During the latter half of the 1960s, Italy witnessed a period of redefining the roles of graphic and industrial design in society.

Facing the advance of the American-style ‘full service’ advertising agencies (as Simona de Iulio and Carlo Vinti recently underlined), in the debates promoted on the pages of Linea Grafica, Franco Grignani recognized industrial design as a new frontier for experimentation and research: “[…] advertising, as it has arrived today, marginalizes graphics. It has become a description, that is, it operates a descriptive act to provoke certain stimuli. Where graphics still intervenes, it is only to arouse areas of particular visual interest, but it is no longer so significant, so crucial in the advertising composition, where, instead, the image, especially the photographic one, has become prominent. Graphics today is more useful elsewhere. […] great graphics today walks hand in hand with design.” (Grignani, Struttura e decorazione: una scelta della grafica, Linea Grafica, 1, 1973 – [I])

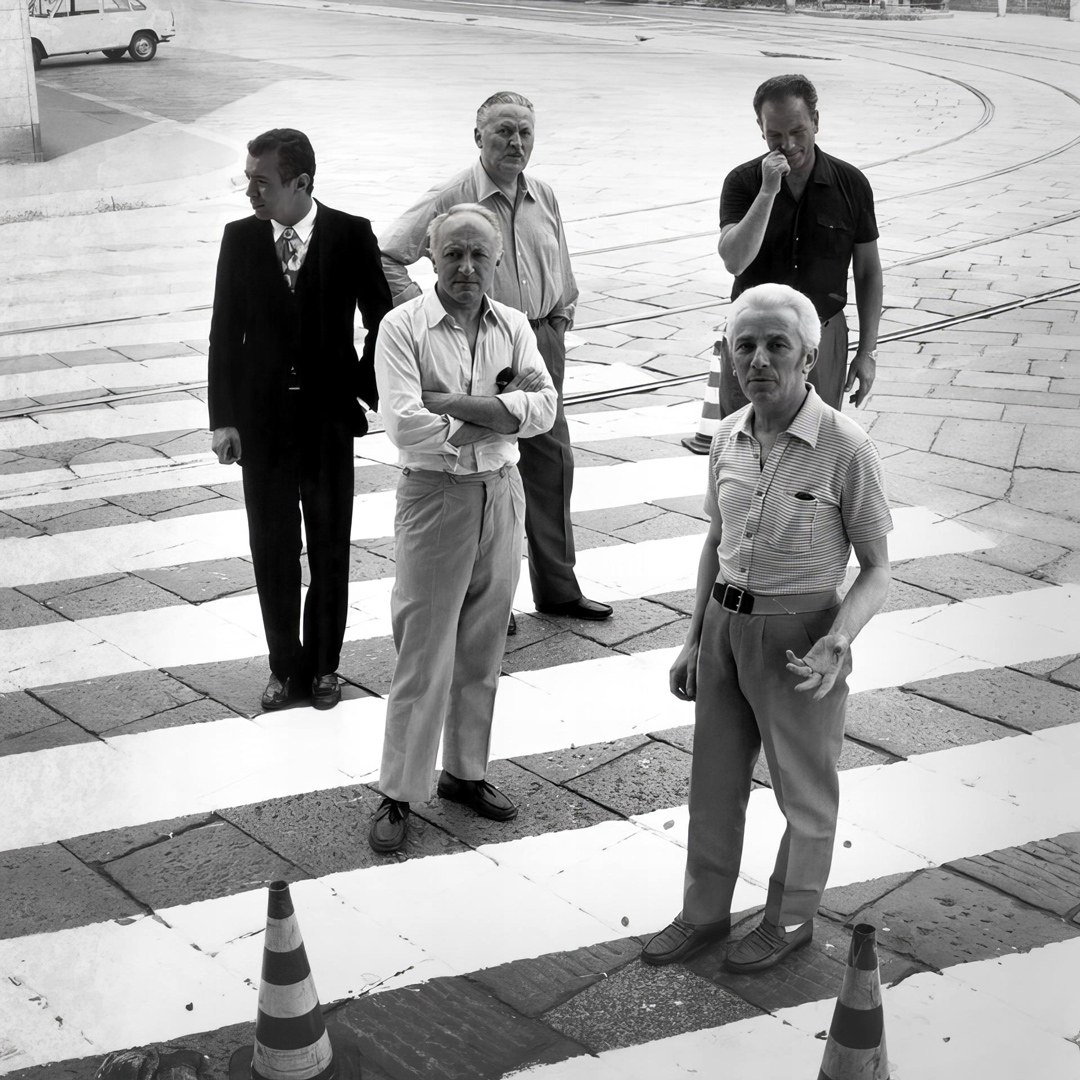

The Exhibition Design group (ED) emerged in Milan during these transformative years. This research, design, and dissemination group was established in 1968 and led by Silvio Coppola. It brought together prominent graphic designers of that era, including Giulio Confalonieri, Franco Grignani, Bruno Munari, Pino Tovaglia, and, by 1970, Mario Bellini. The group’s primary objective was to explore the convergence between the methodologies of graphic design and those of industrial design. Specifically, they focused on the concept of the so-called ‘pre-design’, that is, “the activity that precedes the actual project and has as its object the collection of material and technological data” [from ‘Graphis’, n° 145, 1970].

While these designers operated independently, they frequently signed their projects collectively, deliberately demonstrating their collaborative approach and methodology.

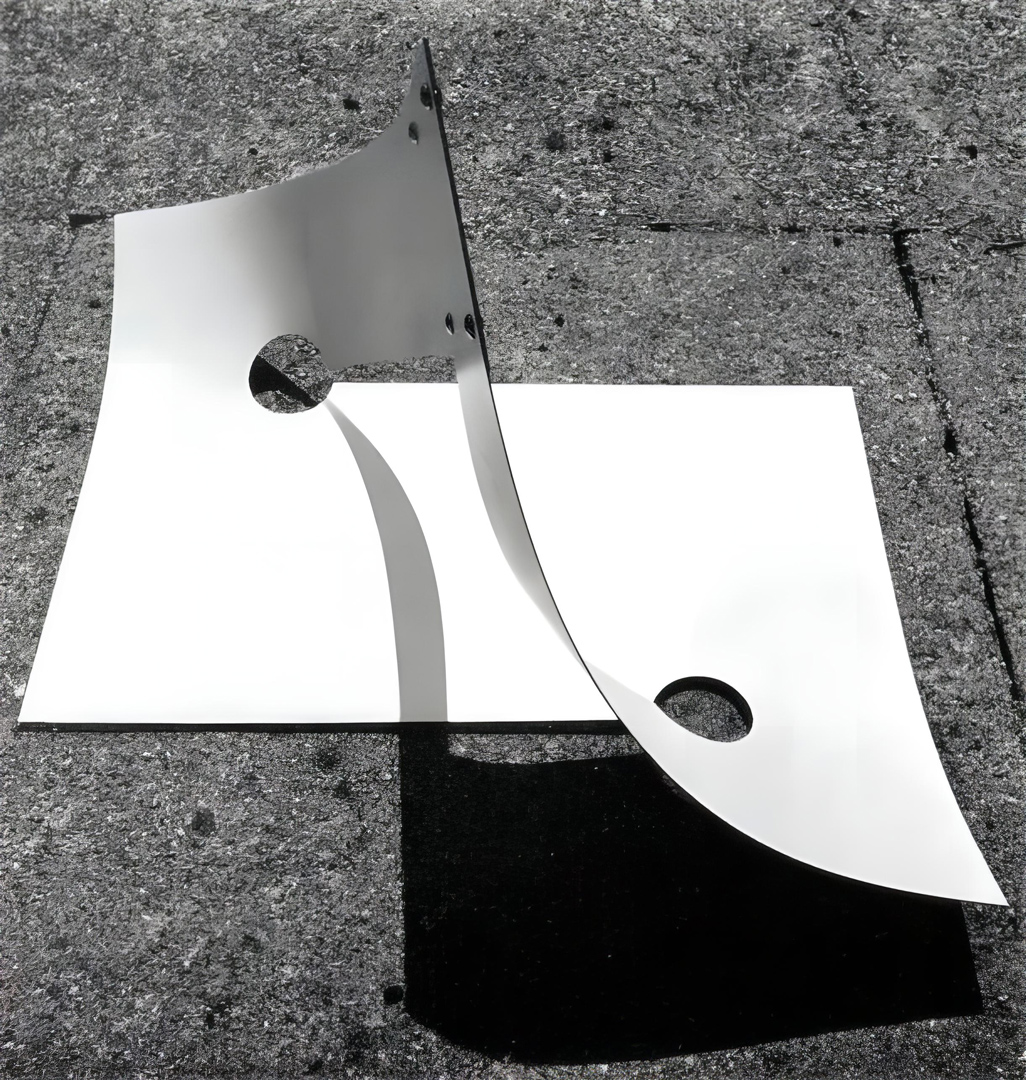

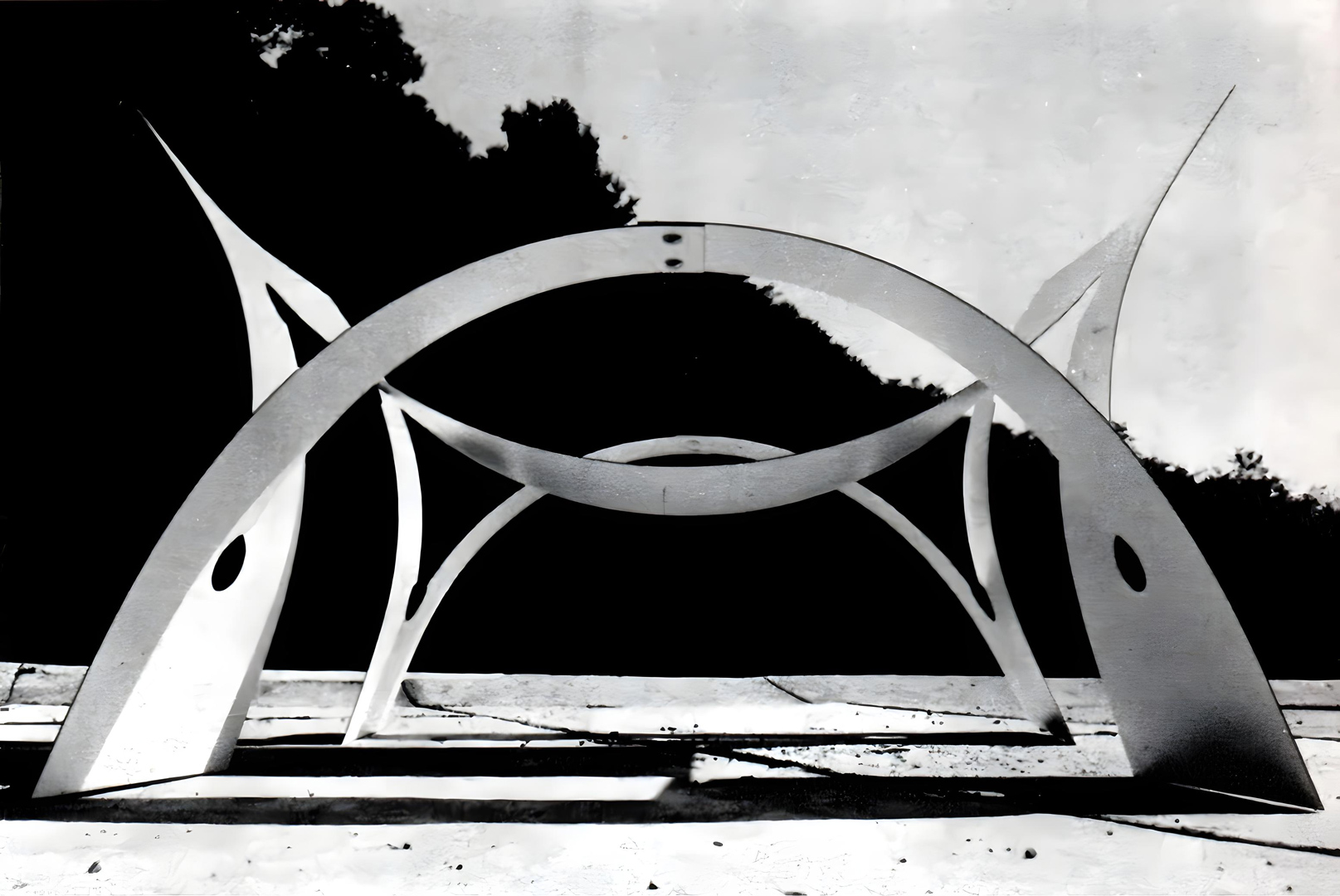

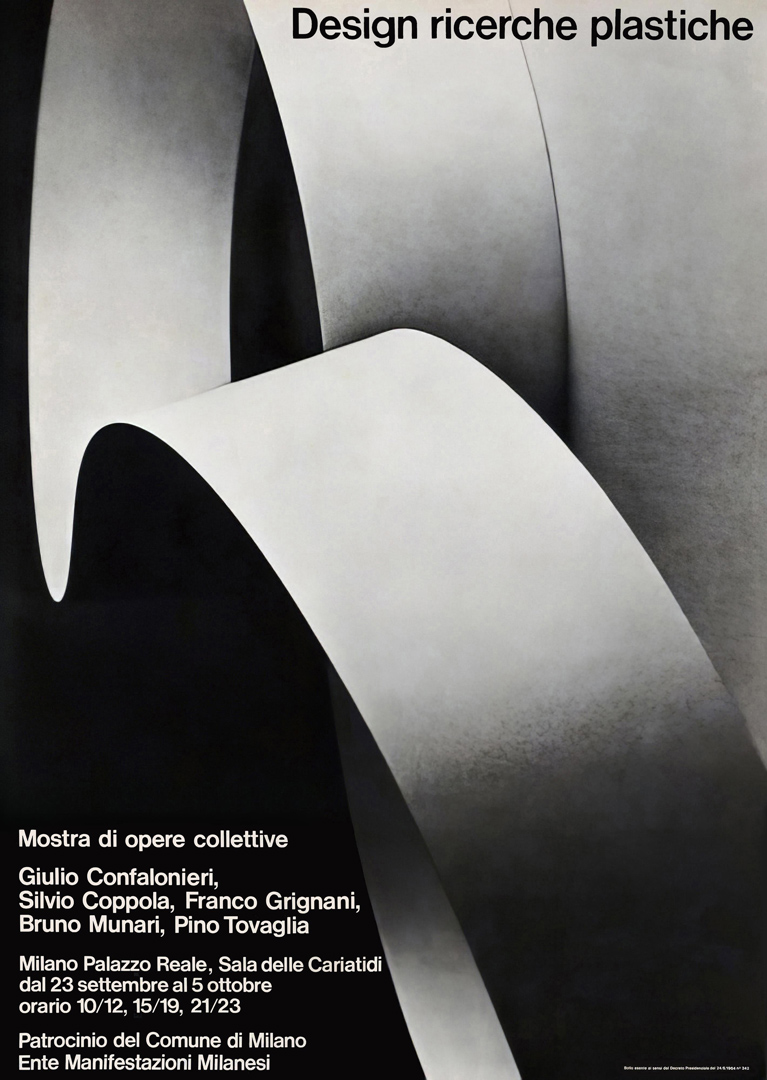

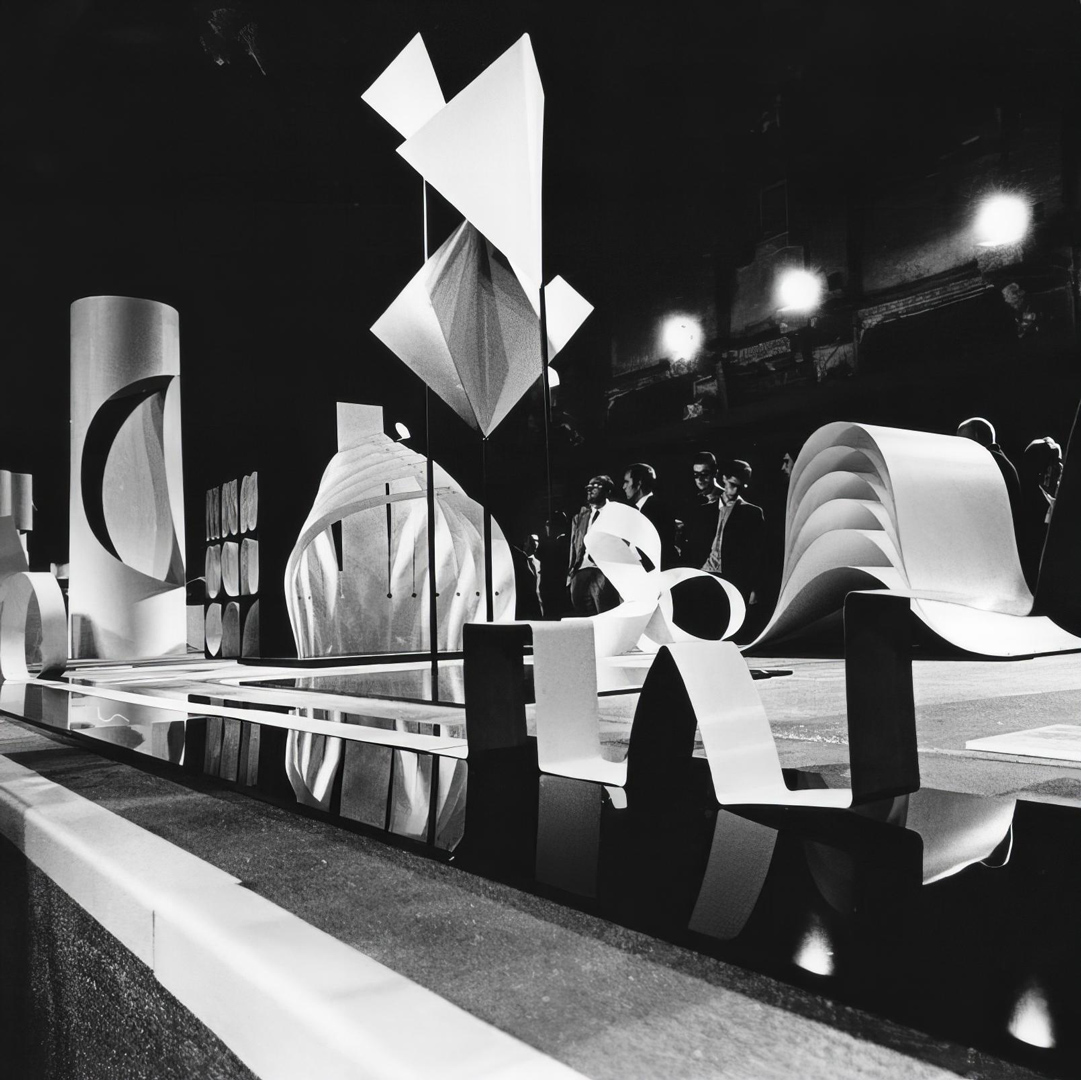

On September 22, 1969, the first exhibition of the Milanese group, Design ricerche plastiche (Design plastics research), was inaugurated at the Sala delle Cariatidi of Palazzo Reale in Milan. The exhibition showcased a series of 22 experiments – placed in the middle of a large curious audience remarkably photographed by Ugo Mulas & Luciano Ferri – conducted around the Formica® plastic laminate. These experiments were conducted in collaboration with two companies: Soc. Laminati Plastici (which supplied the material as the licensee for Formica Intl. Ltd. in Italy), and G.B. Bernini & Figli (which assisted in preparing the exhibition). “This last research was carried out by a group of designers who reciprocally exchanged the results of individual experiments, thus obtaining a set of models in which all had participated in the realization” [from Bruno Munari in ‘design’ magazine, n° 3, 1974]. “The group presented the resulting pieces of this research for new uses of the same material outside the use that is normally made of it in the field of furniture surface coatings” [from ‘Ottagono’, n° 22, 1971]. “The designers now plan to explore the problems of spatial design which are rapidly gaining in significance in our own age” [from ‘Graphis’, n° 145, 1970].

As recently pointed out by Michele Galluzzo, the collective group saw this exhibition as an opportunity to gauge public opinion and share the results of their surveys and working methods.

“The Designers: Giulio Confalonieri, Silvio Coppola, Franco Grignani, Bruno Munari, and Pino Tovaglia, have formed a Group for planning Special Exhibitions […] relating to the designer’s work. […] The Group will ask for the co-operation of those Experts required by the type of the research involved following the most objective method of design.”

[from the exhibition catalogue]

Hence, the group aimed to showcase not just the finished product and its aesthetic aspect, but primarily the logical method they employed. In fact, in a small article that appeared in the magazine ‘Abitare’ (n ° 78, Sept. 1969) entitled “story of a strip” (with reference to “these characters who walk around the corridors and courtyards of a factory with a long strip of flexible material”), it is highlighted that “the resulting objects may have points of resemblance to what is now called sculpture or programmed research, but the authors who work or sign in the group have not worked with intentions of art but have been stimulated by the curiosity of free experimentation.”

The poster of the exhibit was also shown in Chicago, at the 500-D Gallery, in 1970, and in various international graphic magazines.

Among the various subsequent initiatives in the field of industrial design, the ED Group developed a series of ceramic tiles for the Milan-based company Cilsa, offering individual designers the opportunity to pursue their unique research using new media and novel contexts. This approach aligned with the principles highlighted in the exhibition “Italy: the new domestic landscape“, a showcase of Italian design held in 1972 at the MoMA in New York.

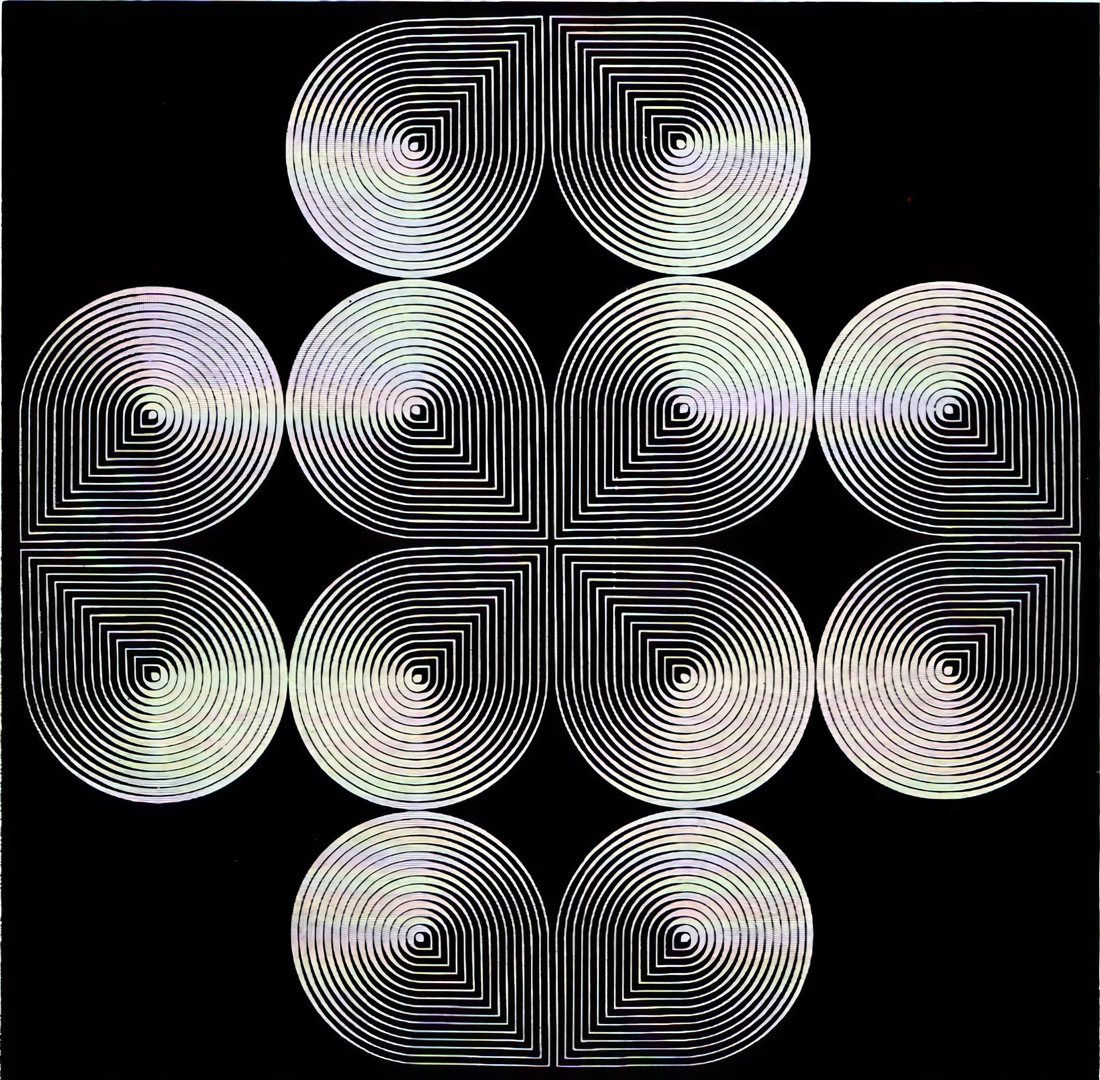

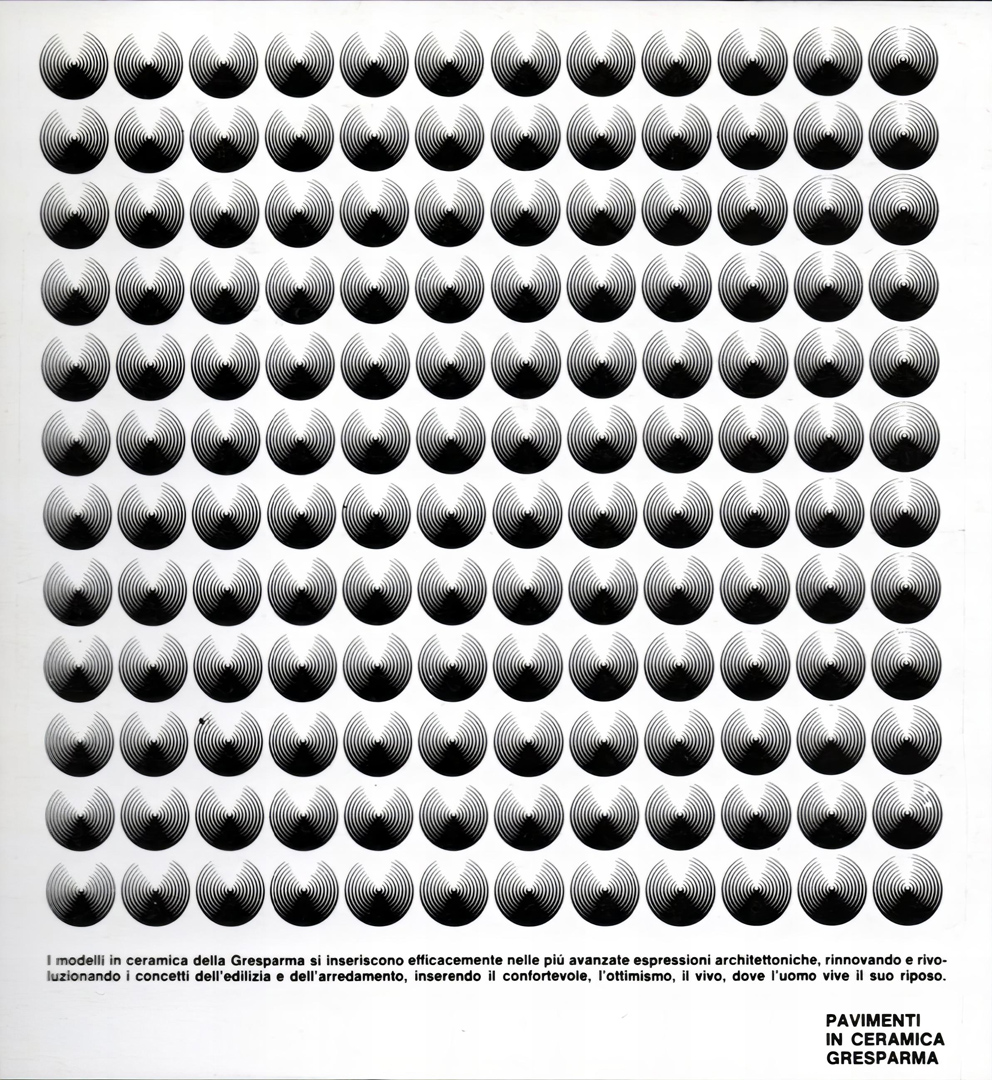

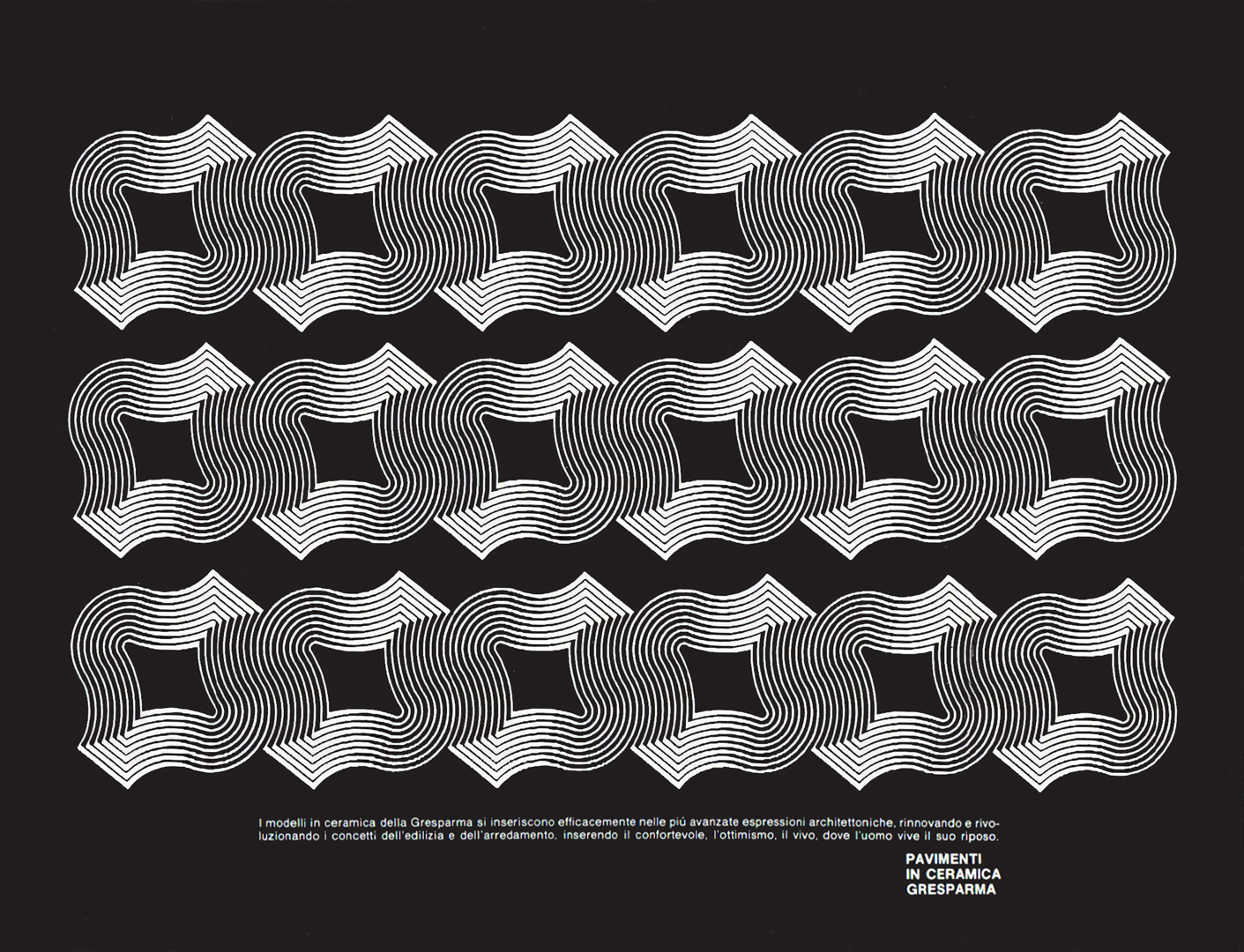

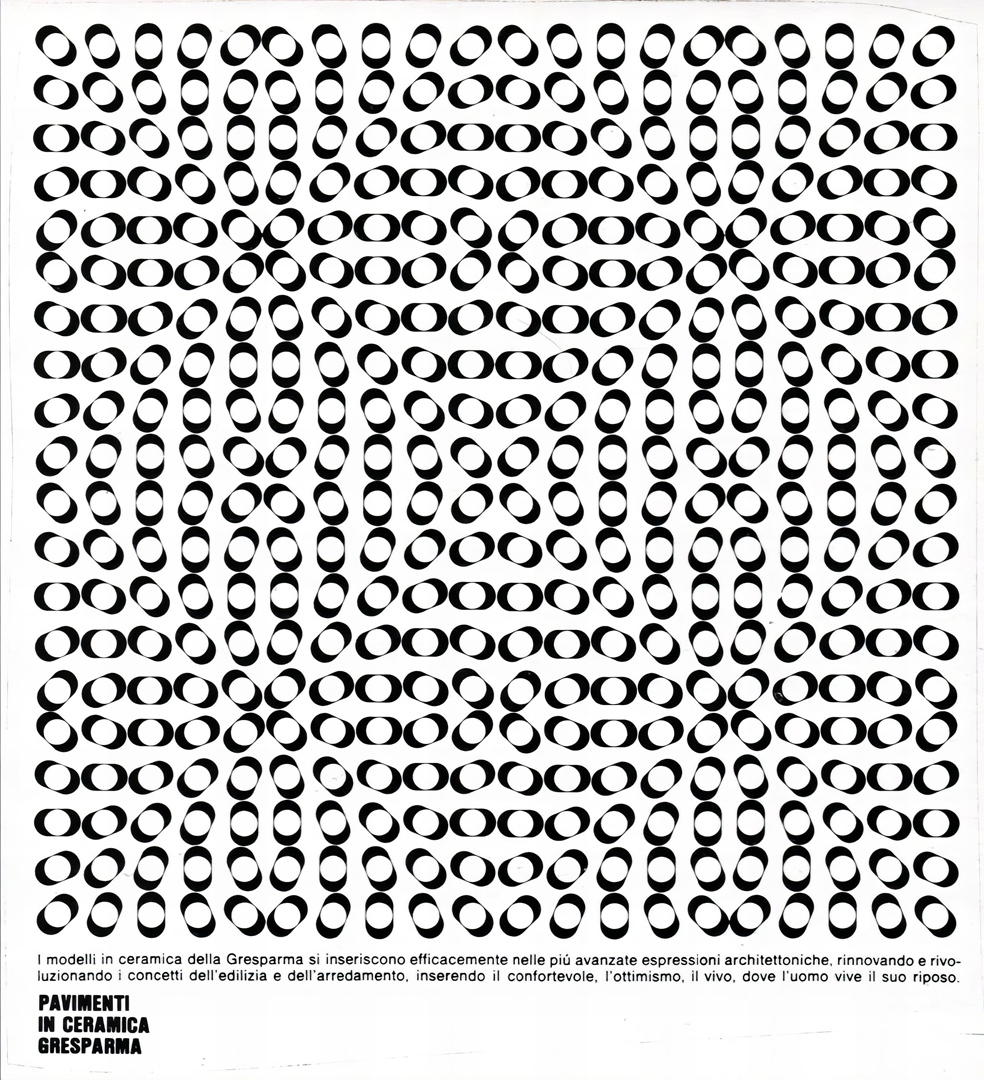

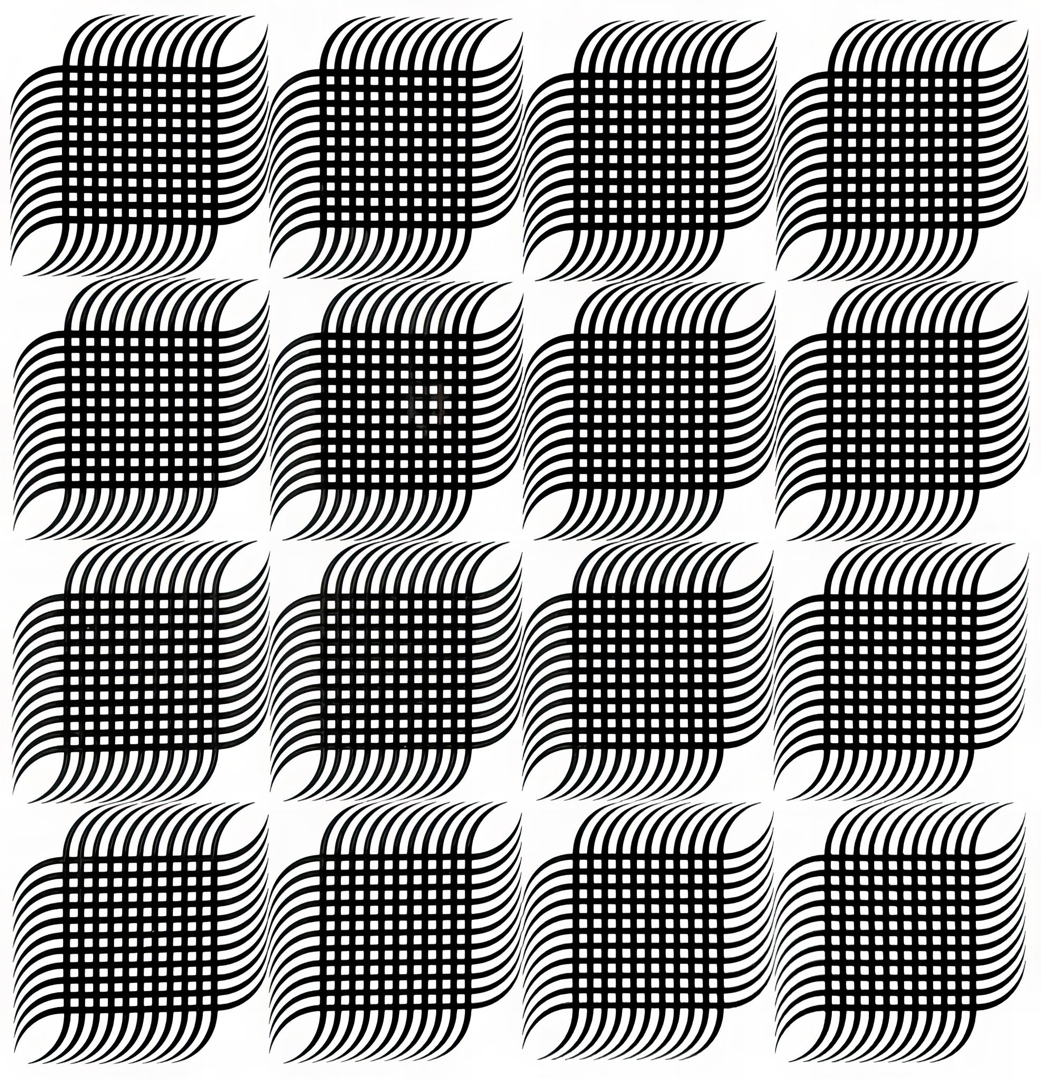

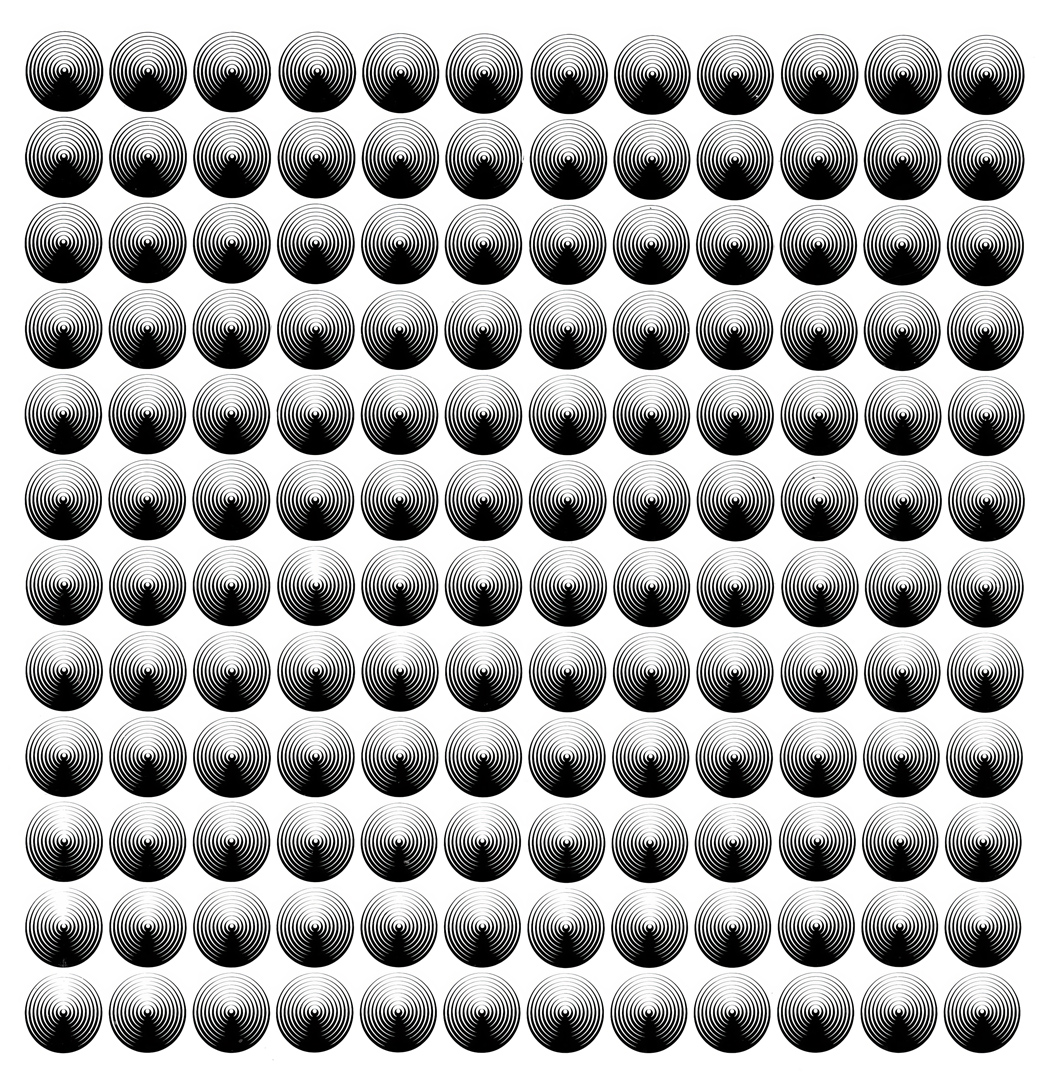

The research conducted by the ED Group was closely linked with the work of individual designers. This methodology is evident in Franco Grignani’s Matassa tile, which builds upon the theme of the Woolmark logo with a quadrilobed optical decoration. Similarly, in the case of Ceramica Gresparma, Grignani developed a modular tile: “this floor has a modular compositional structure of light and shadow and, using the perspective vision, proposes illusory plastic-dynamic effects” [II]. This modular design concept had its origins in earlier studies dating back to 1966:

Grignani pointed out: “The diffusion of the decoration acquires increasing resonance with the advent of the machine. The explanation is that, essentially, the machine favours the creation of repetitive patterns in a decorative sense. Let’s think of the textile sector, ceramic production, etc.” [III]. The use of screen printing on ceramics was also evidenced by the tile Spica, designed by Grignani in 1976 for Ceramica Faetano, a project in which Bruno Munari and Pino Tovaglia also participated. An exhibition entitled “Author’s Surfaces” was set up at the Domus Center in Milan in October 1976 to showcase these new tiles.

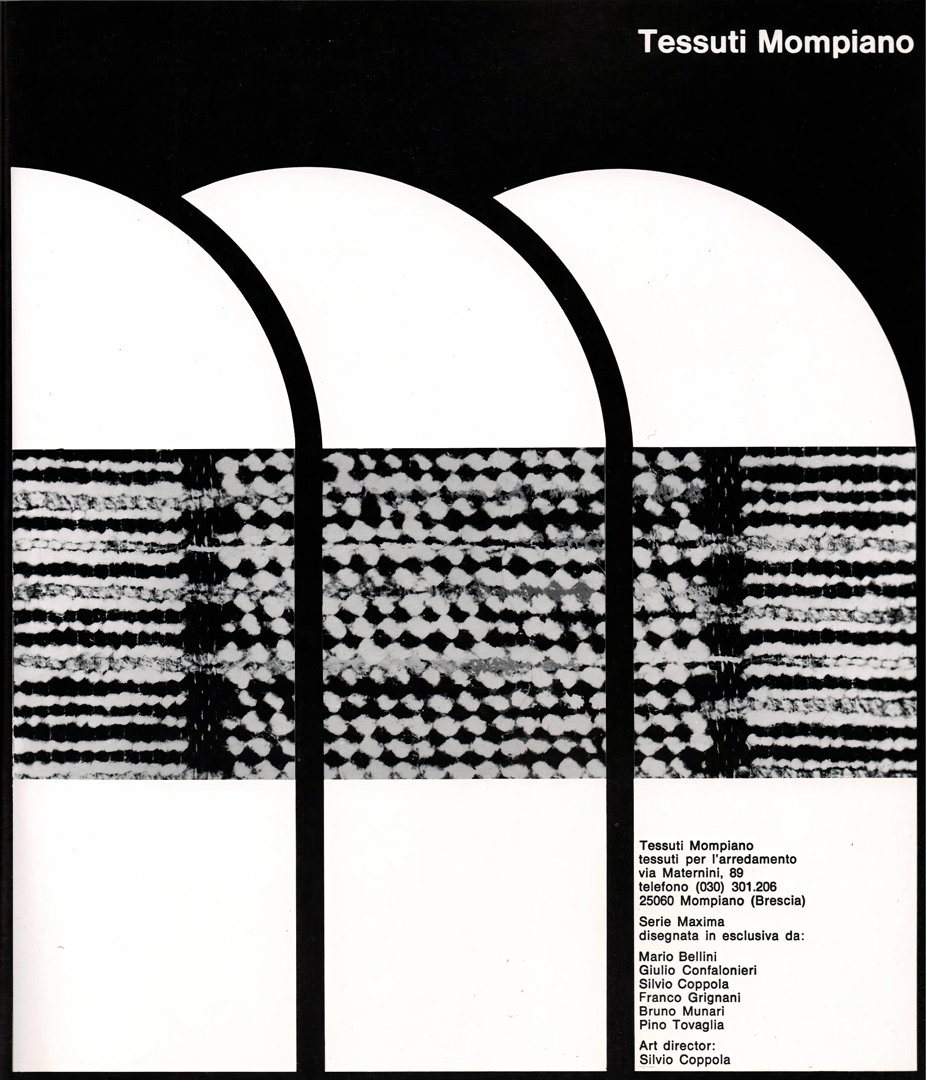

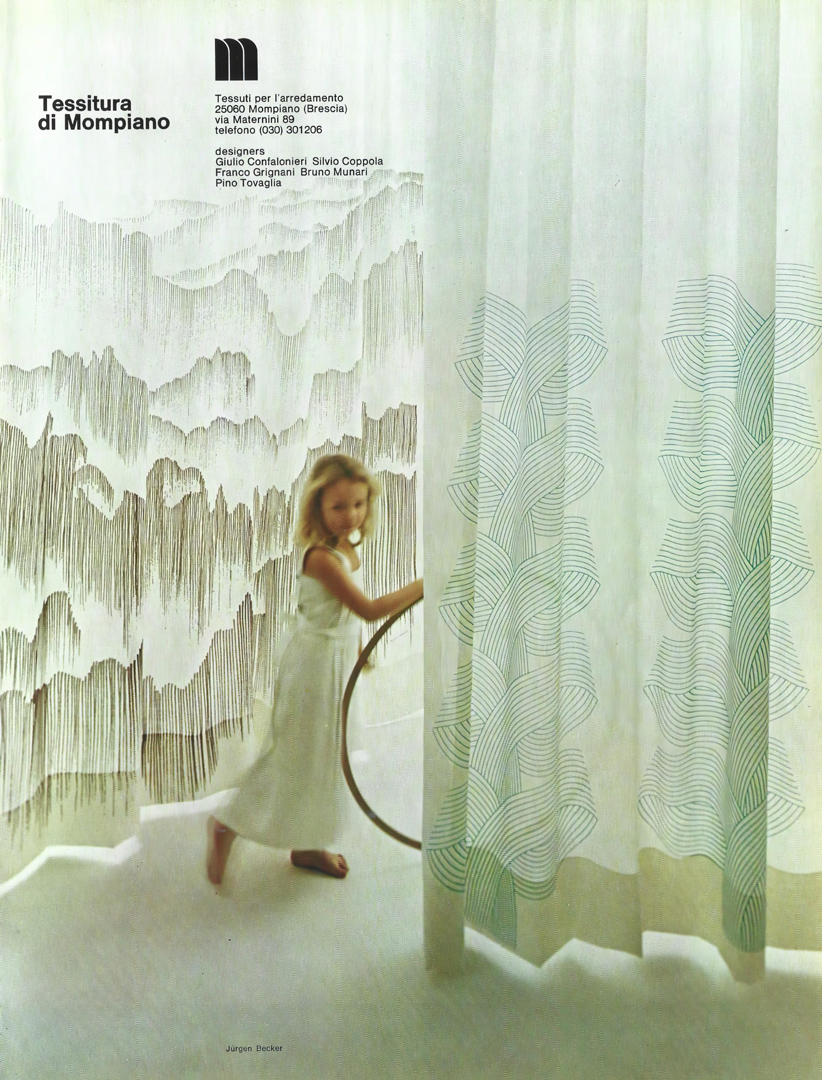

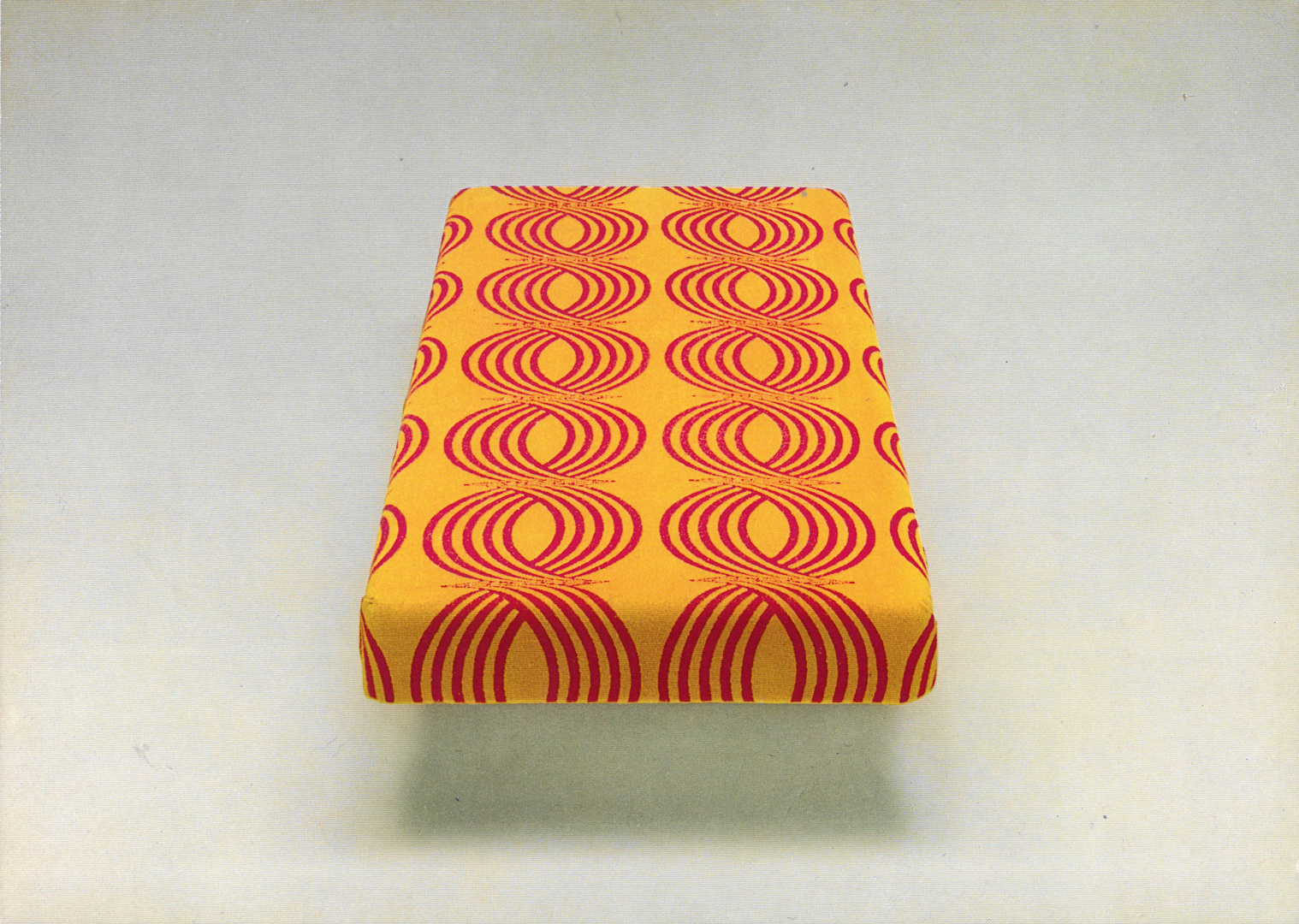

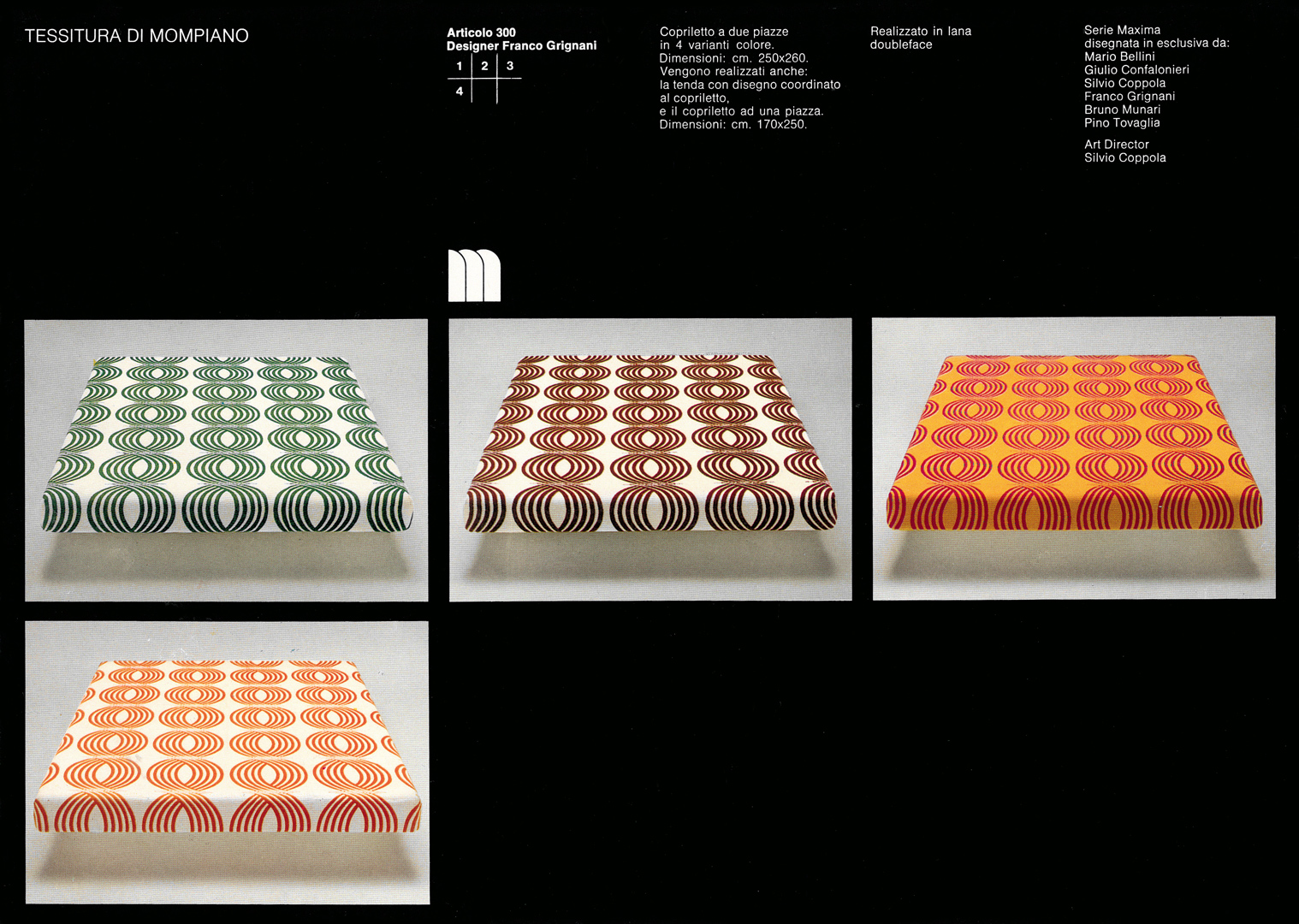

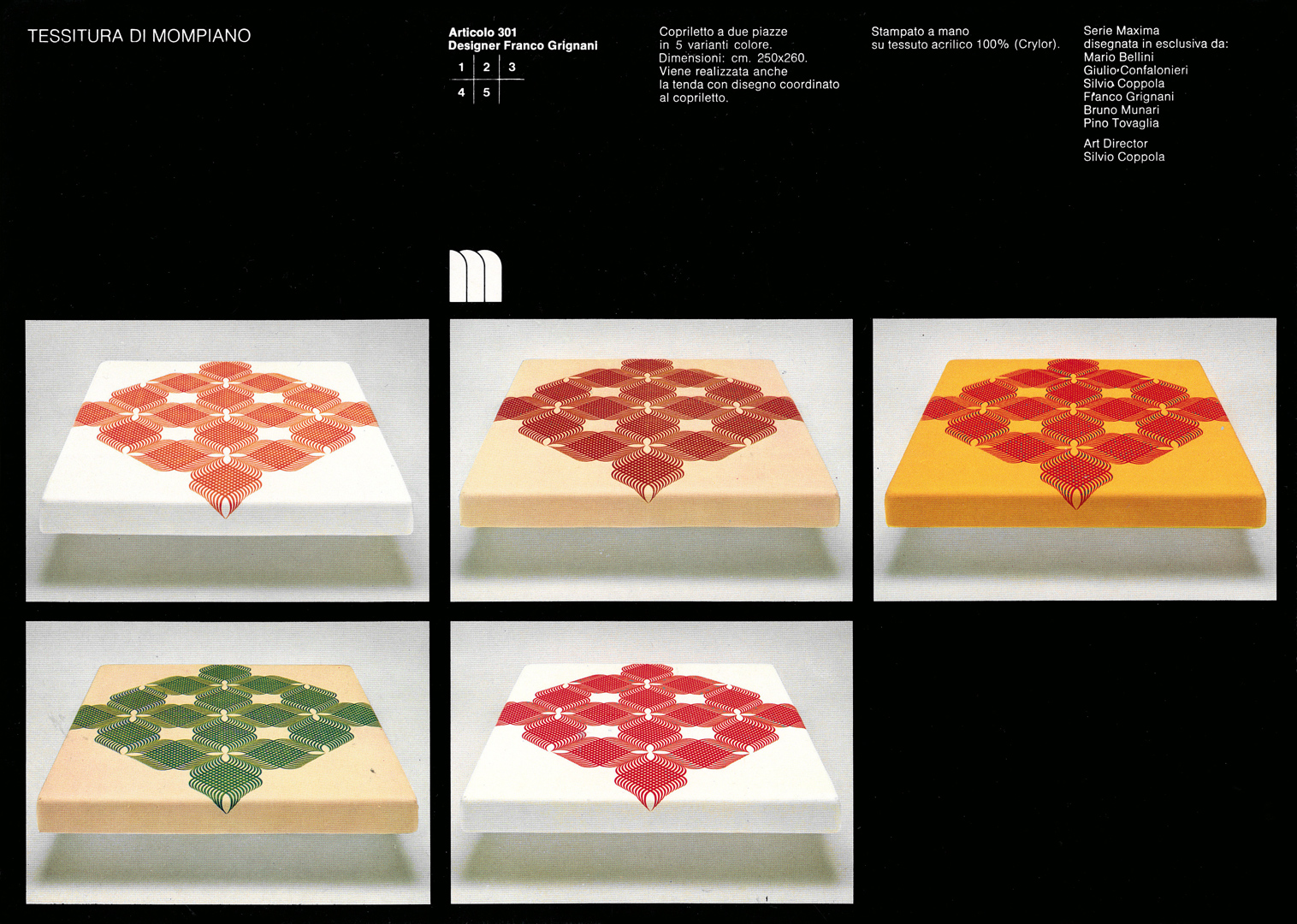

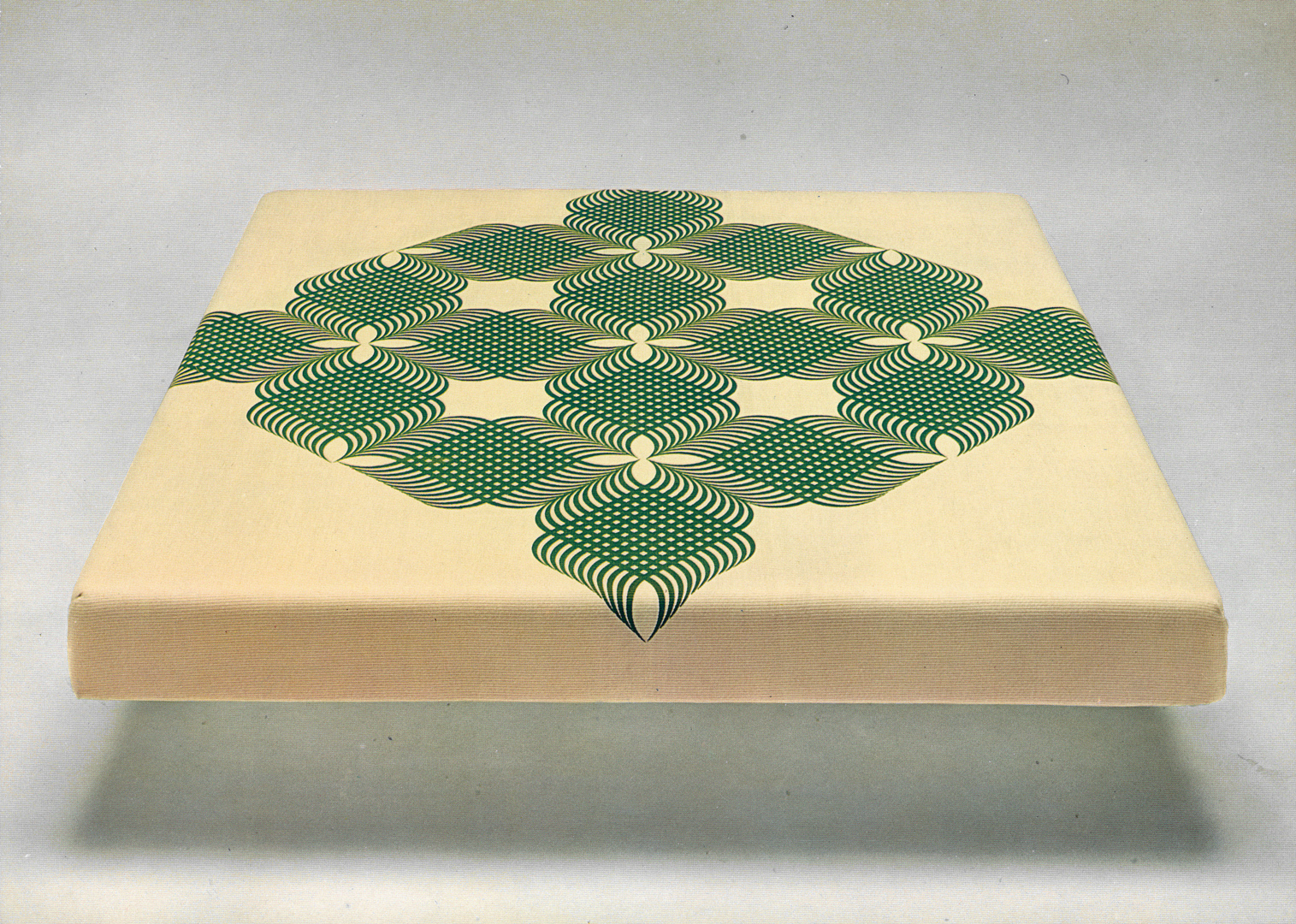

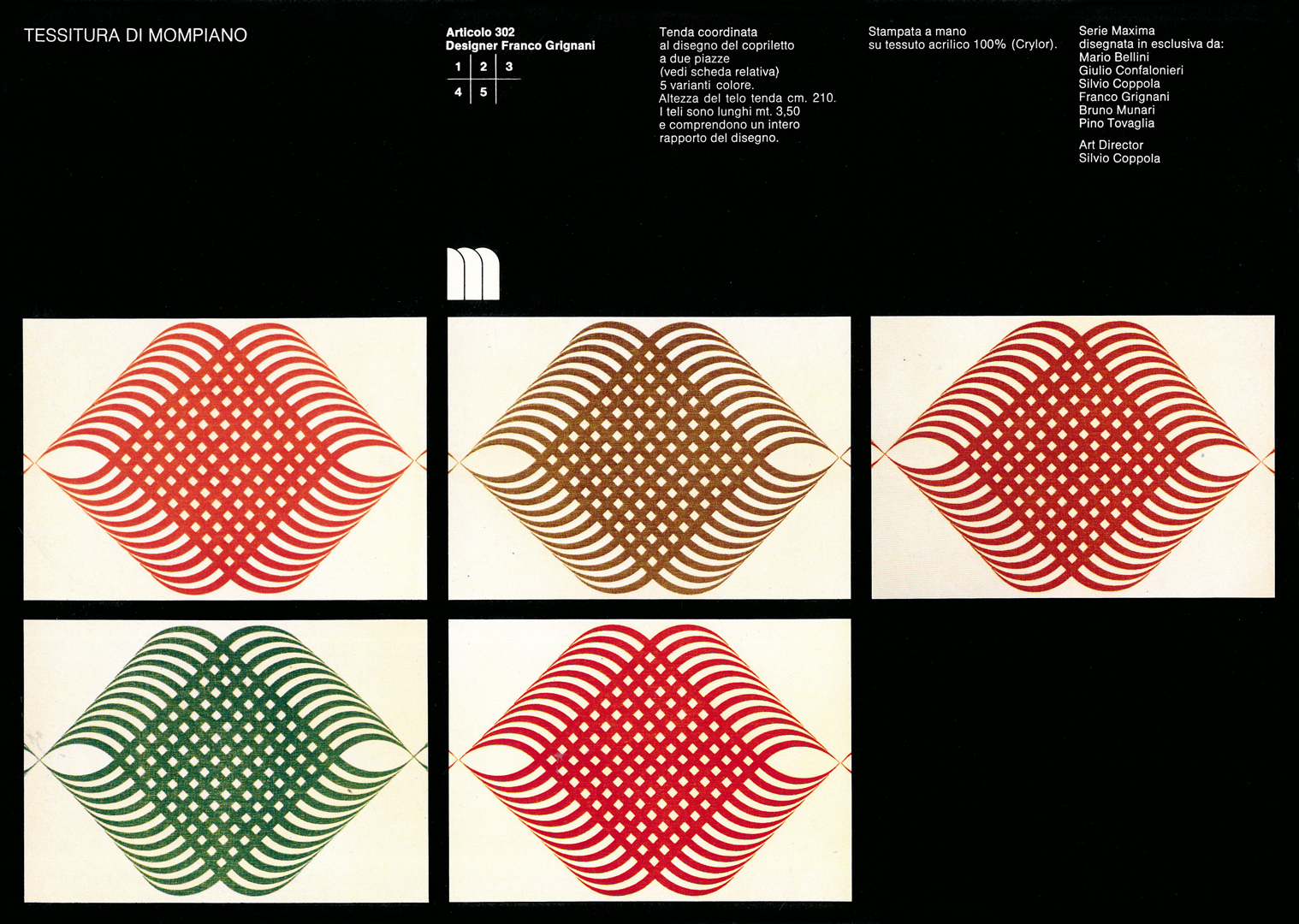

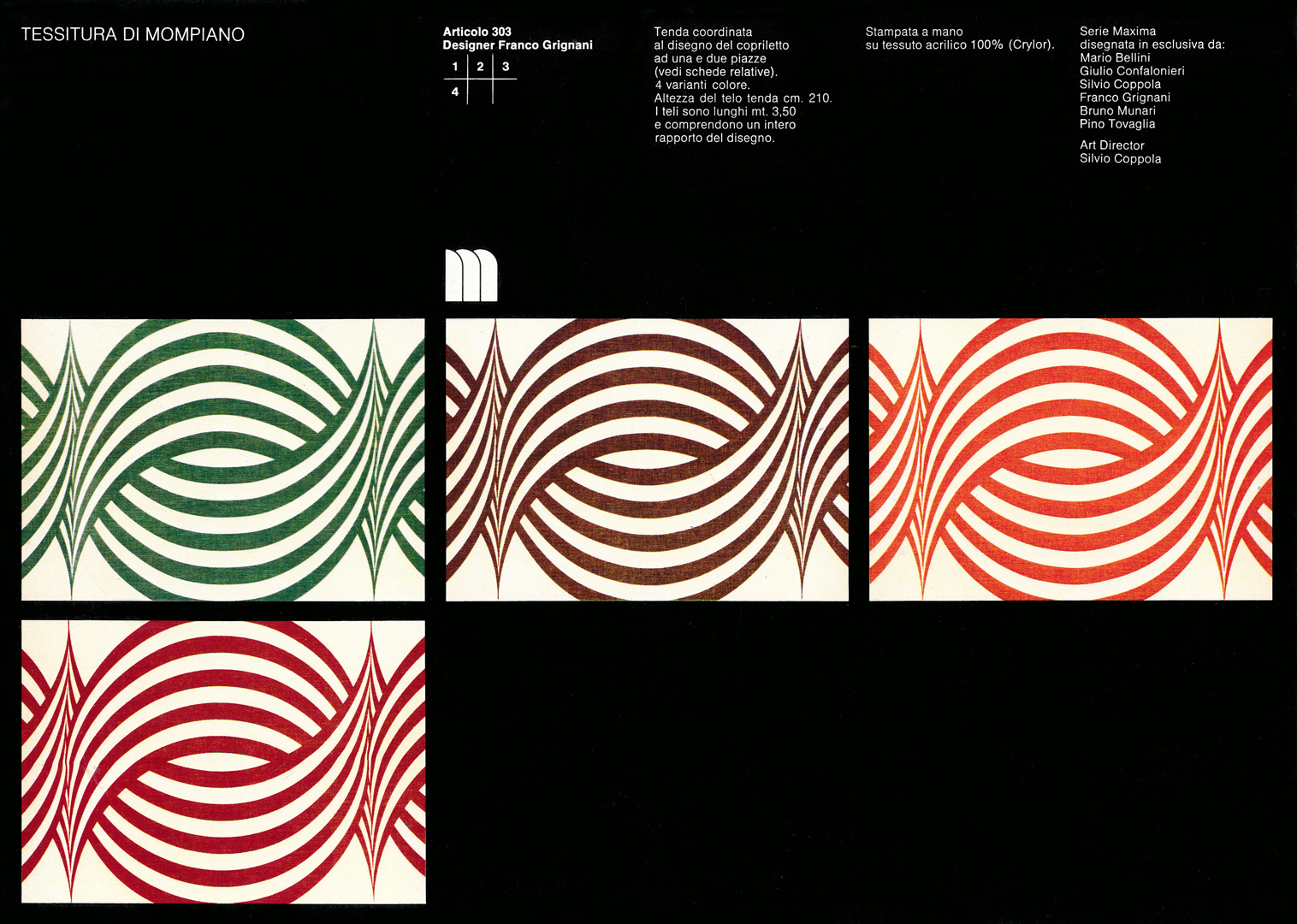

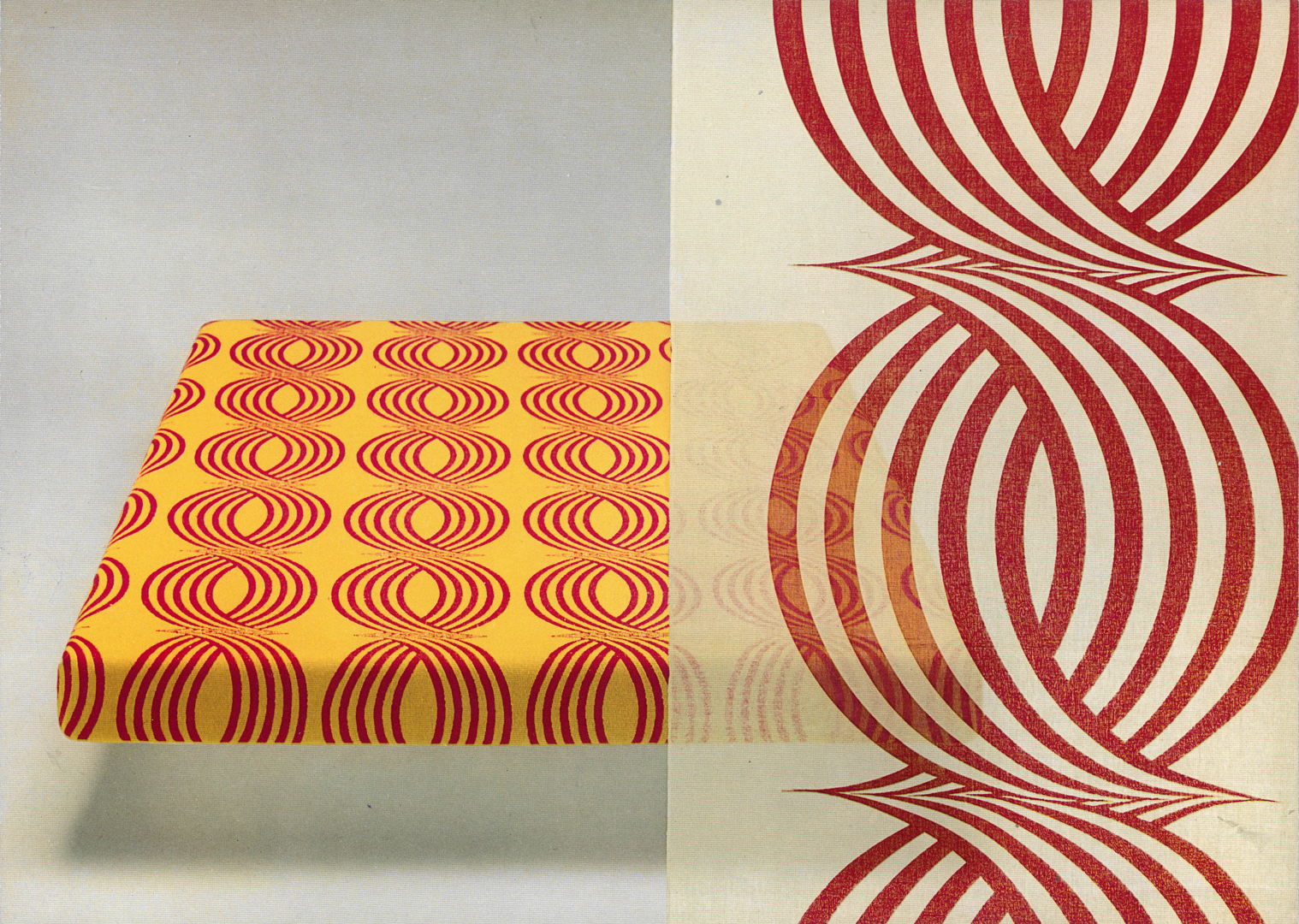

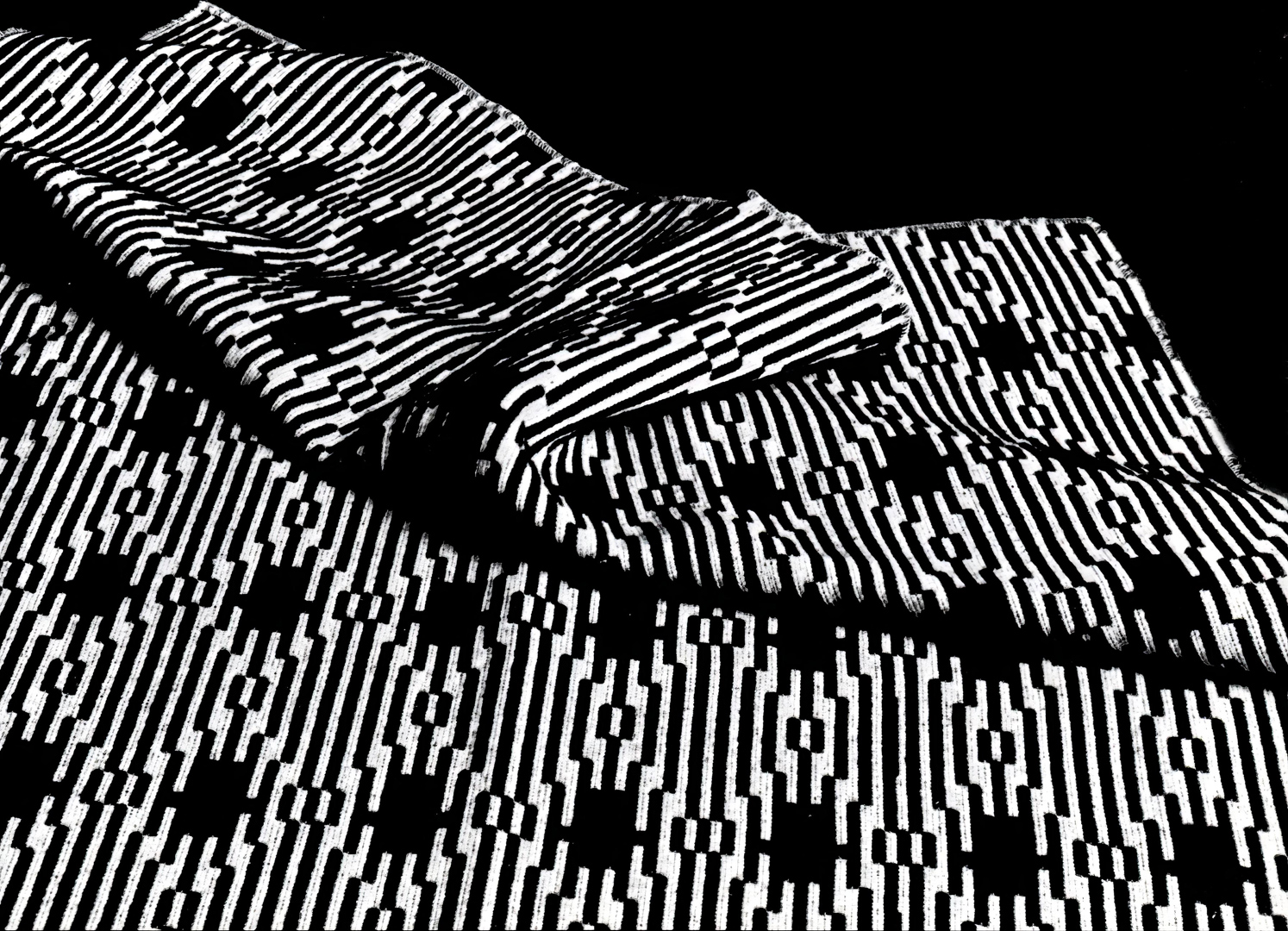

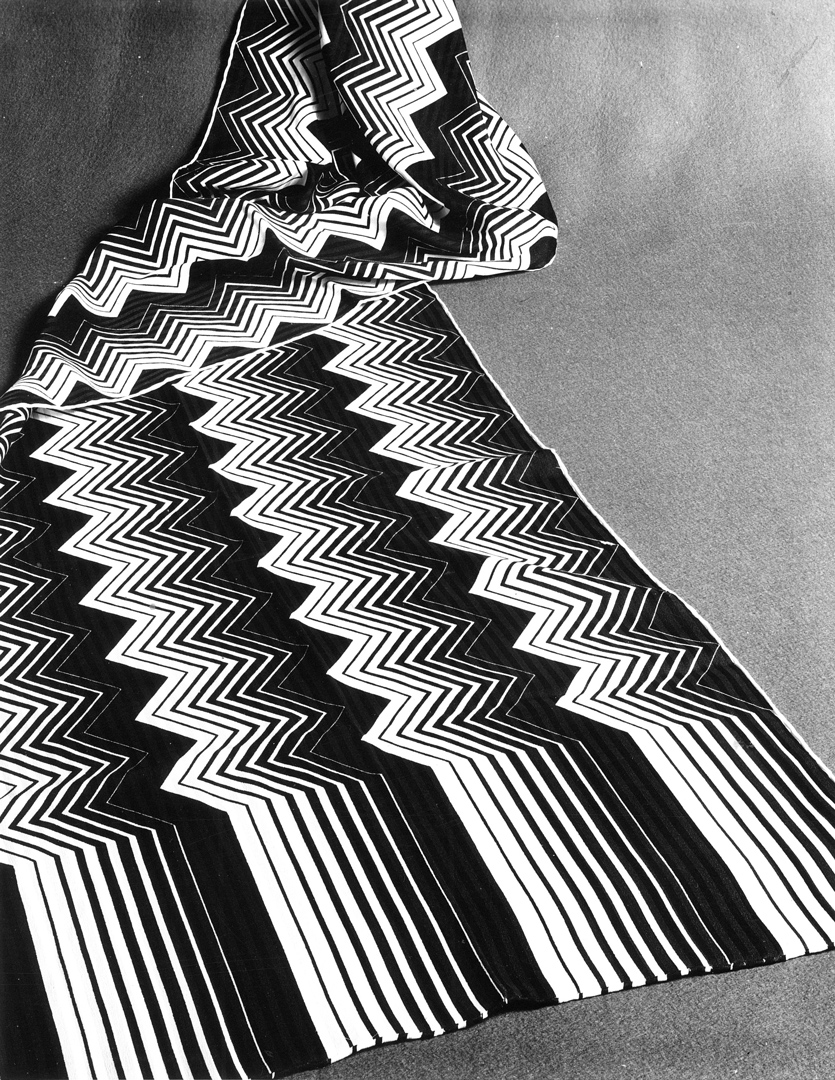

In 1971, the ED Group participated in the M.I.A., the Mostra Internazionale dell’Arredamento (International Furniture Exhibition) in Monza (near Milan), as well as the concurrent Salone del Mobile Italiano (Italian Furniture Expo) at the Milan Fair, presenting ‘signed’ fabrics for blankets, curtains, pillows, and Kakemono for Tessuti Mompiano: “recently some Italian visual designers have decided to operate in the field of furnishing fabrics because these are crucial for the insertion of a certain type of visual message in homes. […] It is the first time in Italy that a homogeneous group of architects and designers, preliminarily coordinated, operates in the field of furnishing fabrics” [from ‘Ottagono’, n° 26, 1972], “completely subverting, in a positive sense, the image of a well-known weaving factory in Brescia” [from ‘Corriere della Sera’, 11/09/1971].

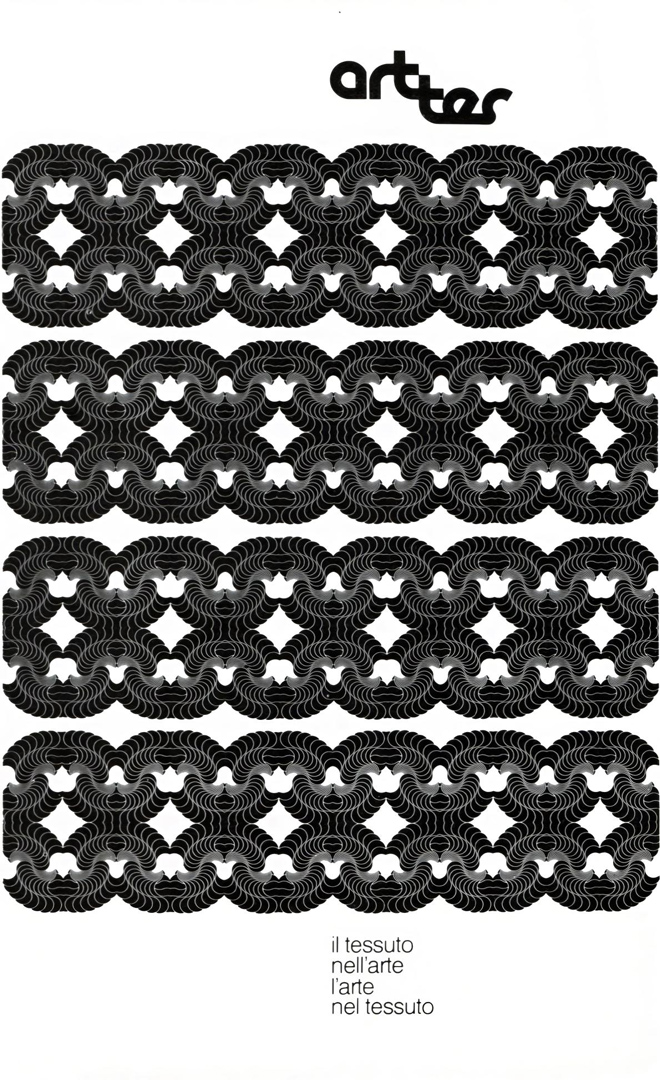

Grignani, Coppola, and Tovaglia also collaborated on a series of curtains called Vistarama for MB in Milan. Additionally, Grignani designed carpets for Montedison in 1973, taking advantage of the dyeability of Meraklon fibre. He also worked on a textile collection for Driade, explaining how his research extended from paper to fabric with a jacquard structure. The design featured an alternating modular iteration, enhanced by the optical effects created by material and color variations in the two yarns used. His understanding of the technical aspects of weaving was evident. The slogan for ‘art-tes’ in 1974 indirectly conveyed the idea: “il tessuto nell’arte / l’arte nel tessuto” (“fabric in art / art in fabric”). Grignani created other designs for Fiorio in Milan as well.

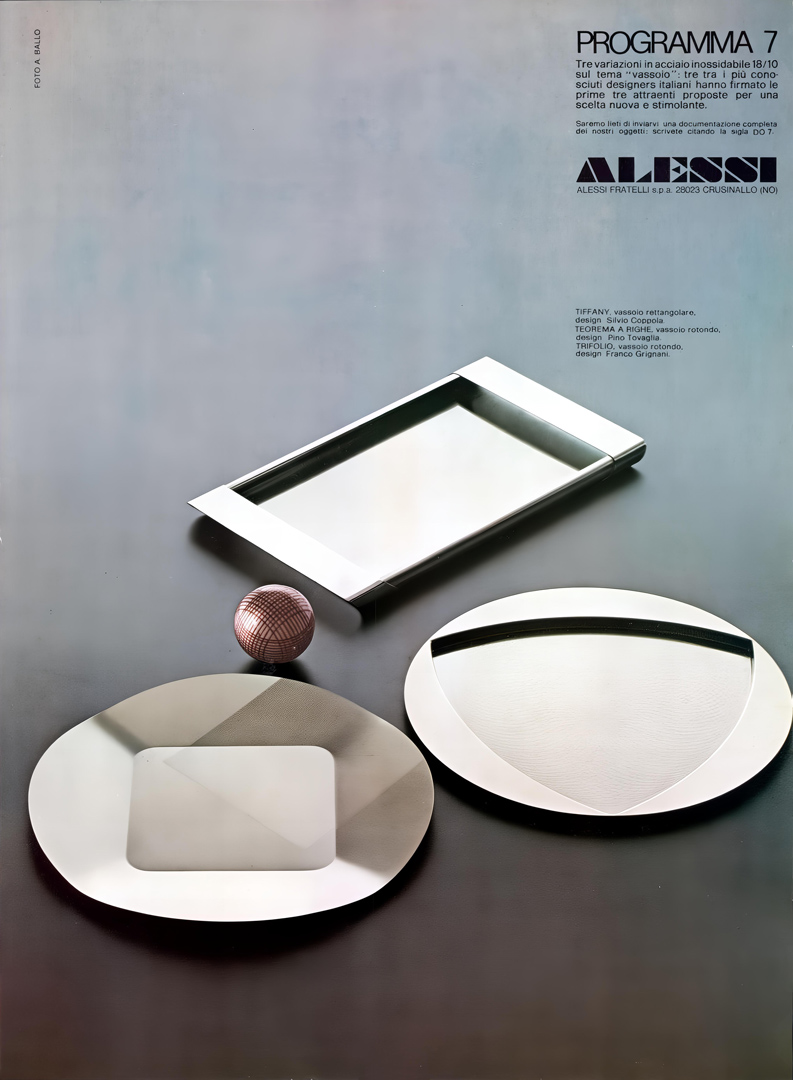

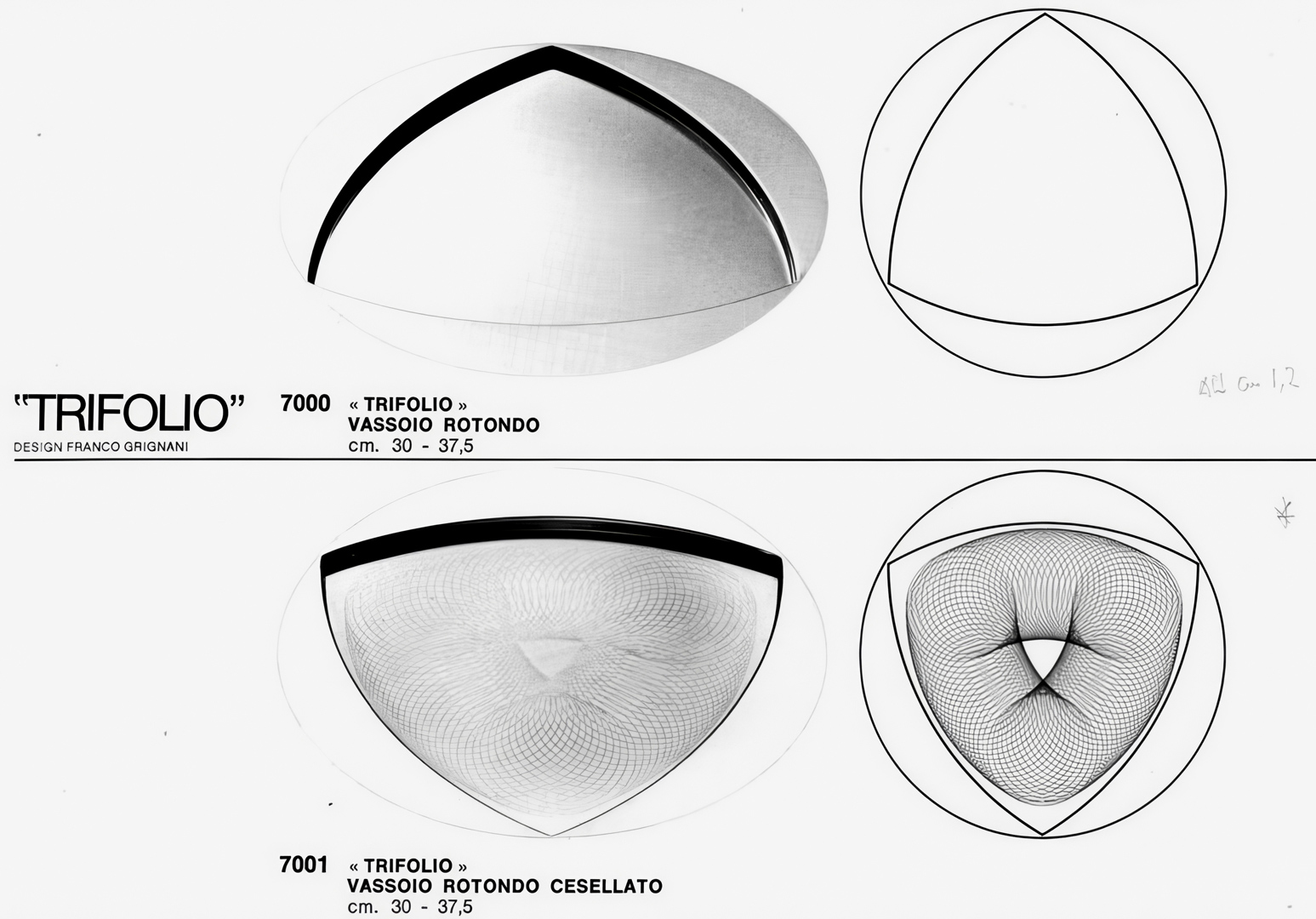

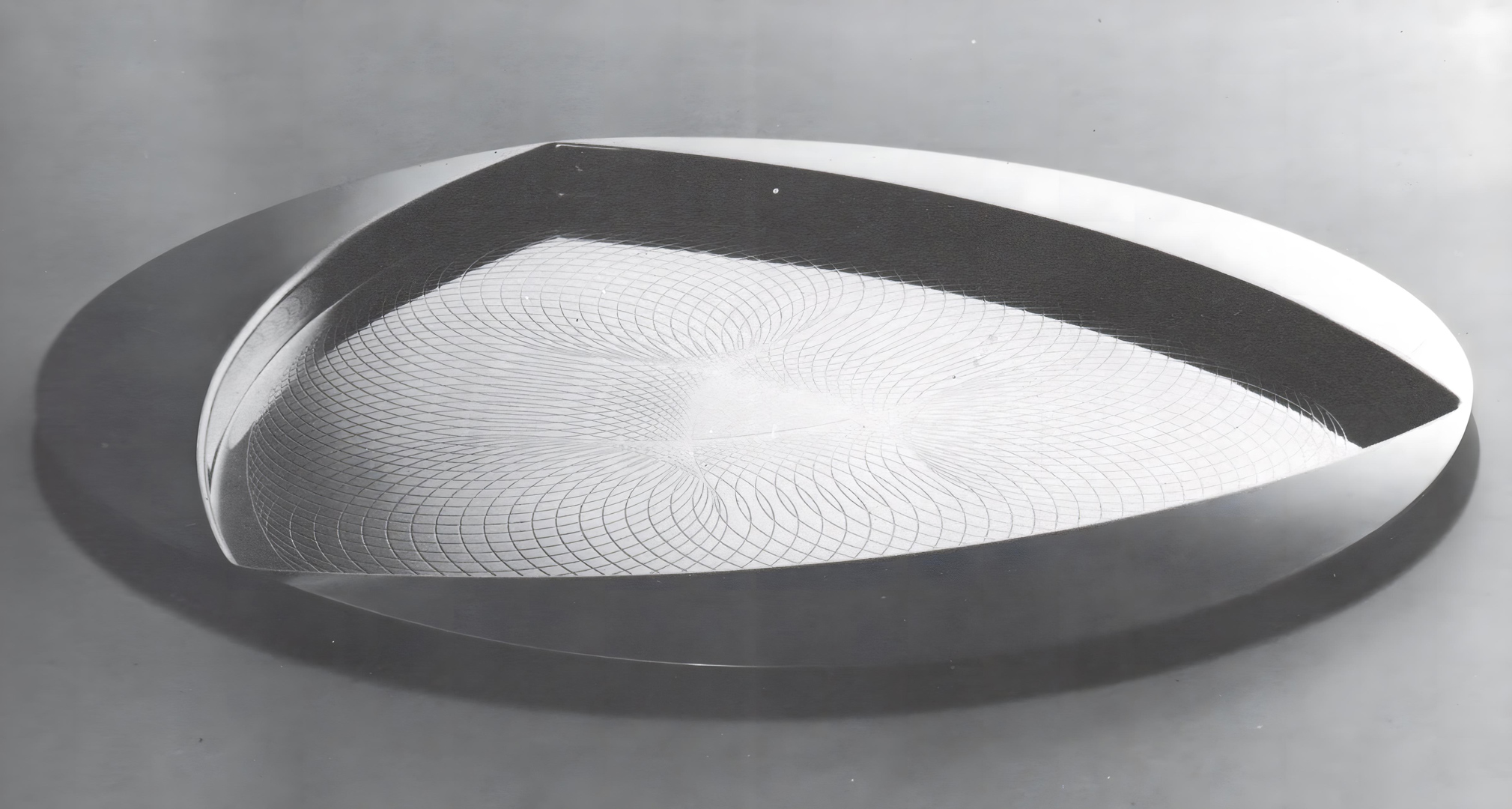

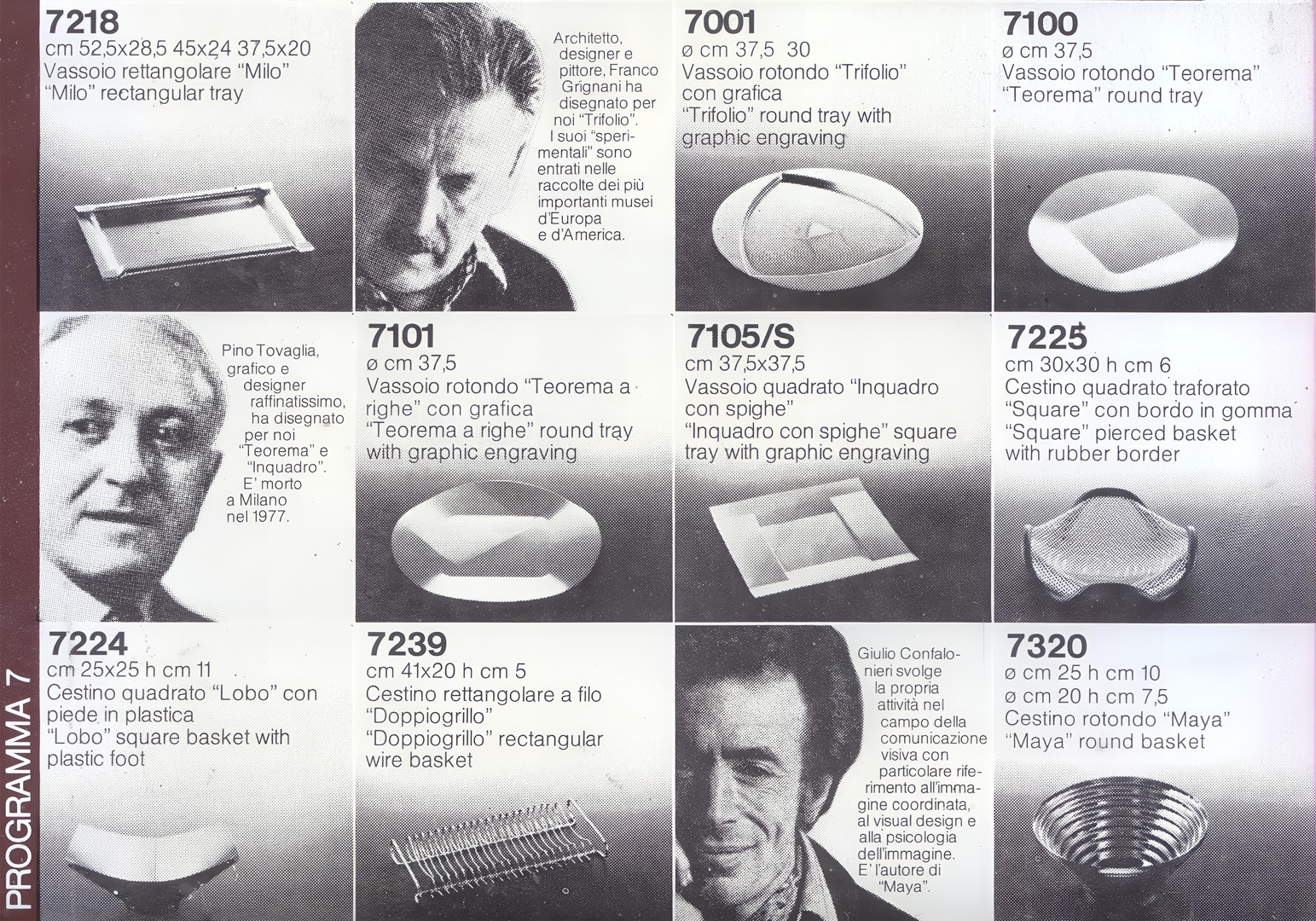

In the early 1970s, Alessi, a company previously focused on traditional and classic gift items, commissioned the ED Group to design the Programma 7 collection. The project aimed to make experimental design products more accessible to a broader audience. These projects allowed the group to emphasize the designer’s social responsibility and their role in educating the public, raising the cultural level of demand once again.

At the end of 1974, Programma 7 was introduced to the market, primarily featuring “three variations in 18/10 stainless steel on the theme of the tray”. Grignani, Tovaglia, and Coppola were involved in this project:

Grignani, Munari, and Tovaglia also collaborated on the design of engraved silver objects for Bacci in Bologna in 1970: “the new collection presents shapes consistent with the different personalities of the designers involved in the ever-current theme of the representative object of the house” [from an ad in ‘Ottagono’, n ° 17, 1970].

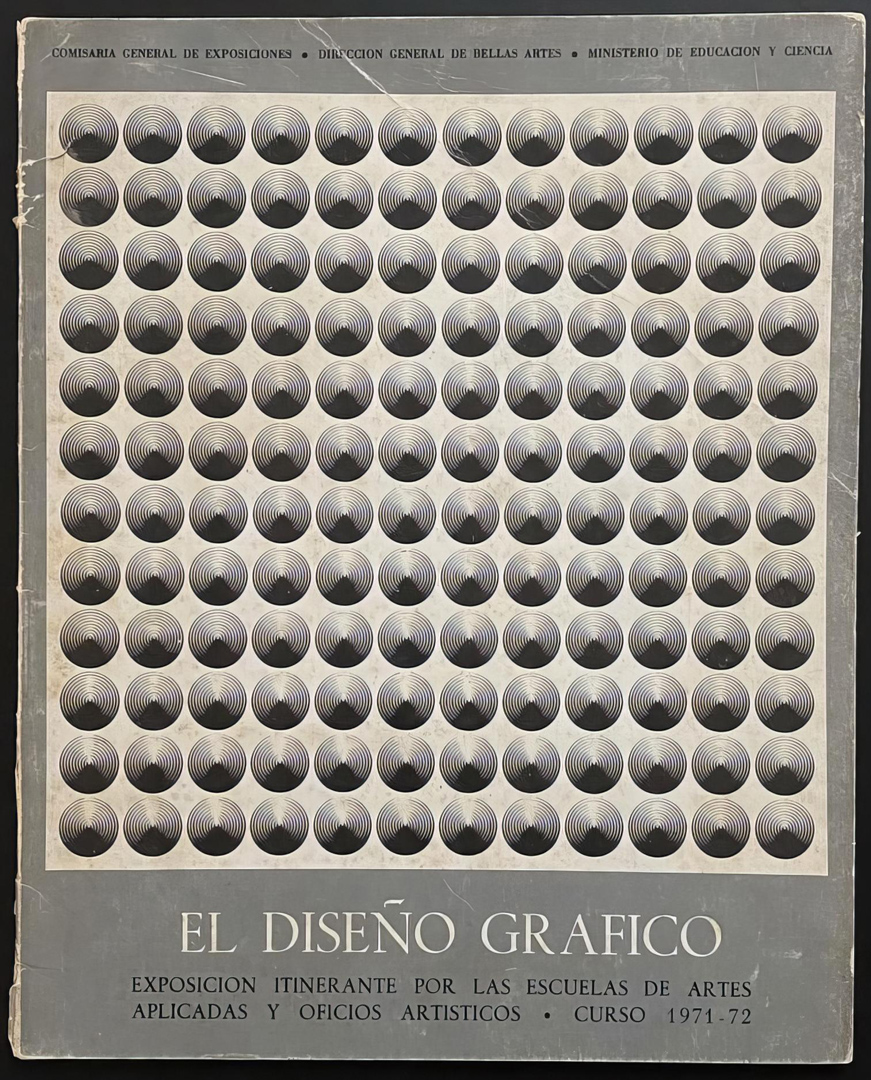

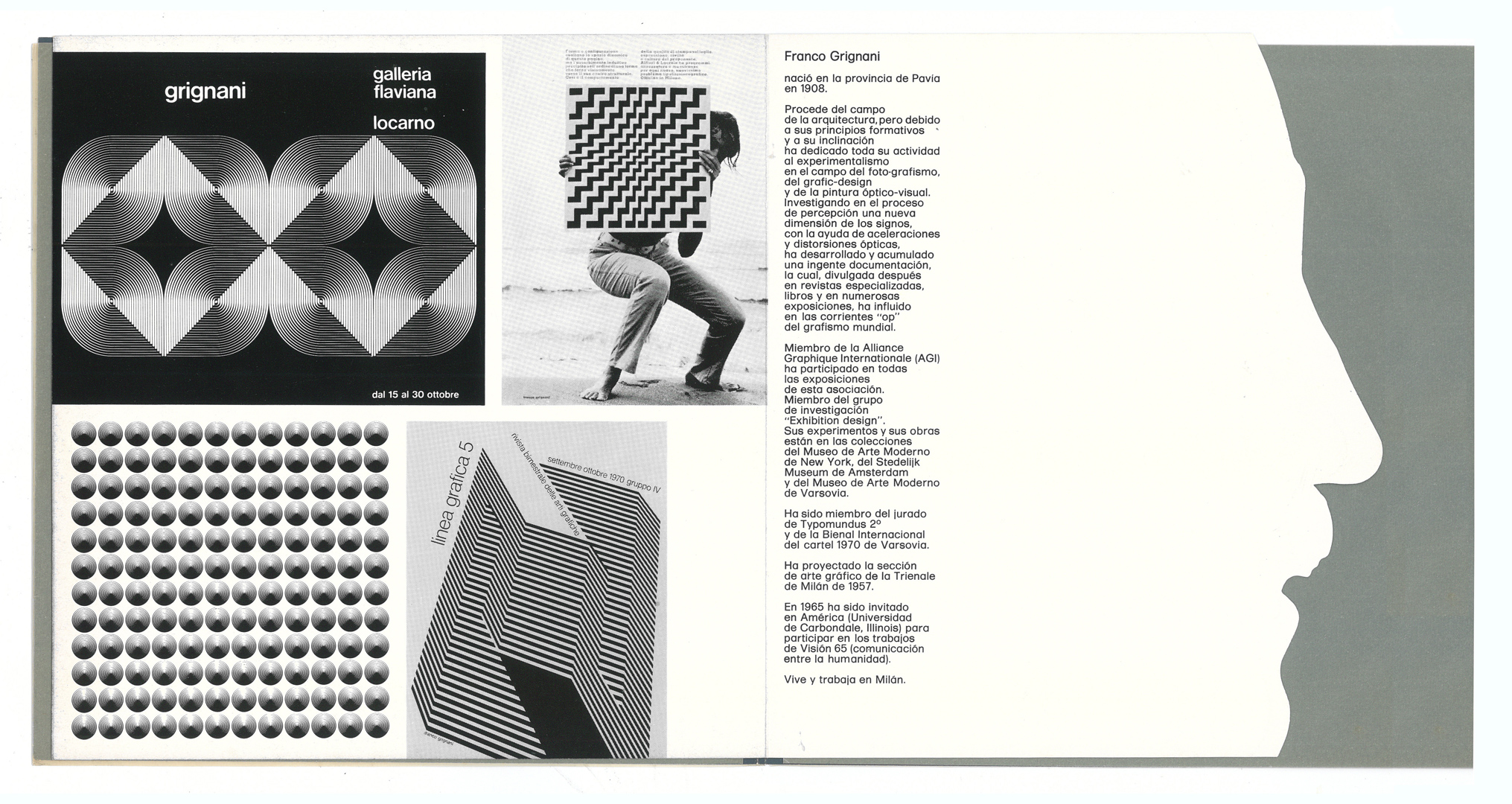

The College of Architects of Barcelona organized a graphic design exhibition in their city, followed by the College of Architects of Seville, which also organized an exhibition. Both exhibitions included public round tables to discuss the problems related to research in visual communication.

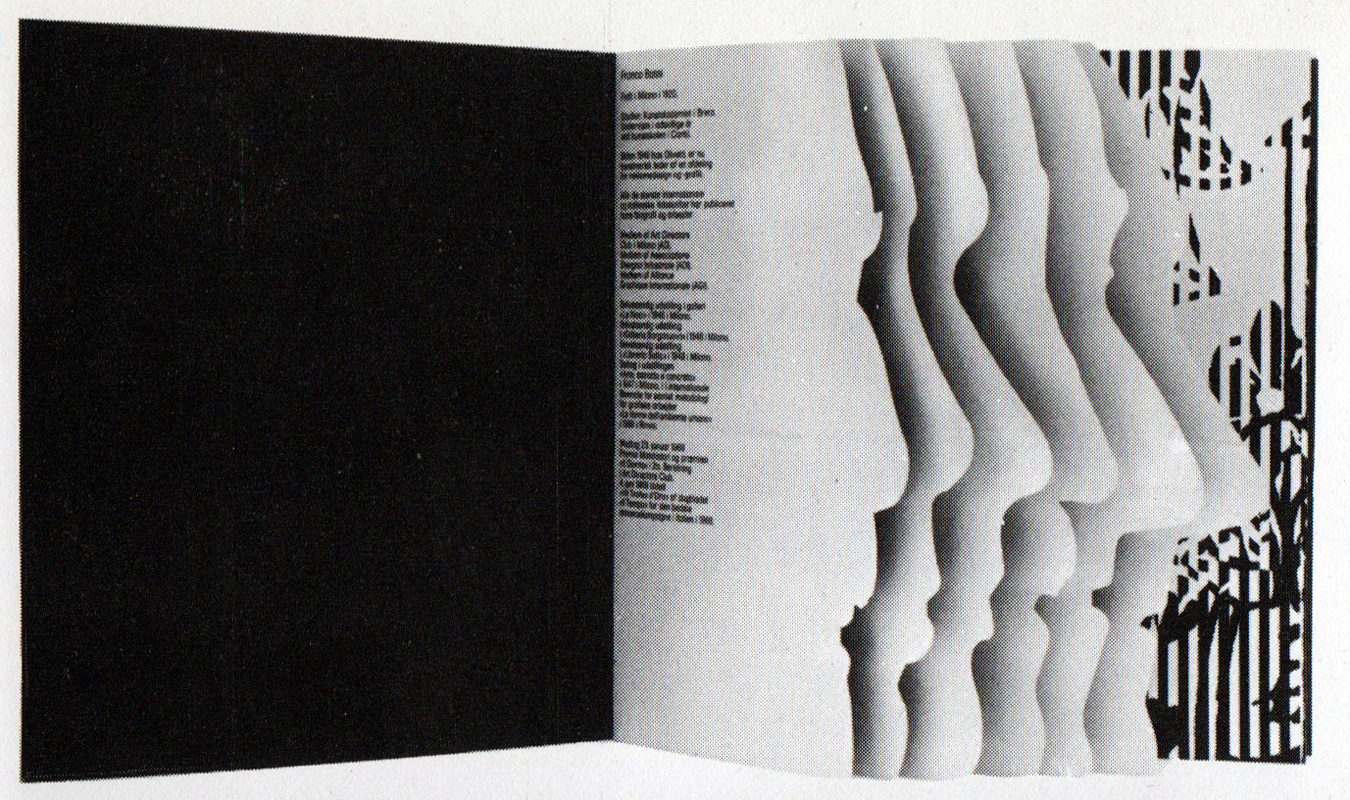

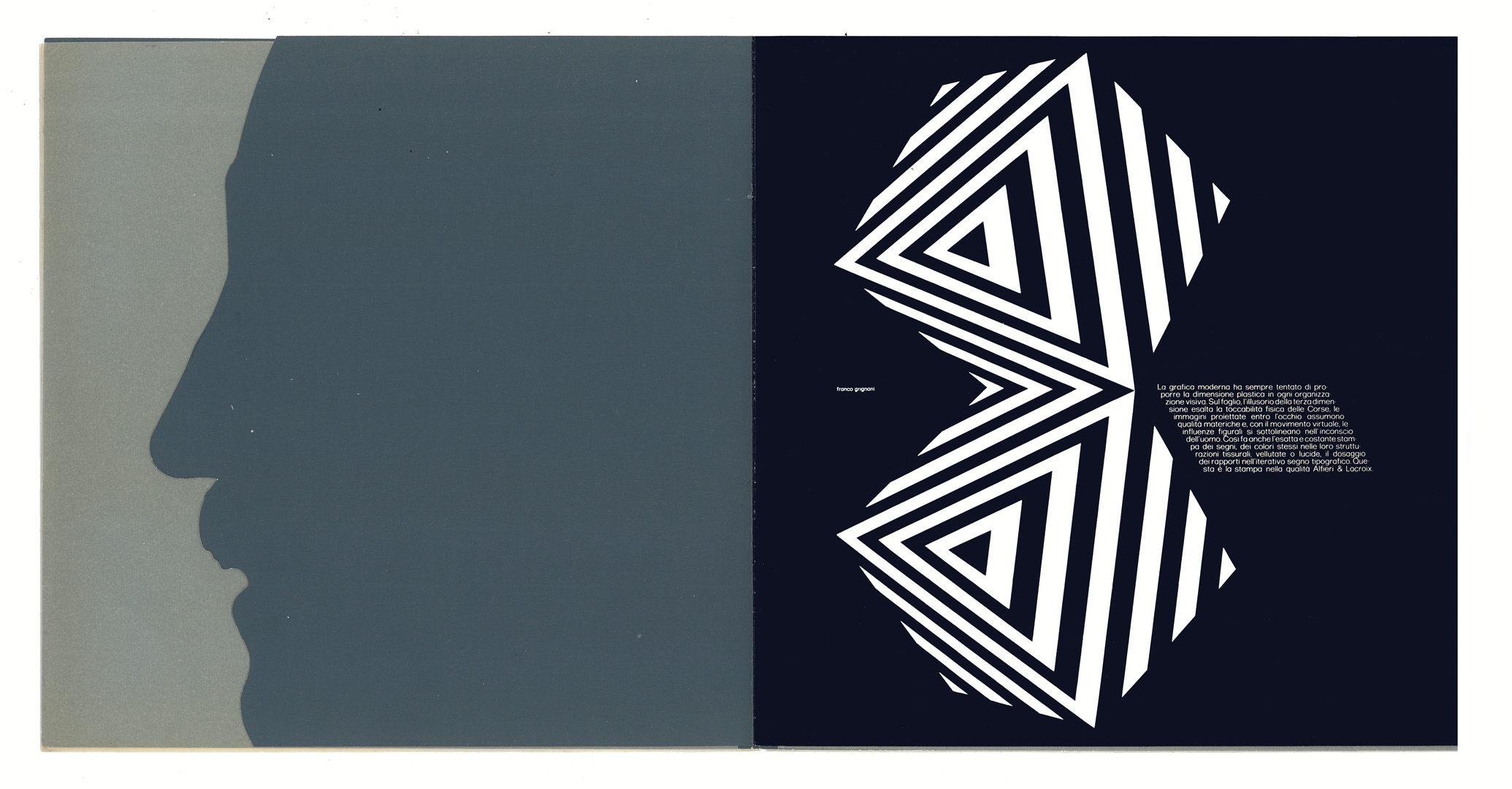

In 1971, Olivetti collaborated with Hispano Olivetti on visual communication exhibitions in Madrid, Barcelona, and Copenhagen (6 graphic designers italianos presentados por Hispano Olivetti). These exhibitions featured members of the group along with Franco Bassi, a graphic designer from Olivetti. The exhibition catalogue was composed of six interchangeable diptychs. Each diptych included the curriculum of each designer, a cut-out profile of their face, and reproductions of some of their designs:

The success of this initiative led to the formation of a new research group, consisting of young Spanish architects and Silvio Coppola, who joined the existing Milan-based group.

“The success of the Milan group is evidenced among others by the numerous invitations, including from the Louvre and some countries of South America, to organize exhibitions of research experiences.”

[from ‘Ottagono’, n° 22, 1971]

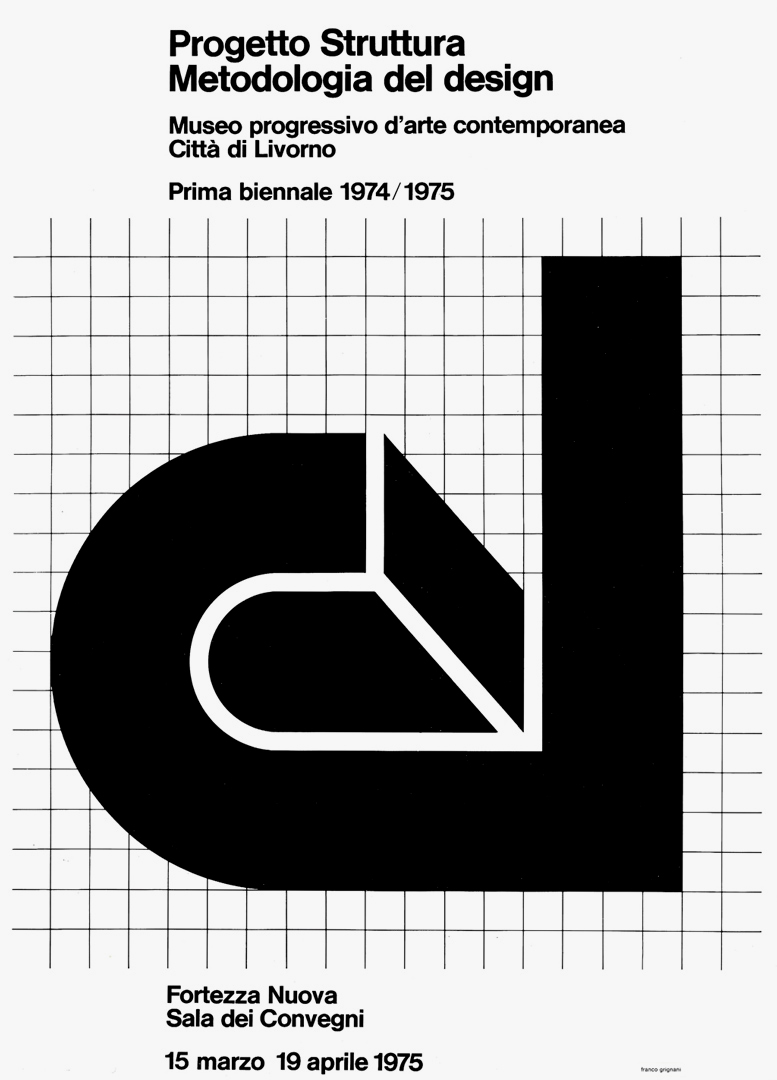

In the spring of 1975, the exhibition Progetto Struttura Metodologia del design (Project Structure Methodology of design) was held as part of the 1st Biennial of Contemporary Art organized by the Progressive Museum of Livorno. This museum was founded in 1974 under the guidance of art critic Lara Vinca Masini (1923-2021), at a time when Italy still had very few contemporary art institutions (its logo is another creation by Grignani: “The d is two-dimensional in the layout, and at the same times becomes three-dimensional to symbolize the product” [r]); the poster of the exhibit was displayed in 1976 at the Warsaw International Poster Biennale. The exhibition showcased thousands of projects and sketches by the six designers of the ED Group. The exhibition’s structure was replicated in the catalogue, which was designed as an educational aid primarily for students. Xerographed copies of the catalogue were provided to students for free upon request.

When the exhibition in Livorno was inaugurated, Franco Grignani had recently concluded a major solo show in Milan, held at the Rotonda della Besana. The catalogue for this exhibition featured a preface by Giulio Carlo Argan, which emphasized Grignani’s prominent role in the visual arts, extending beyond the realm of graphic design. The poster from that Milan exhibition was among the works displayed in Livorno.

The work of the ED collective laboratory, which disbanded around 1976, represented a new paradigm in the dialogue between demand, production, and designers. It offered a concrete reflection on the designer’s role in society, reshaped the exhibition space as a platform for dissemination, sharing, and dialogue, and invested in experimentation.

“Certain things you can never forget.”

Franco Grignani, “Twenty-two years ago”, 1991

[a] ‘Domus’, n° 481, 1969

[b] ‘Ottagono’, n° 15, 1969

[c] ‘Graphis’, n° 145, 1970

[d] ‘Ottagono’, n° 30, 1973

[e] ‘design’, n° 3, 1974

[f] ‘Linea Grafica’, 1, 1973

[g] ‘Linea Grafica’, 3, 1967 (with reference to the 1967 exhibit in Milan, Grattacielo Pirelli)

[h] catalogue of the exhibition “Progetto Struttura Metodologia del design“, 1975

[i] ‘Casa Vougue’, n° 69, May 1977

[l] ‘Ottagono’, n° 26, 1972

[m] Antico Usato, courtesy of Marco Villasmunta

[n] ‘Domus’, n° 540, 1974

[o] courtesy of Jens Müller

[p] ‘Ottagono’, n° 22, 1971

[q] Libreria El Astillero, courtesy of Pablo Capurro Ferrer & Beatriz García Pablos

[r] ‘European Trademark and Logotypes‘, ‘Idea’ special issue, 1979

[4] Museo del Marchio Italiano

[6] GARADINERVI, courtesy of Robert Rebotti

[7] AIAP / CDPG Centro di Documentazione sul Progetto Grafico, courtesy of Lorenzo Grazzani

[11] AIS/Design

[this post is not CC BY-NC 4.0 due to some adaptations from AIS/Design by Michele Galluzzo, based upon the book “Pre design 1969“]

ITA original texts from Grignani, Struttura e decorazione: una scelta della grafica, ‘Linea Grafica’, n° 1, 1973:

[I]: “[…] a mio modo di vedere, la pubblicità, dove è arrivata oggi, emargina la grafica. La pubblicità è diventata descrizione, opera cioè un atto descrittivo per provocare determinati stimoli. La grafica, dove ancora interviene, è solo per suscitare delle zone di particolare interesse visivo, ma non è più così in evidenza, così determinante nella composizione pubblicitaria, dove invece l’immagine, soprattutto quella fotografica, è diventata preminente. La grafica è oggi più utile altrove. […] la grande grafica oggi cammina col design.”

[II]: “Questo pavimento ha componibilità a struttura chiaroscurata e servendosi della visione prospettica propone illusori effetti plastico-dinamici.”

[III]: “La diffusione del decorativo acquista crescente risonanza con l’avvento della macchina. La spiegazione è che essenzialmente la macchina favorisce la creazione di un ripetitivo in senso decorativo. Pensiamo al settore tessile, alla produzione ceramica ecc.”

Last Updated on 18/01/2025 by Emiliano