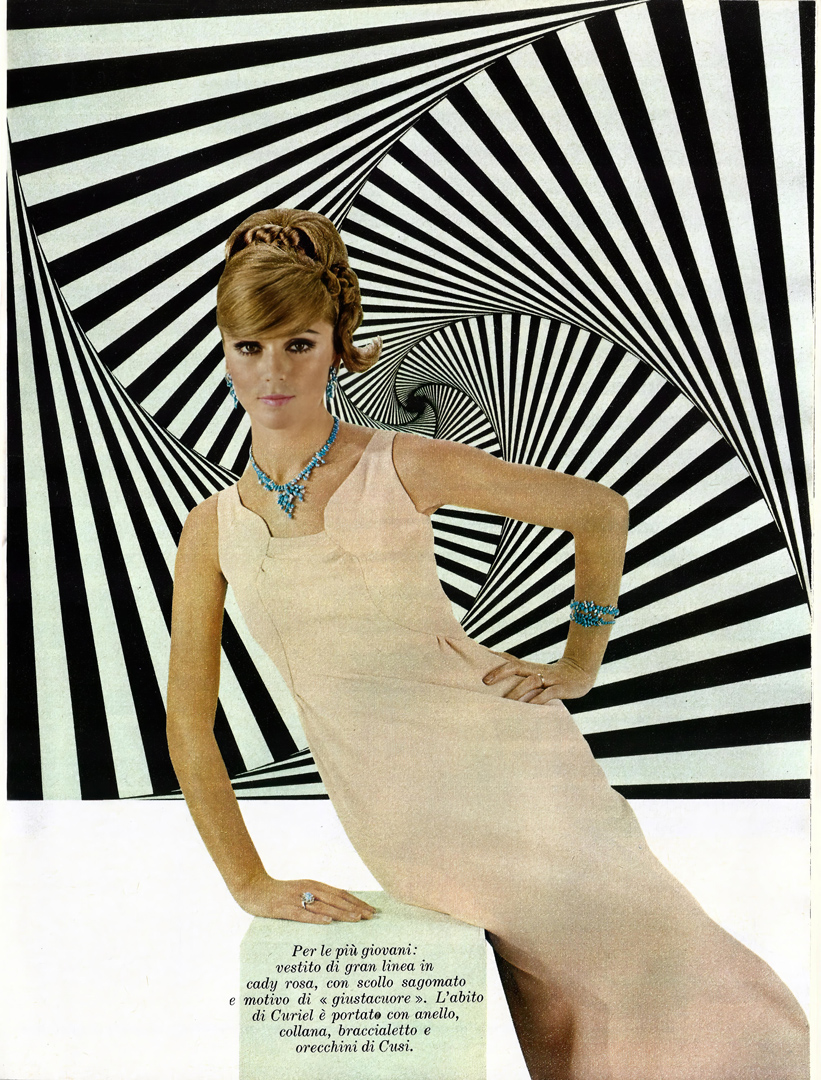

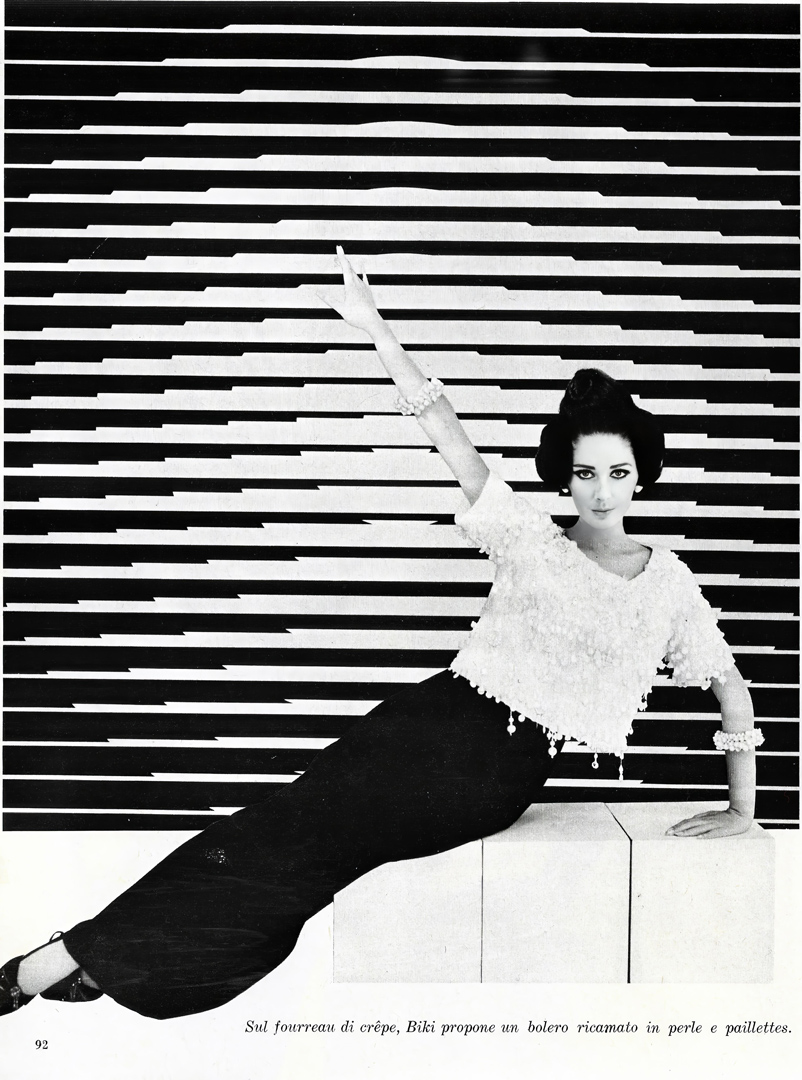

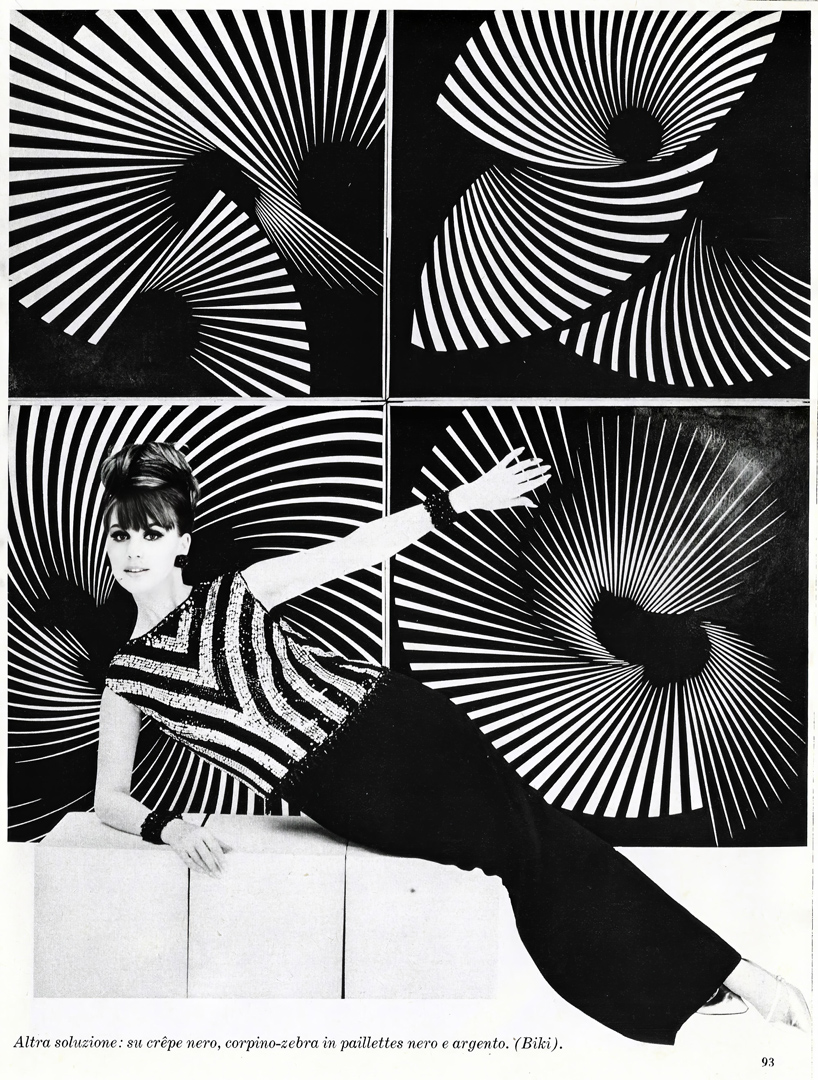

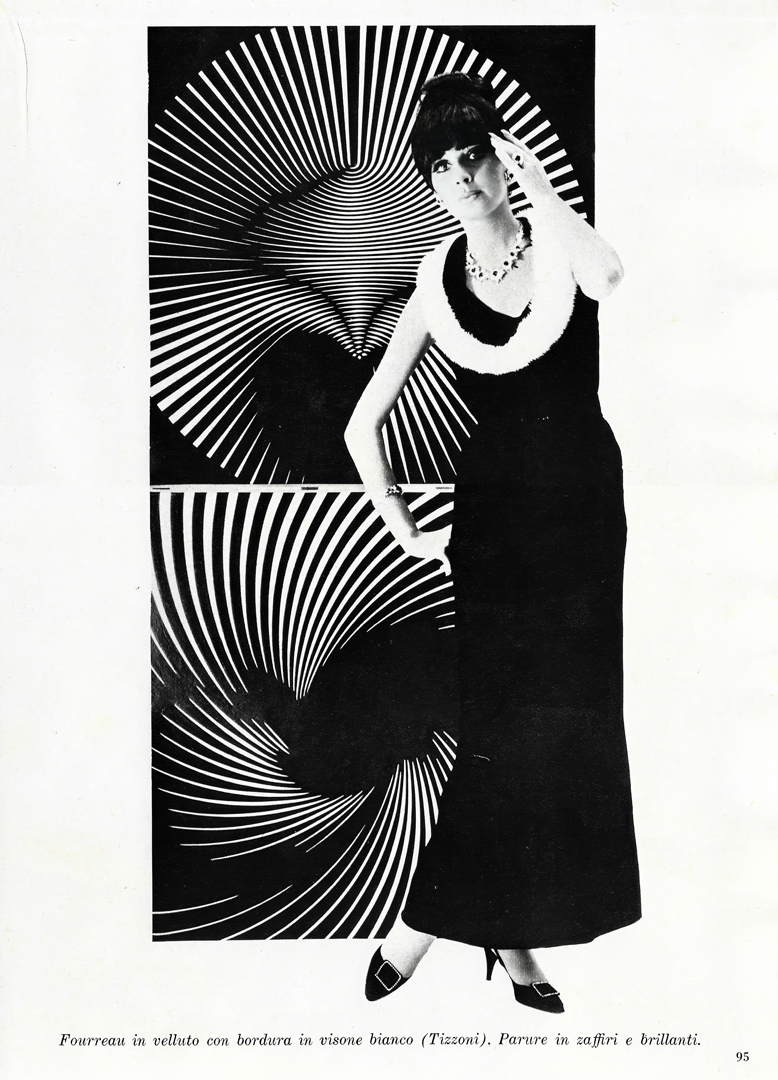

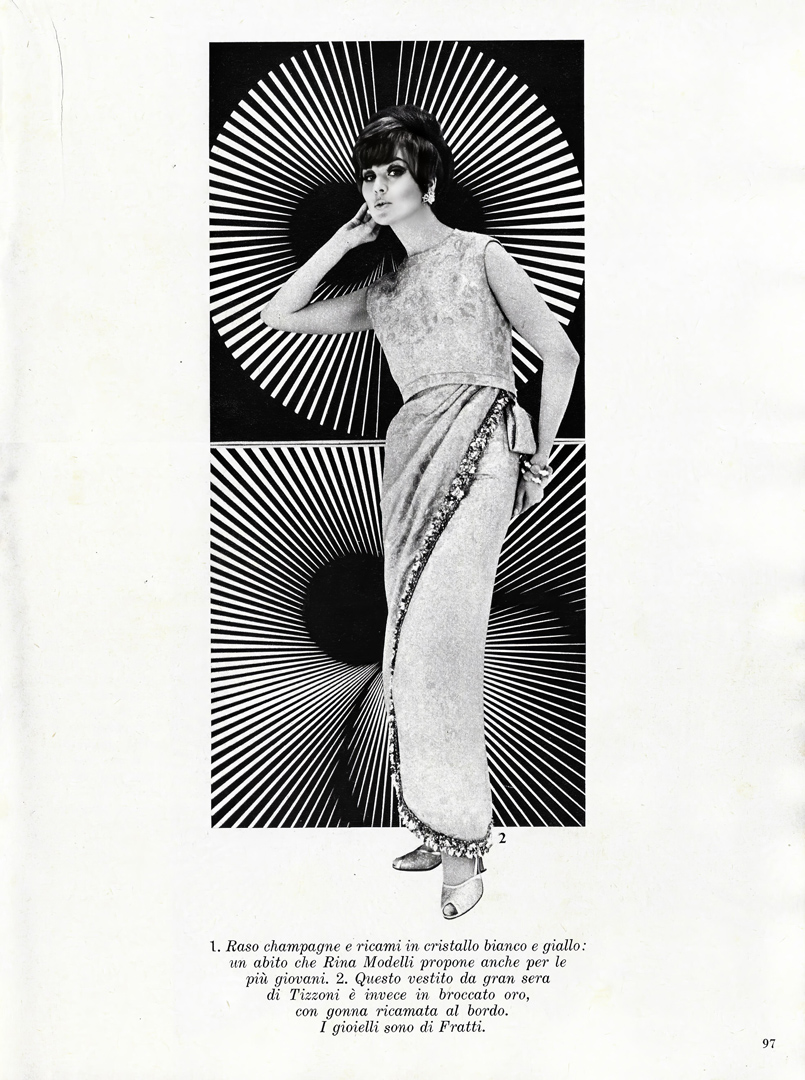

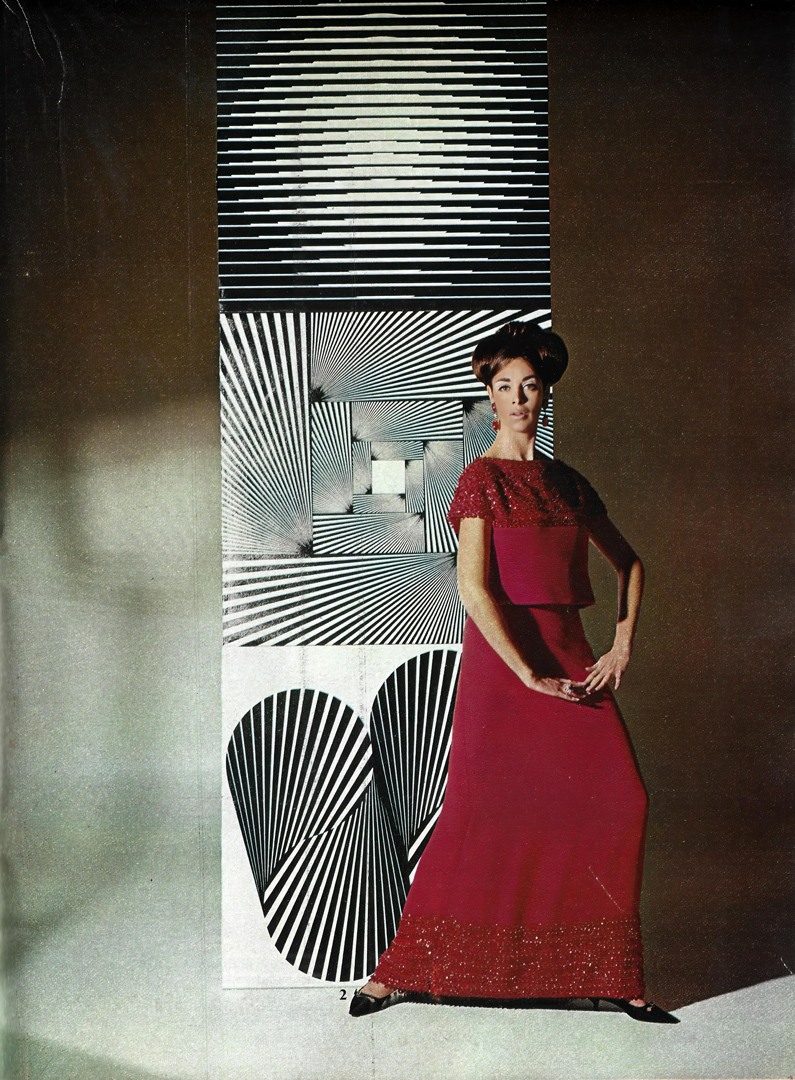

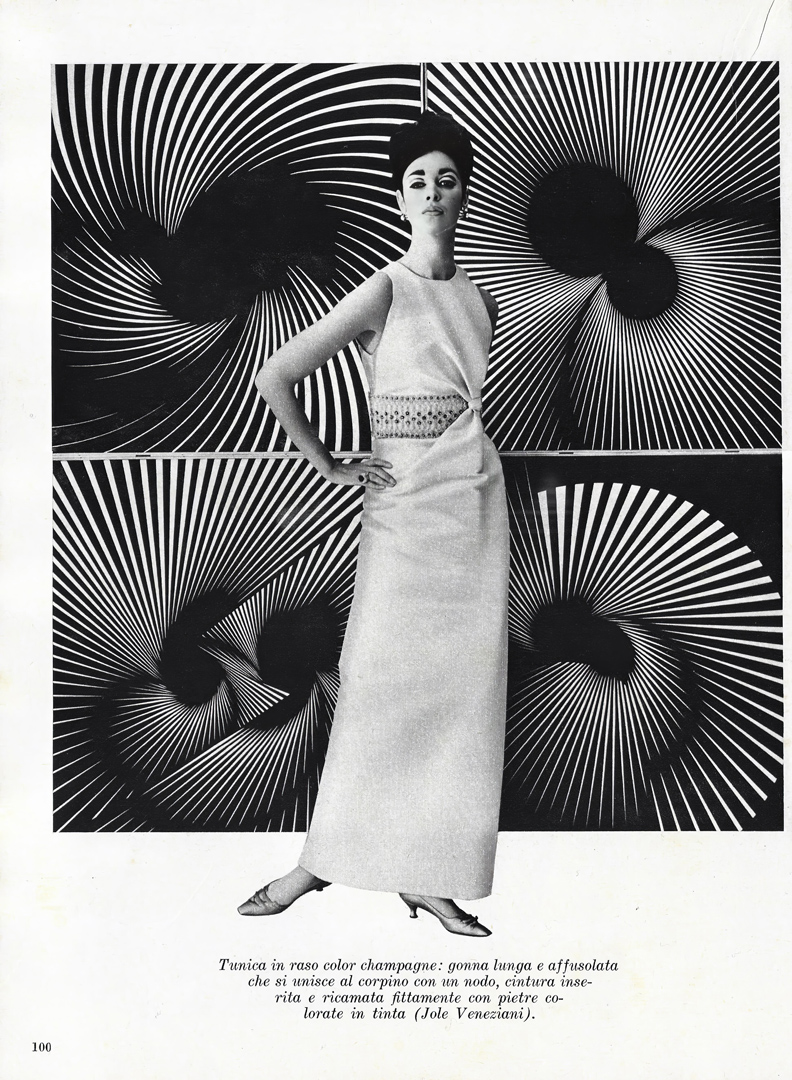

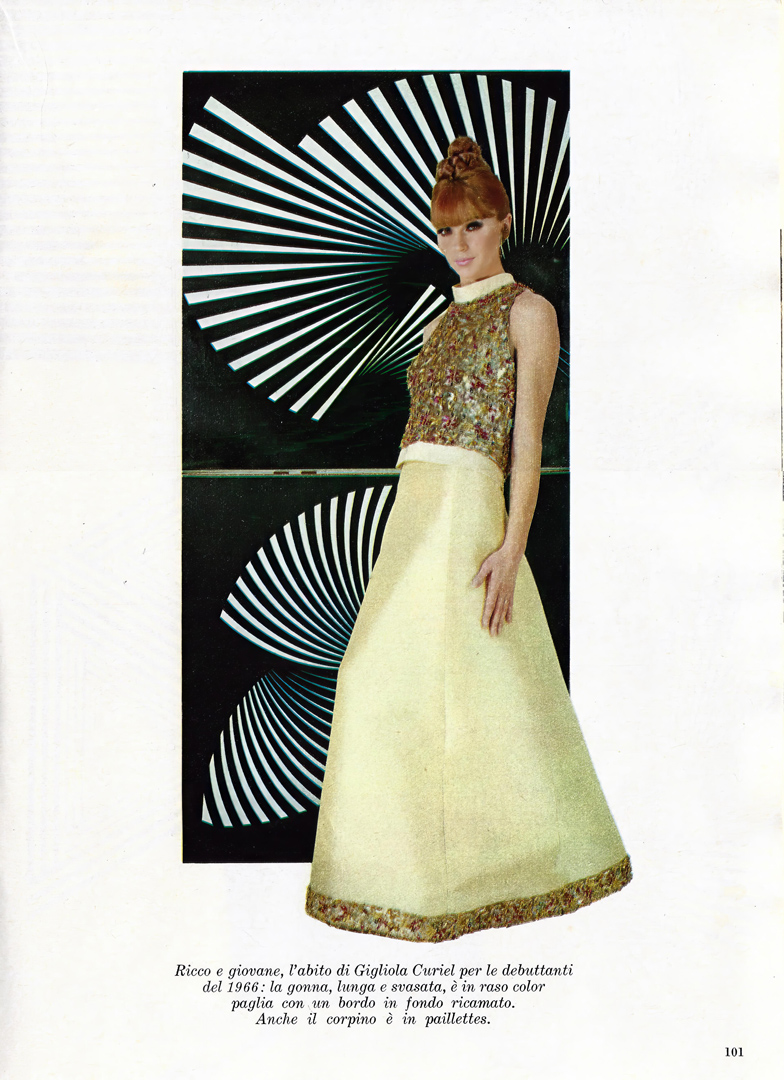

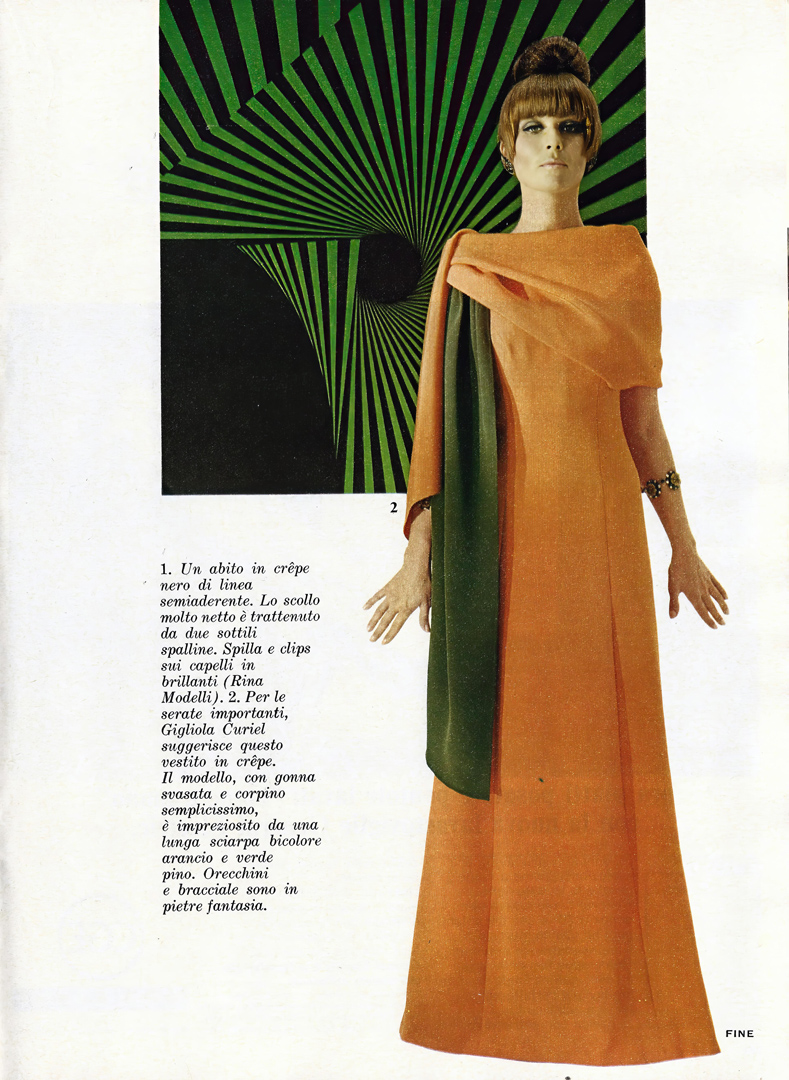

This 21-page article by Grazia magazine from 1965 highlights the intriguing dialogue between Franco Grignani’s artwork and fashion. His paintings were used as backdrops to showcase elegant evening gowns, blending art and fashion in a modern and evocative way. While the dresses were not optical in style, Grignani’s innovative aesthetics enhanced their presentation, creating a contemporary and immersive atmosphere.

THE MOST BEAUTIFUL DRESSES FOR THE MOST BEAUTIFUL EVENINGS

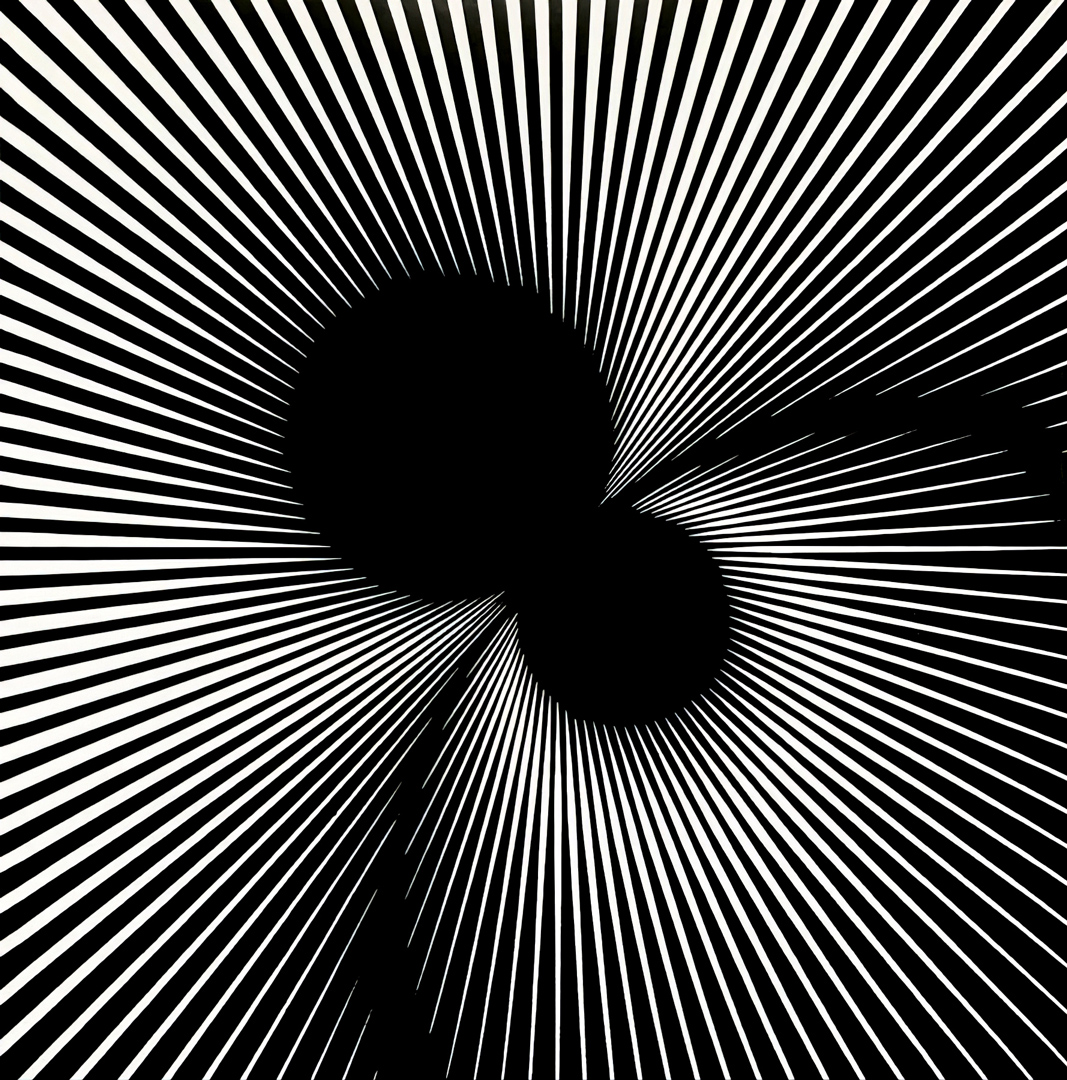

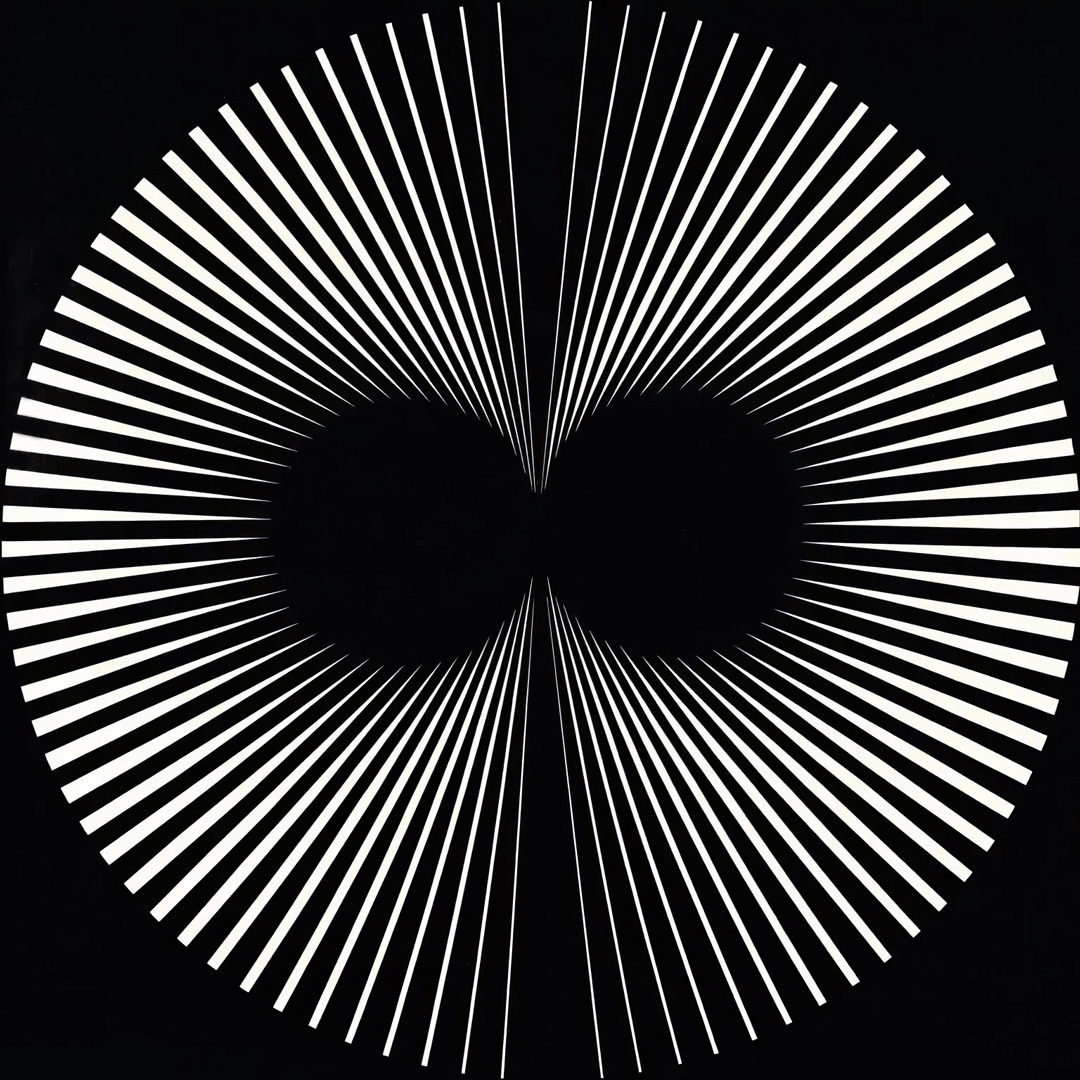

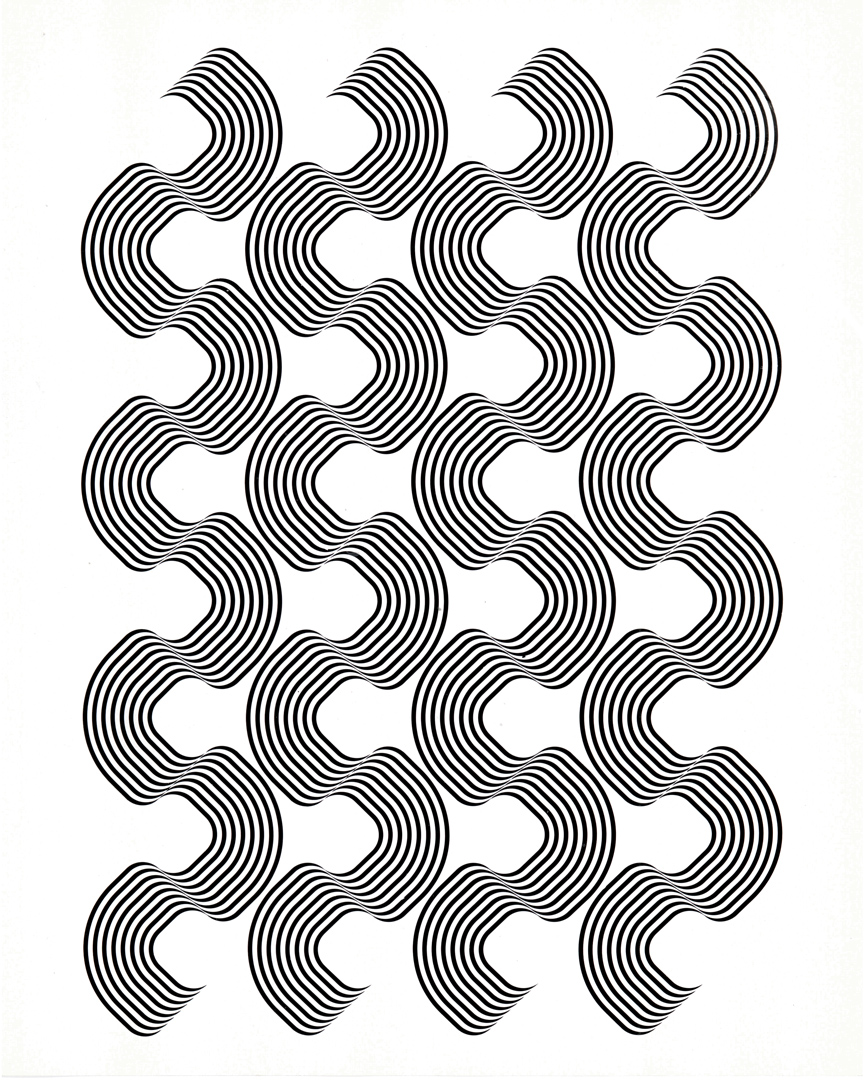

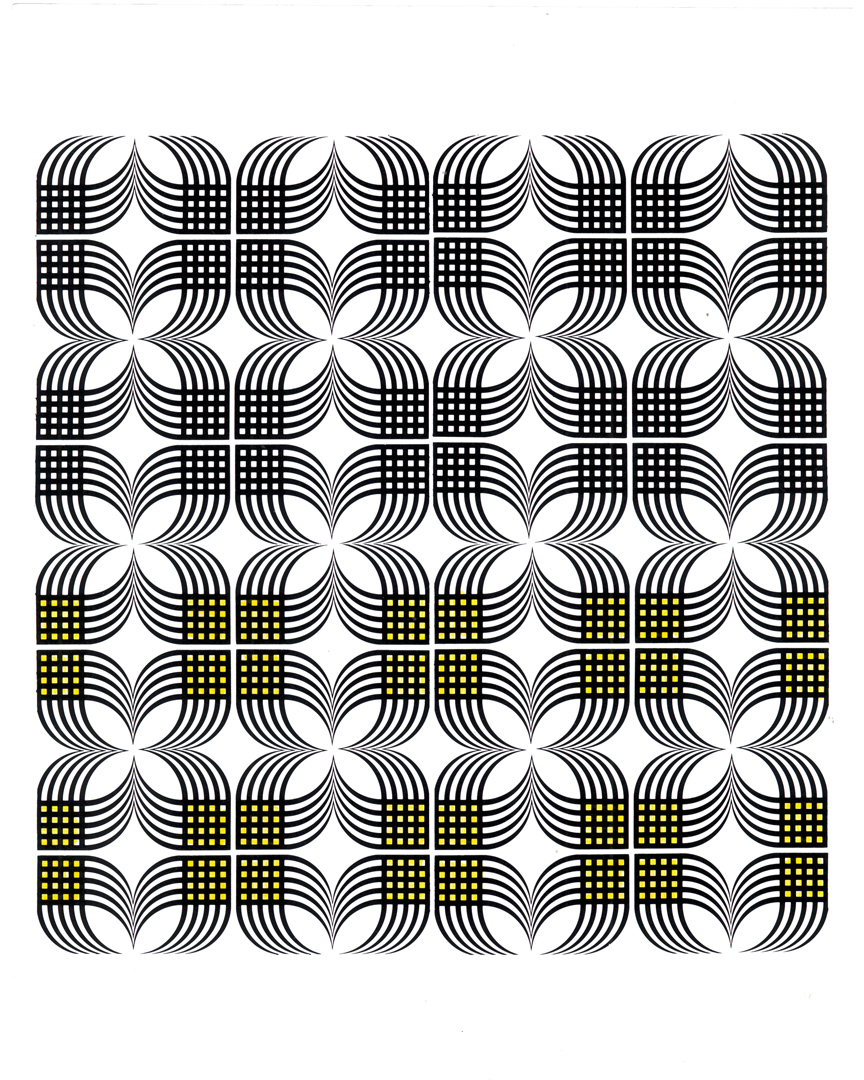

Grazia presents grand evening dresses perfect for Christmas festivities, set against the backdrop of paintings by Franco Grignani – architect, graphic designer, and painter of international renown – whose works are featured, among others, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. As readers will notice, these canvases are unusually evocative: upon observing them, one discovers movements, apparitions, spaces, and rhythms that are almost musical. To us, their unique evocative power and undeniable decorative strength seemed to create an ideal atmosphere for the elegant designs crafted by leading Italian couturiers for this special edition of the “Gold Series”.

The evening dresses we present are almost all long, sophisticated, and extremely streamlined, yet made from exquisite fabrics. Given the importance of this feature, many of the parures are authentic jewels kindly provided by Cusi. A selection of long dresses has been made so that readers who prefer shorter dresses can still find inspiration and ideas. The hairstyles, particularly elaborate and refined, were designed and created exclusively for us by Nino Baldan of Milan.

The article’s reference to “movements, apparitions, spaces, and rhythms almost musical” emphasizes the immersive quality of Grignani’s work, which amplified the elegance of the garments. His geometric patterns and optical illusions not only complemented the outfits but also added dynamism and modernity, reflecting the innovative spirit of the 1960s.

Grignani’s paintings were more than just decorative backgrounds; they became integral to the visual narrative, creating a harmonious composition where art and fashion interacted seamlessly. The models, set against his striking works, became part of a unified aesthetic that celebrated the fusion of clothing and art.

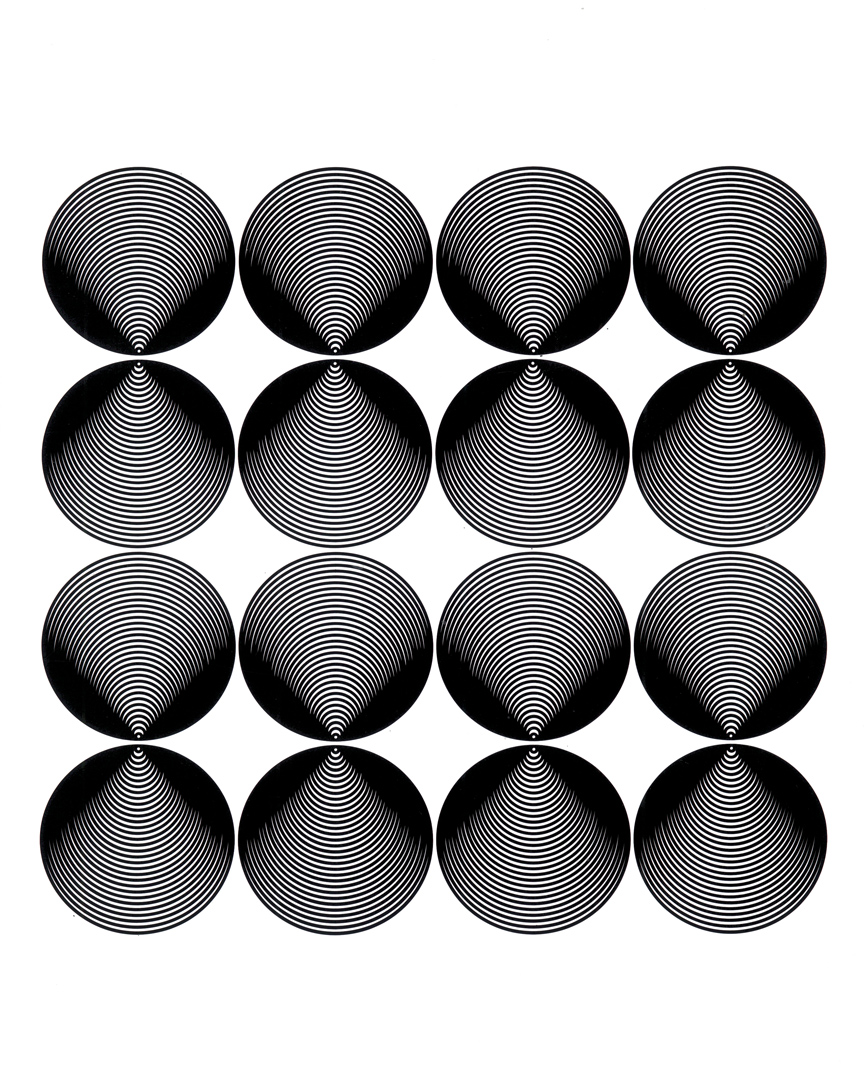

A selection of the paintings shown above:

Even today, the optical patterns and geometries of Grignani’s 1965 paintings continue to be a source of admiration, as evidenced by a record-breaking auction sale a few years ago, not to mention the timeless success of the Woolmark logo from 1963 (ultimately linked to the fashion industry, symbolizing quality and innovation in textiles).

Franco Grignani directly impacted fashion by creating fabrics adorned with his geometric motifs. The use of such patterns in textiles was revolutionary for its time, as it allowed fashion designers to incorporate avant-garde elements directly into clothing. Dubbed “wearable art”, these fabrics were not merely decorative but conveyed a sense of dynamism, innovation, and modernity, reflecting the experimental spirit of the 1960s:

Grignani’s ability to merge art and textile production showcased his versatility and extended his influence into practical and commercial realms. He continued this work into the 1970s, creating blankets, curtains, pillows, kakemono, and carpets – both independently and in collaboration with the ED Group – for companies such as Tessuti Mompiano, MB, Montedison, and Driade.

However, not everyone shared this perspective. For instance, Bridget Riley held starkly opposing views on commercializing her artworks. She expressed dismay at seeing her work (‘Hesitate‘, a painting featured in The Responsive Eye exhibition) adapted for prêt-à-porter fashion without permission, insisting her creations were better suited “to hang on a wall, and not a girl” [from ‘Fashion Op from Toe to Top: The Newest Style in Clothes Takes After the Newest Style in Art’, Life, April 16, 1965].

[6] GARADINERVI, courtesy of Robert Rebotti

[7] AIAP / CDPG Centro di Documentazione sul Progetto Grafico, courtesy of Lorenzo Grazzani

[37] Dorotheum

[all the other pics: courtesy of Daniela Grignani]

[I] ITA original text from the Italian-French magazine ‘arte e società’, 6/7, 1973: “A Tokio quest’anno, nell’invito ad una sfilata di alta moda, è stato usato un particolare tolto da una mia copertina per Graphis 1963.”

Last Updated on 01/02/2025 by Emiliano