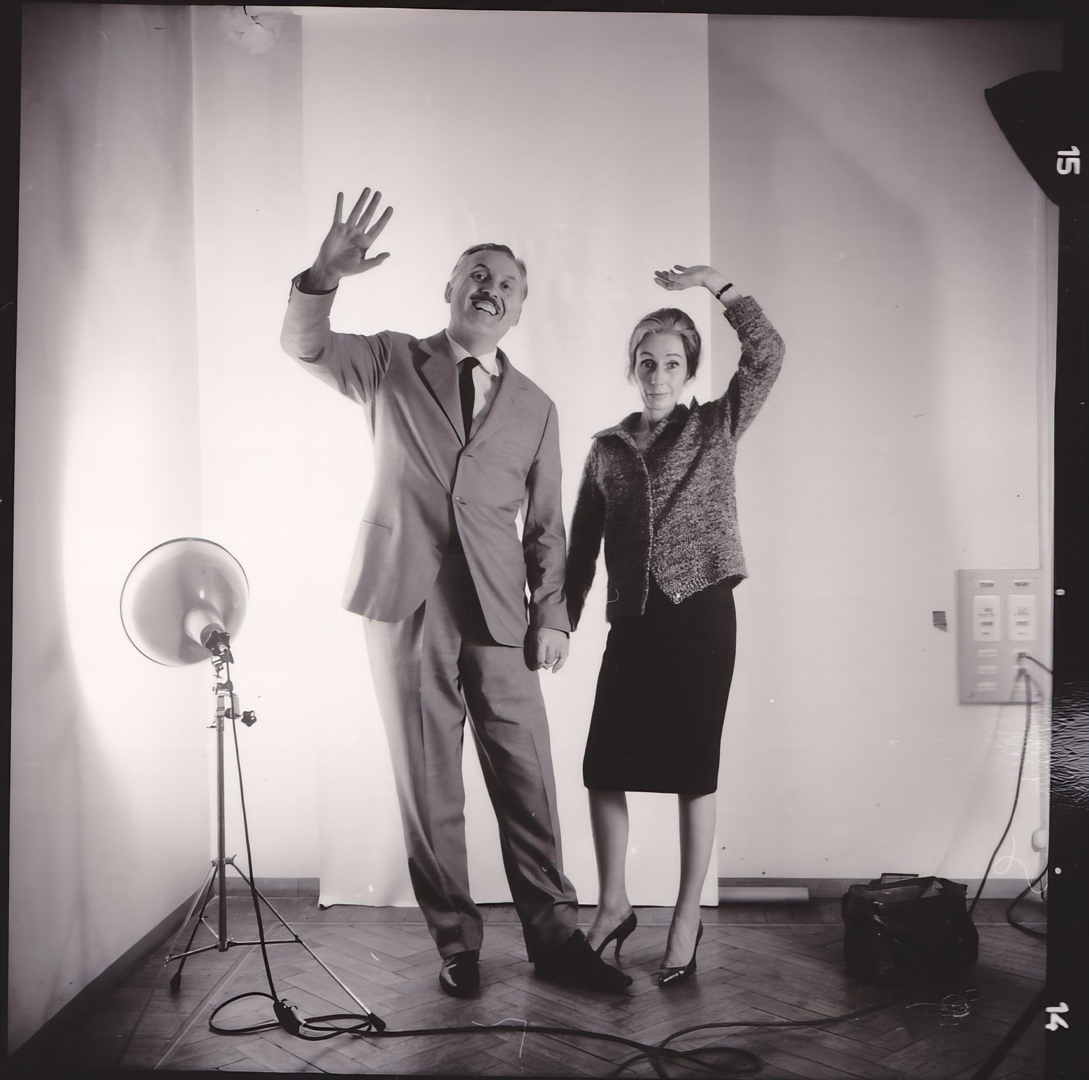

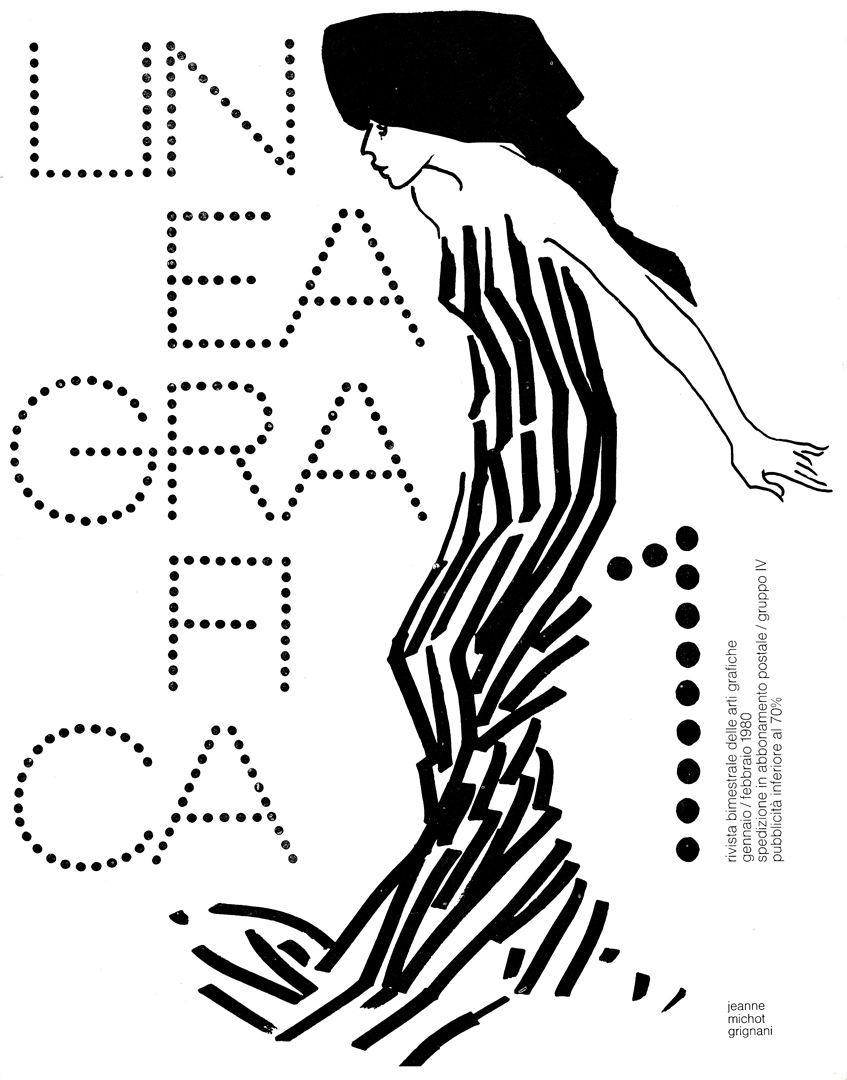

Jeanne Grignani, originally born Jeanne Michot, was ‘the great woman behind the great man’.

Behind her shyness, she possessed a remarkable and strong personality.

Born on the first day of spring in 1916 in Melitopol, near Odessa, Ukraine, Jeanne’s father served as a professor of French literature at the Imperial Lyceum of Moscow. With the impending Russian Revolution of 1917 on the horizon, they embarked on a journey out of Russia, departing from the northern port of Murmansk. After enduring a series of adventures through England and France, they eventually found their new home in Italy.

Jeanne was fluent in French and went on translating Chekhov from the original, while listening to Tchaikovsky and Musorgskij, till her last days. It wasn’t until 1995 that I began to explore her ancestry, and it’s only recently that I discovered her family’s noble roots in French Brittany. Interestingly, Jeanne herself remained unaware of this fascinating heritage throughout her lifetime.

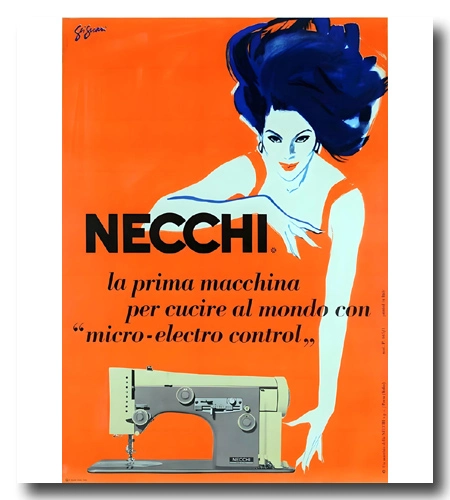

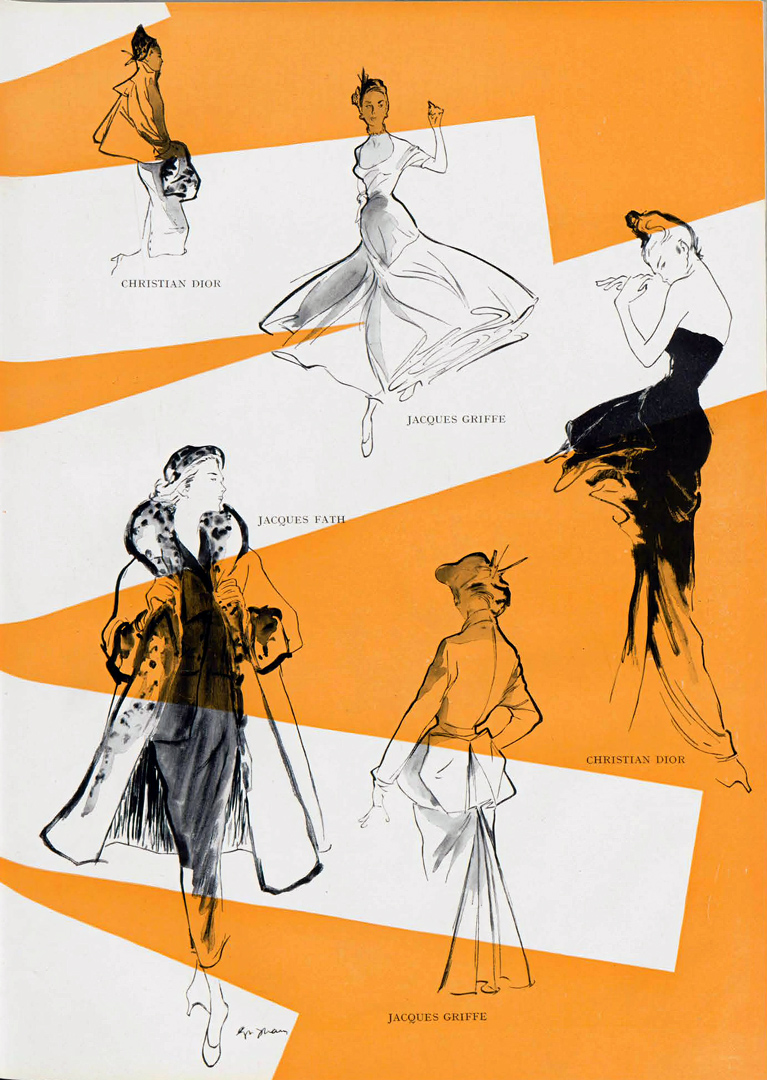

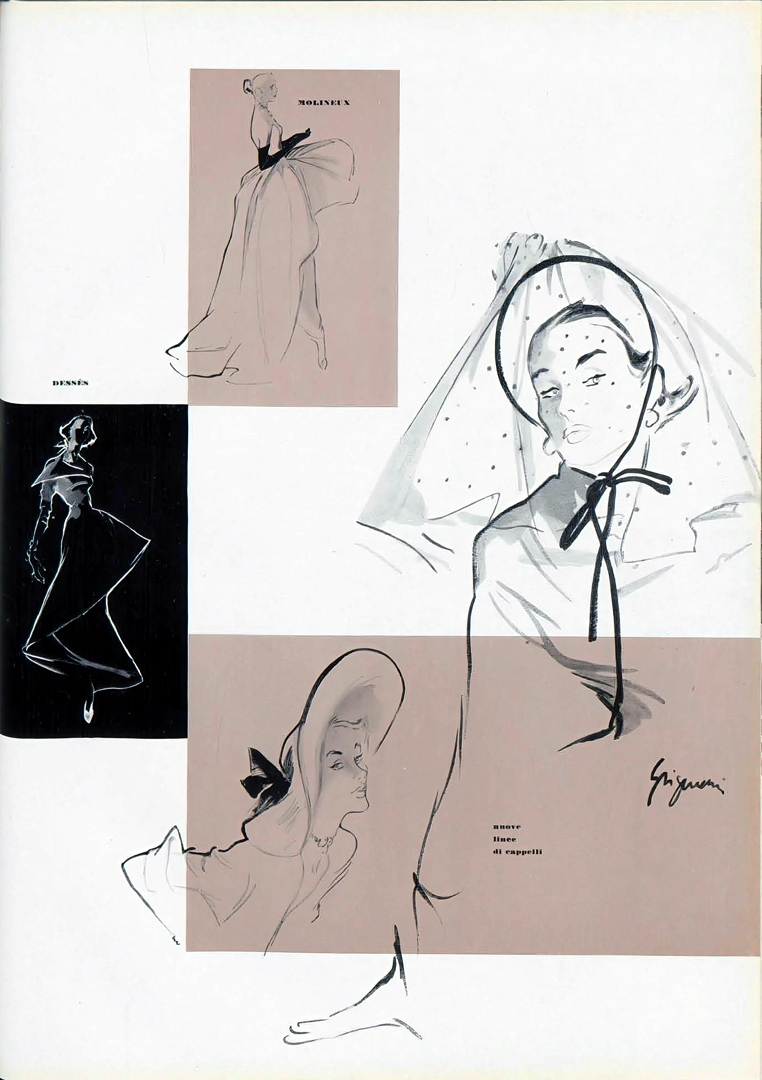

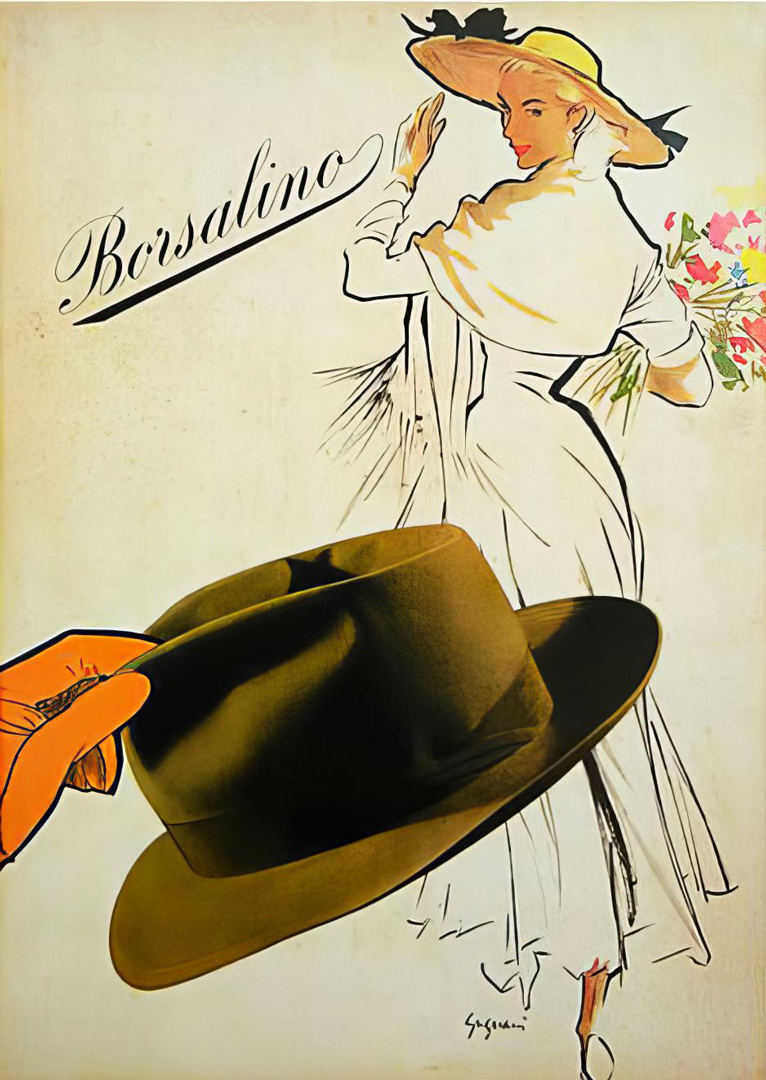

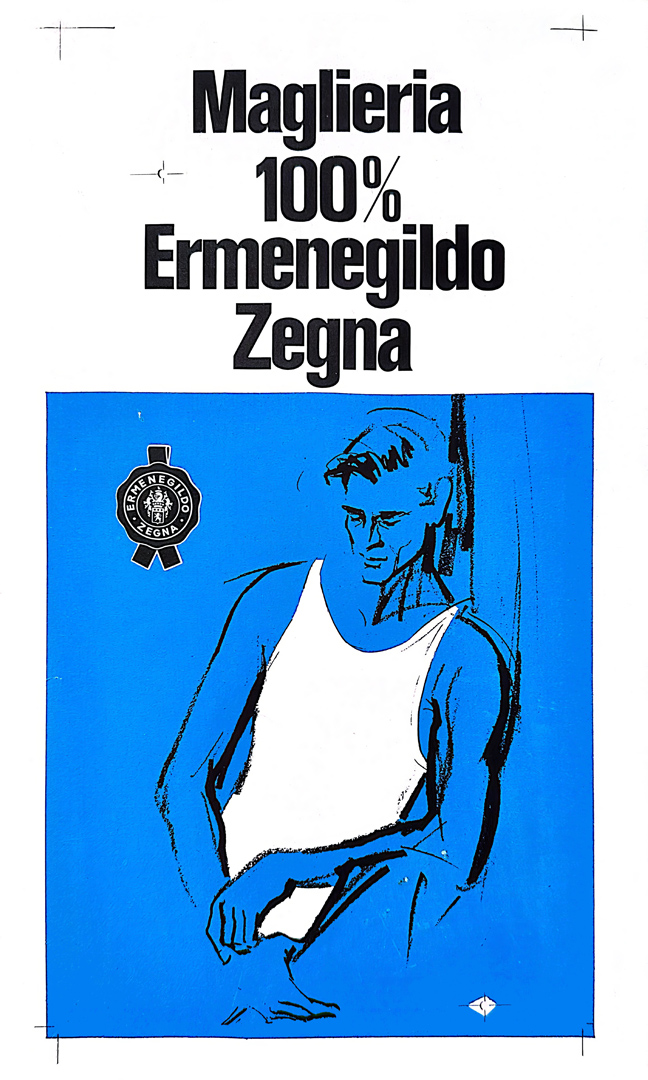

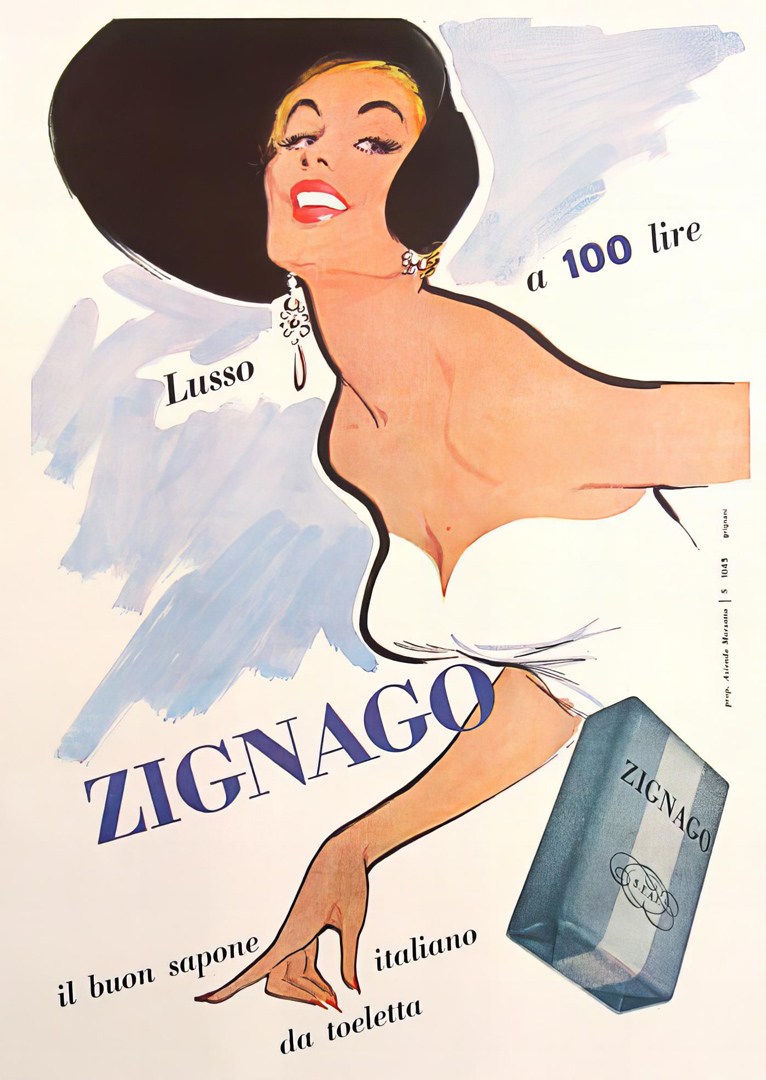

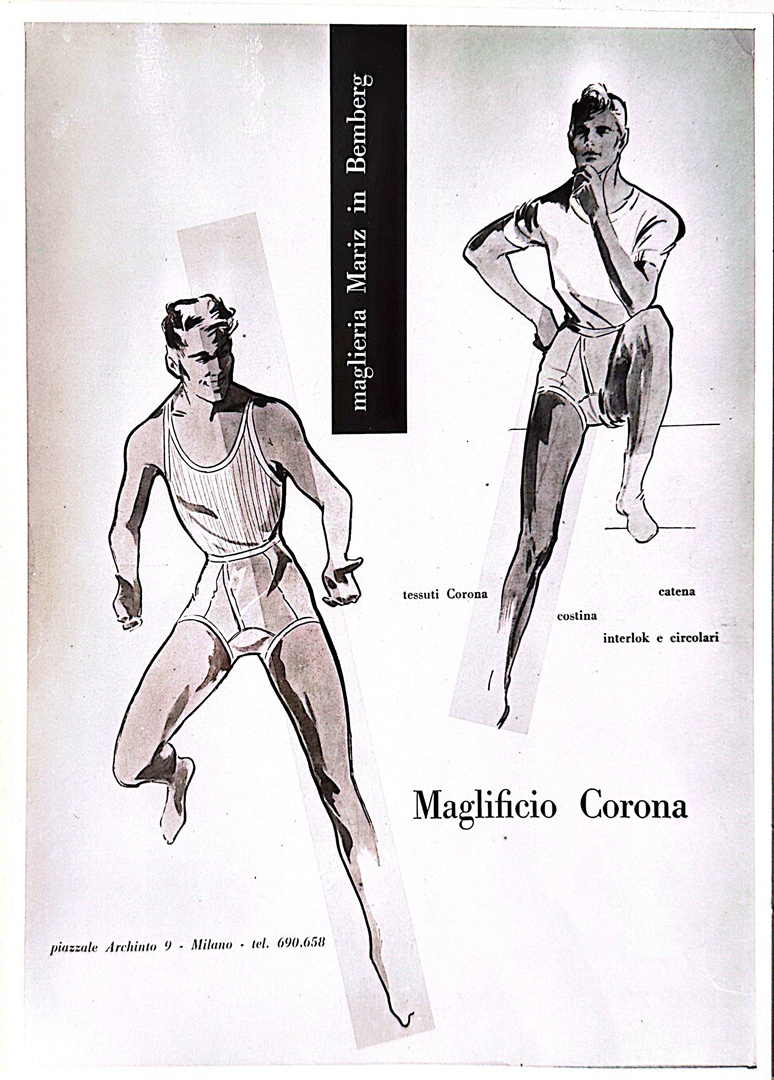

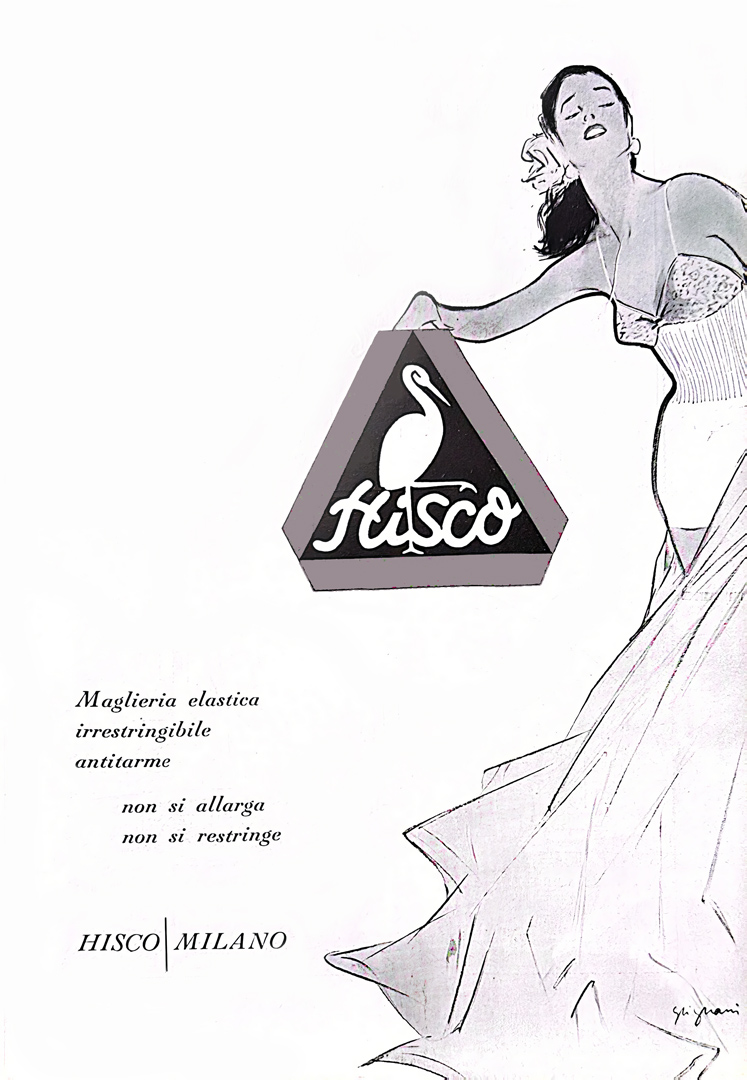

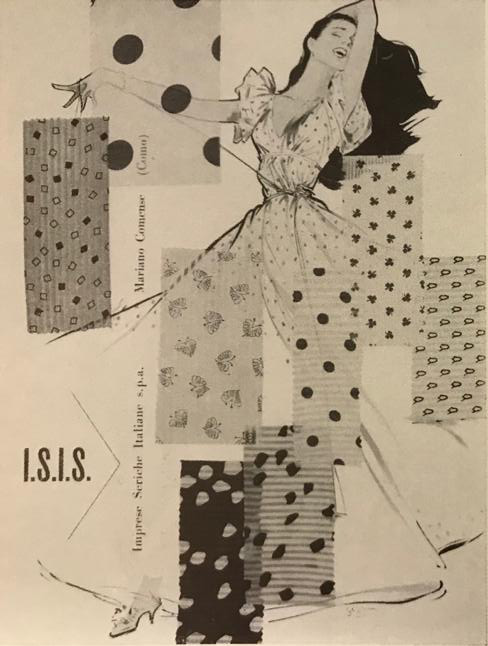

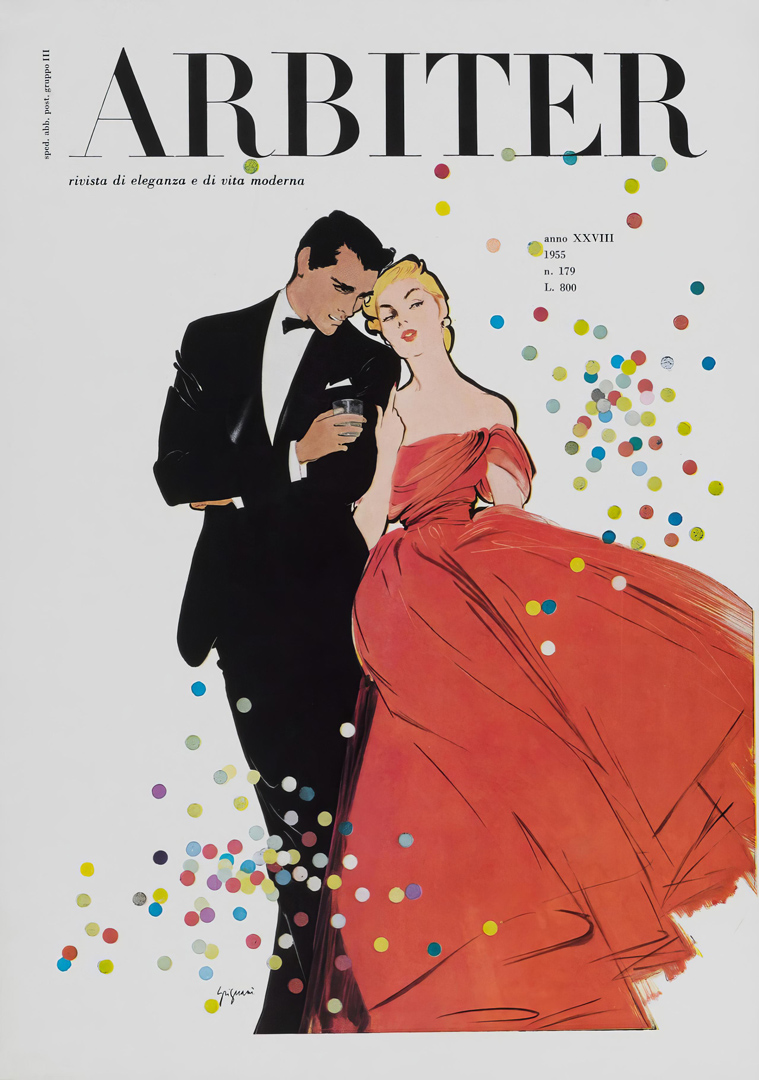

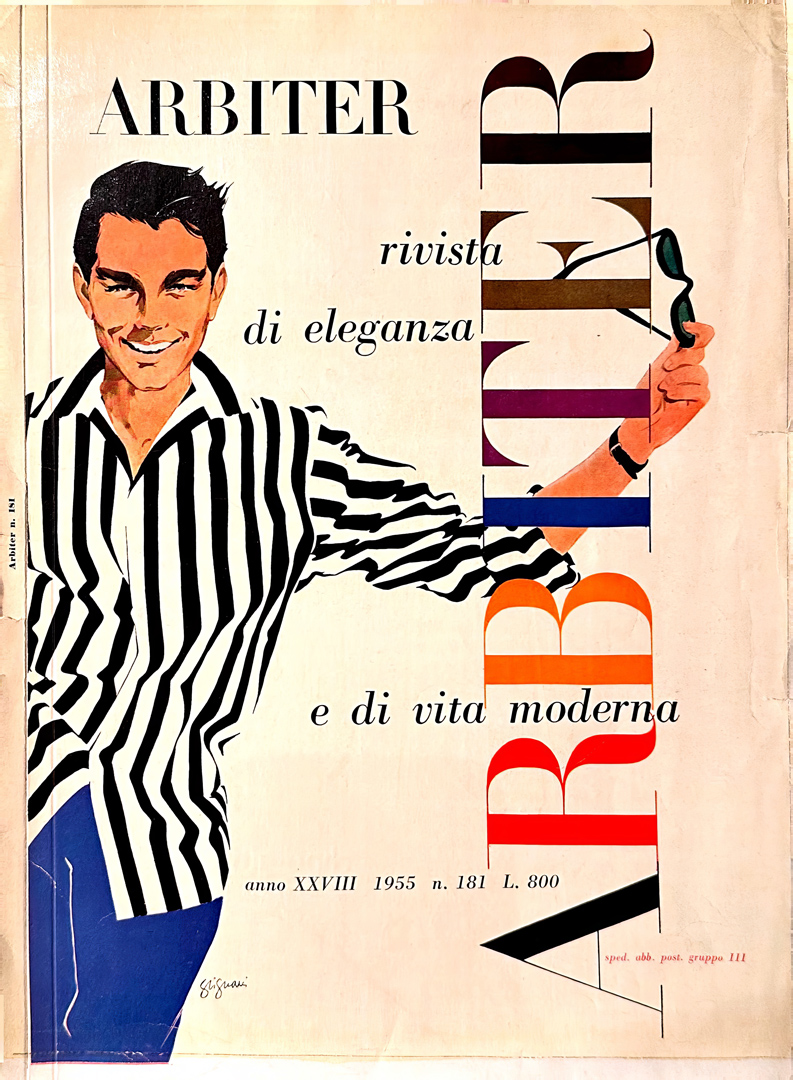

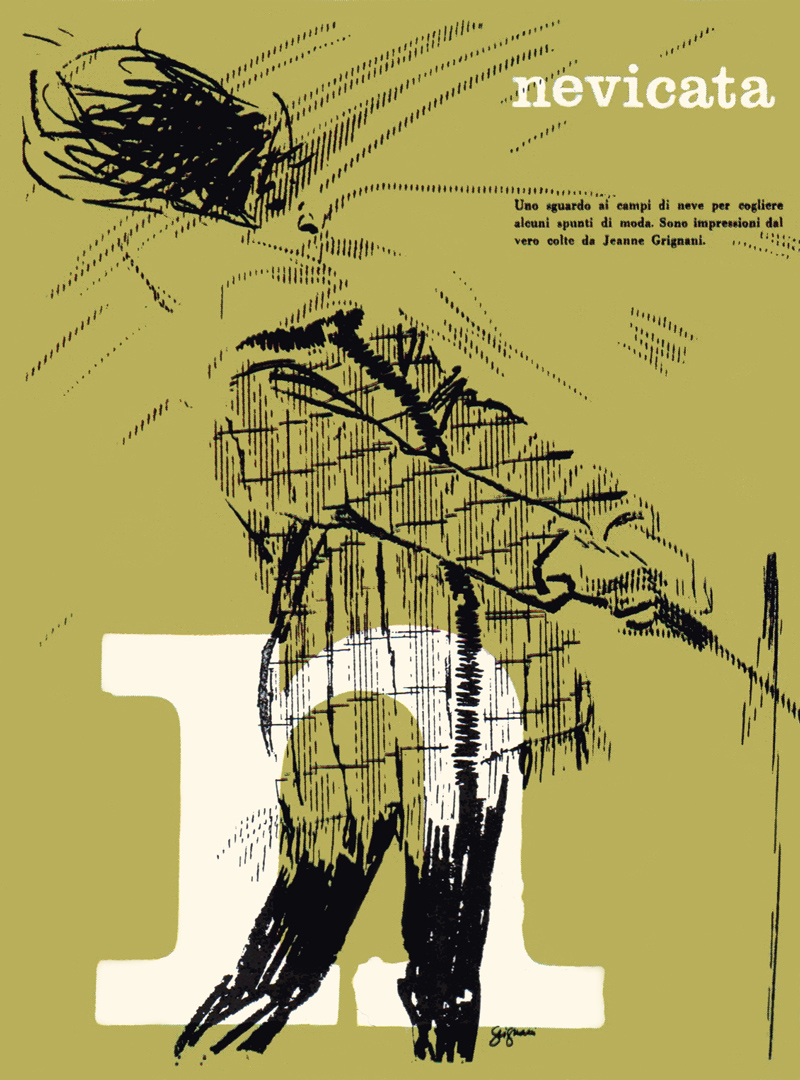

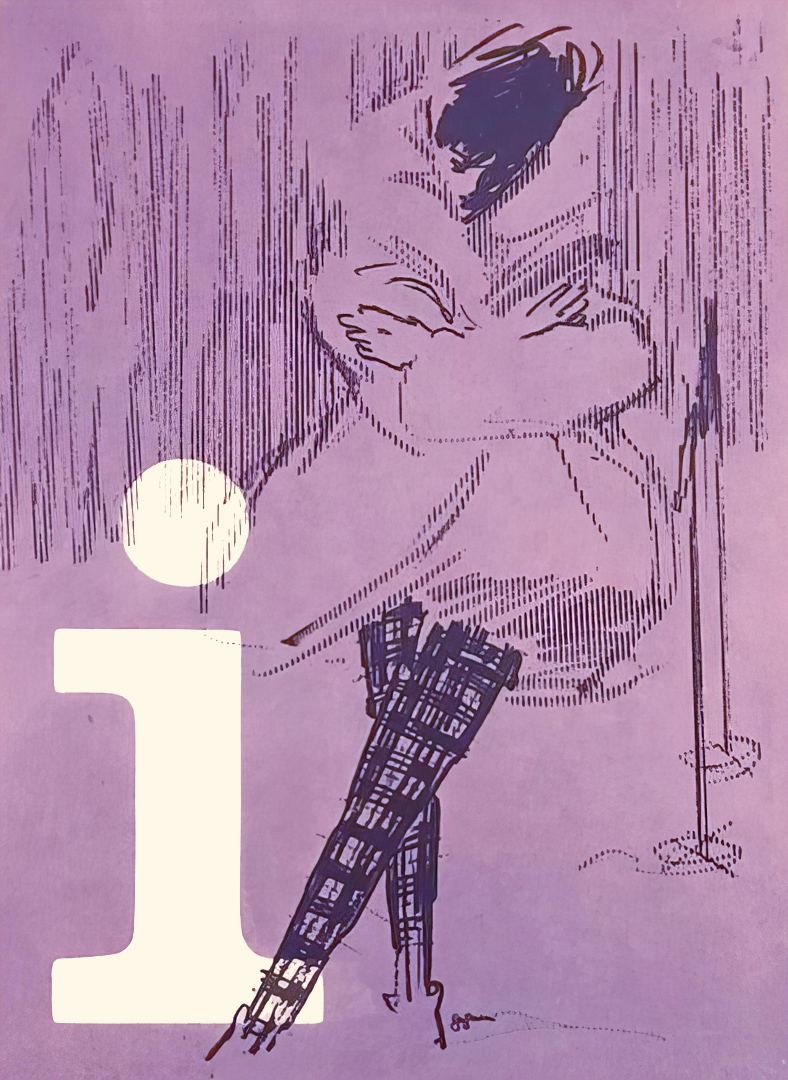

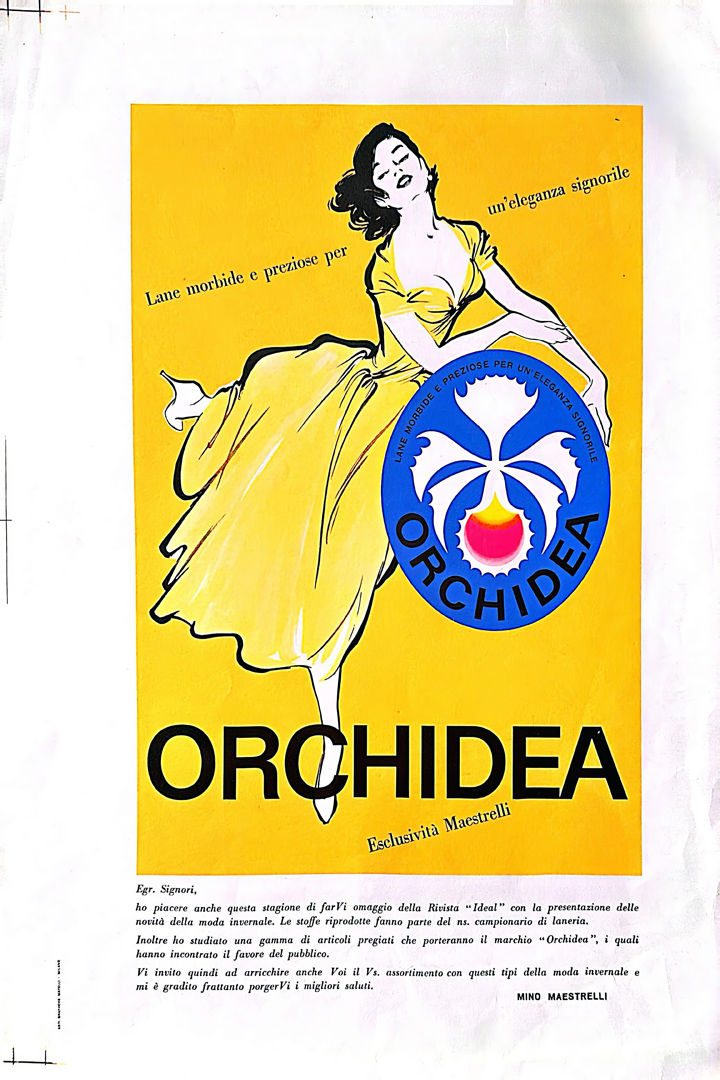

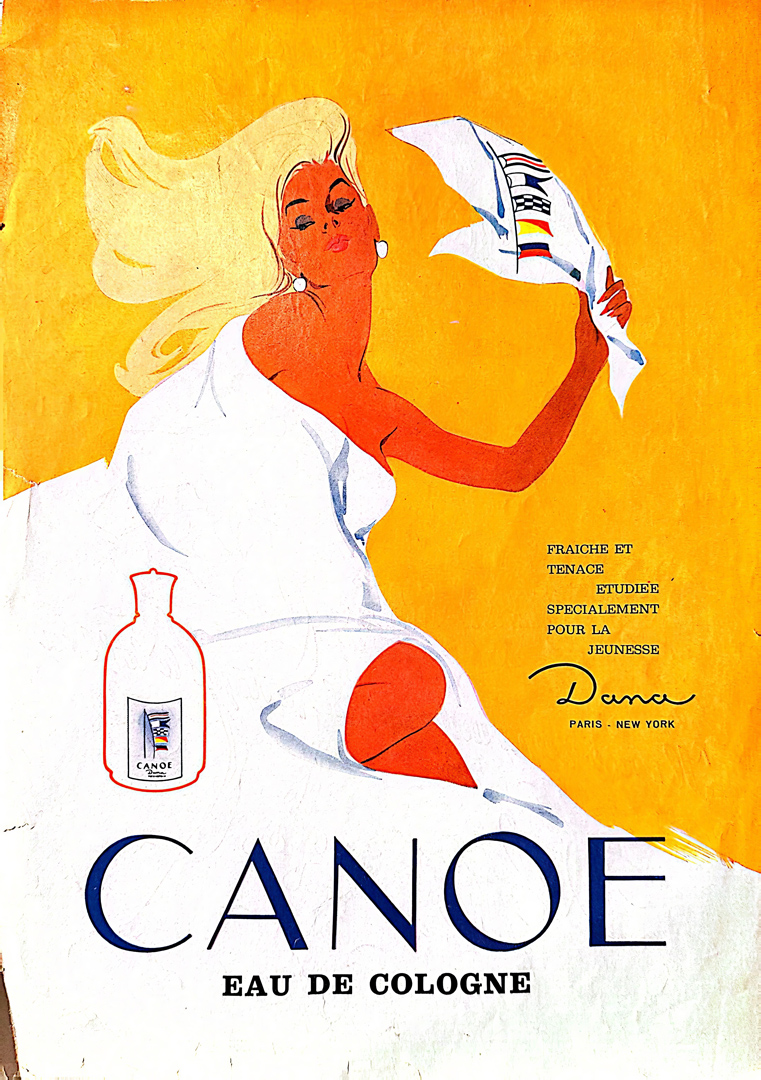

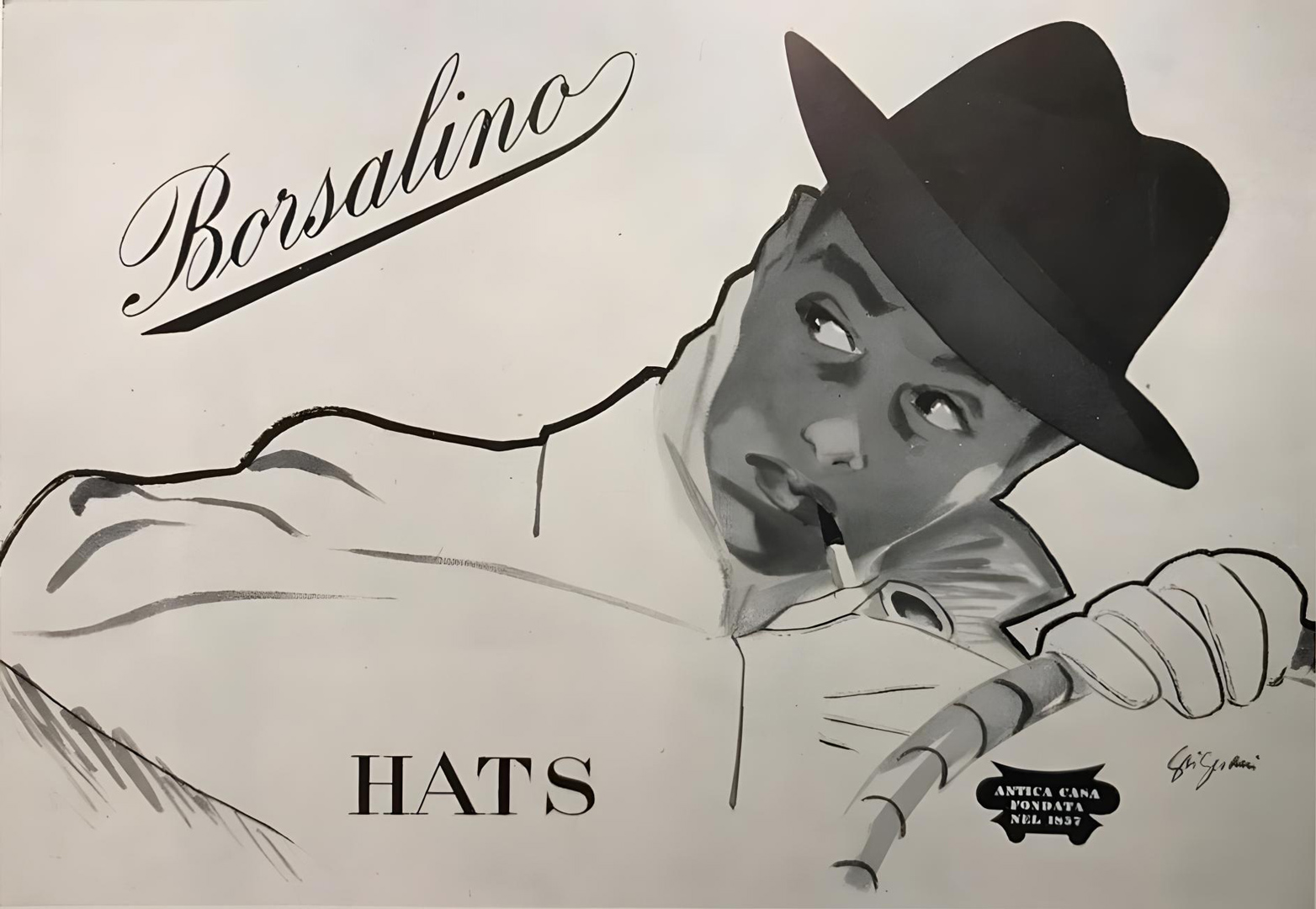

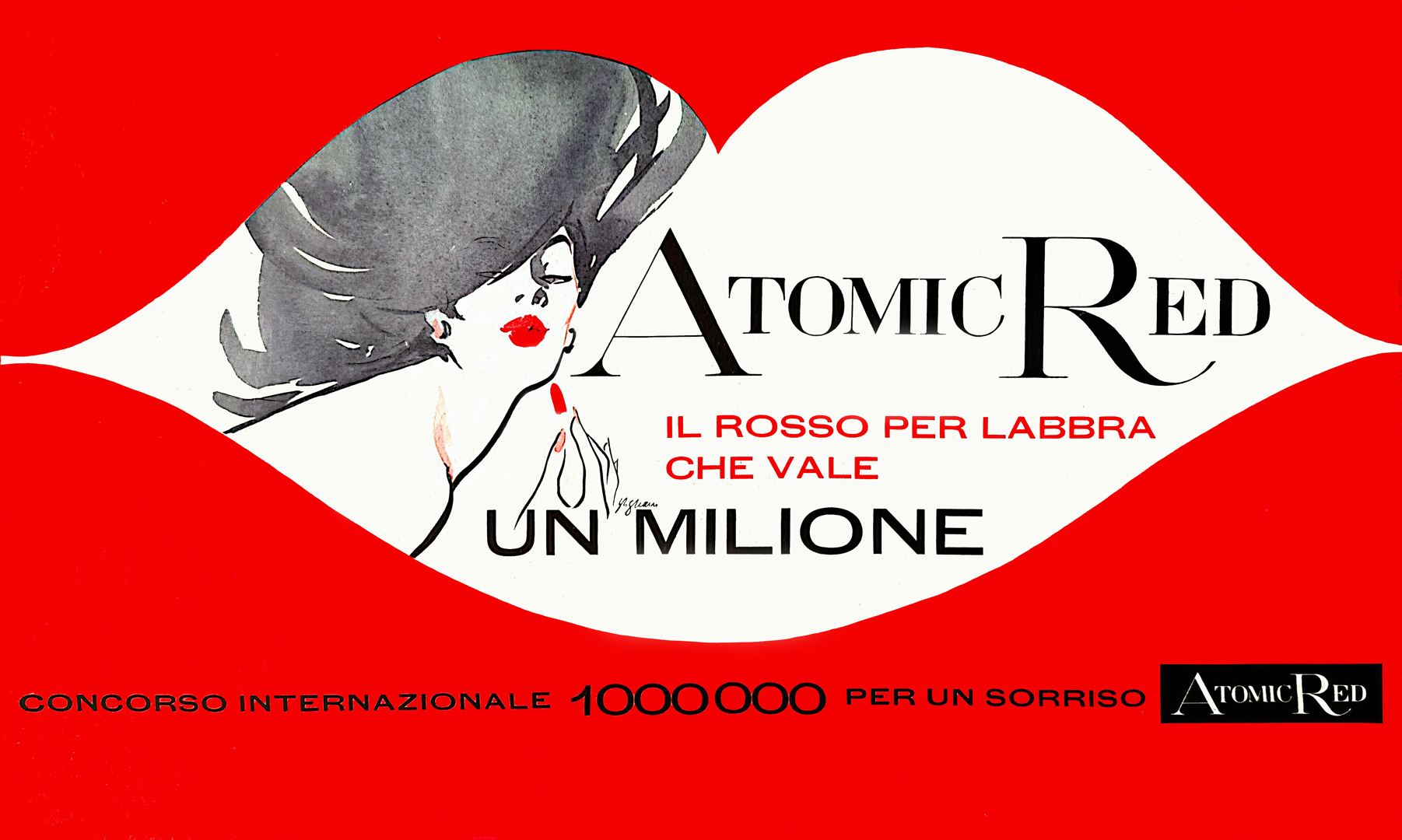

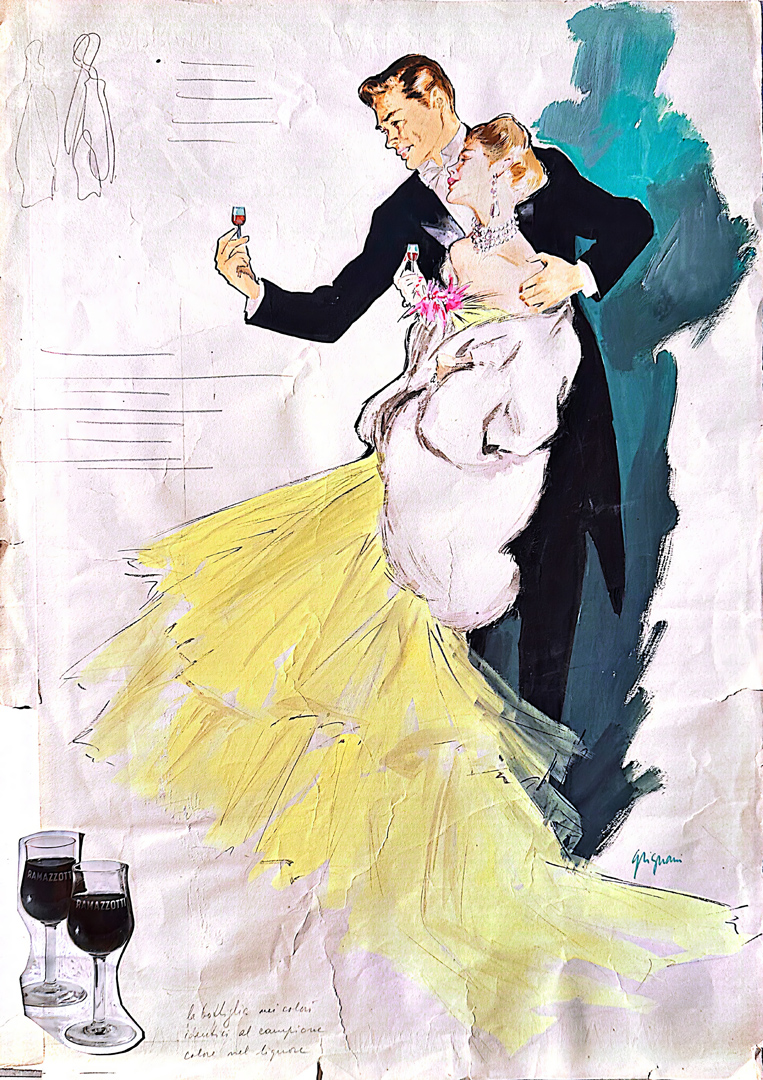

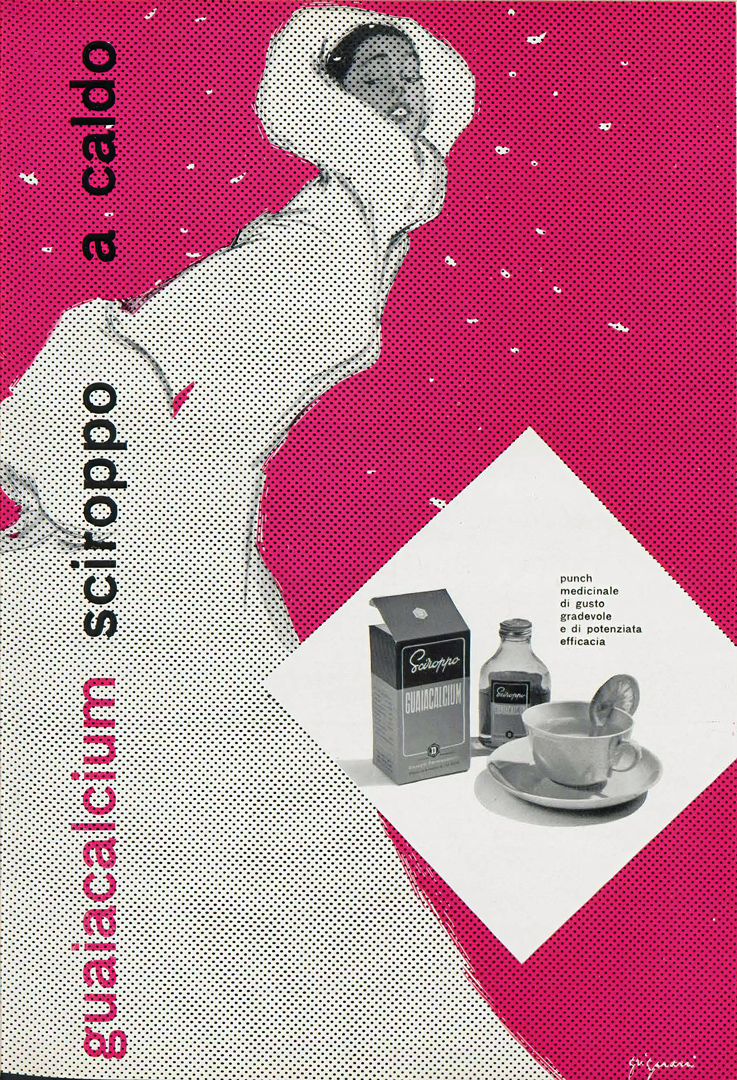

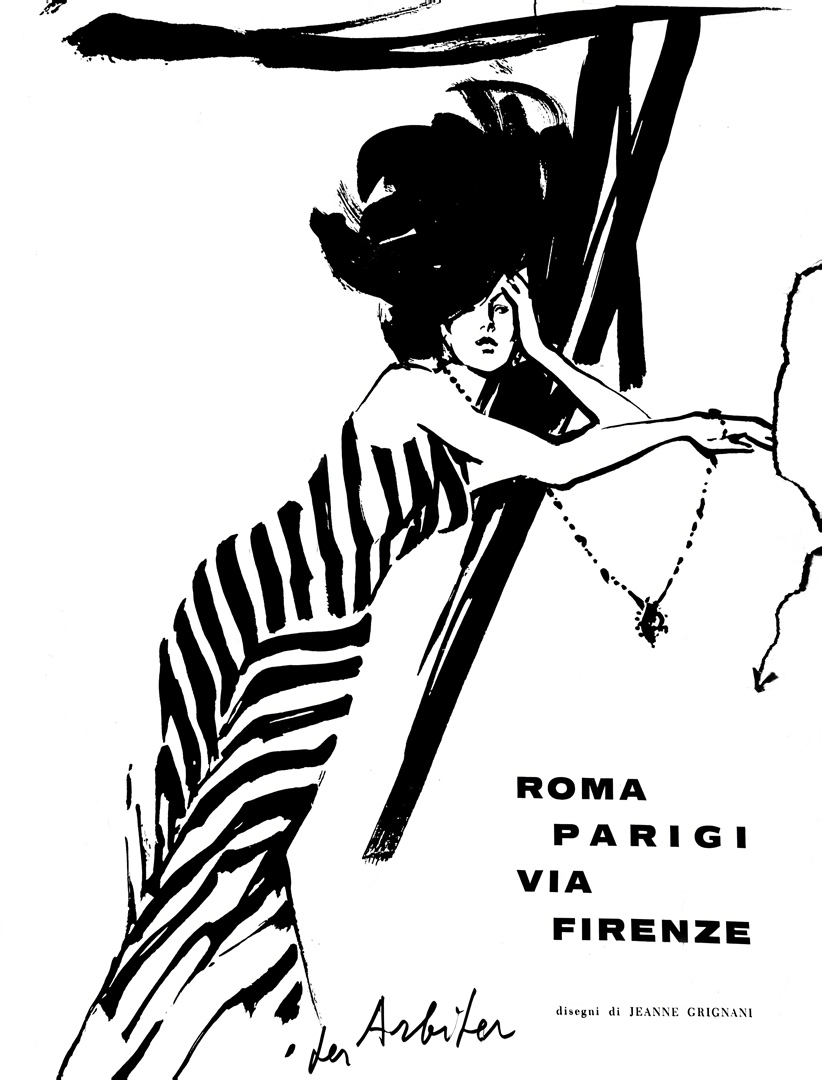

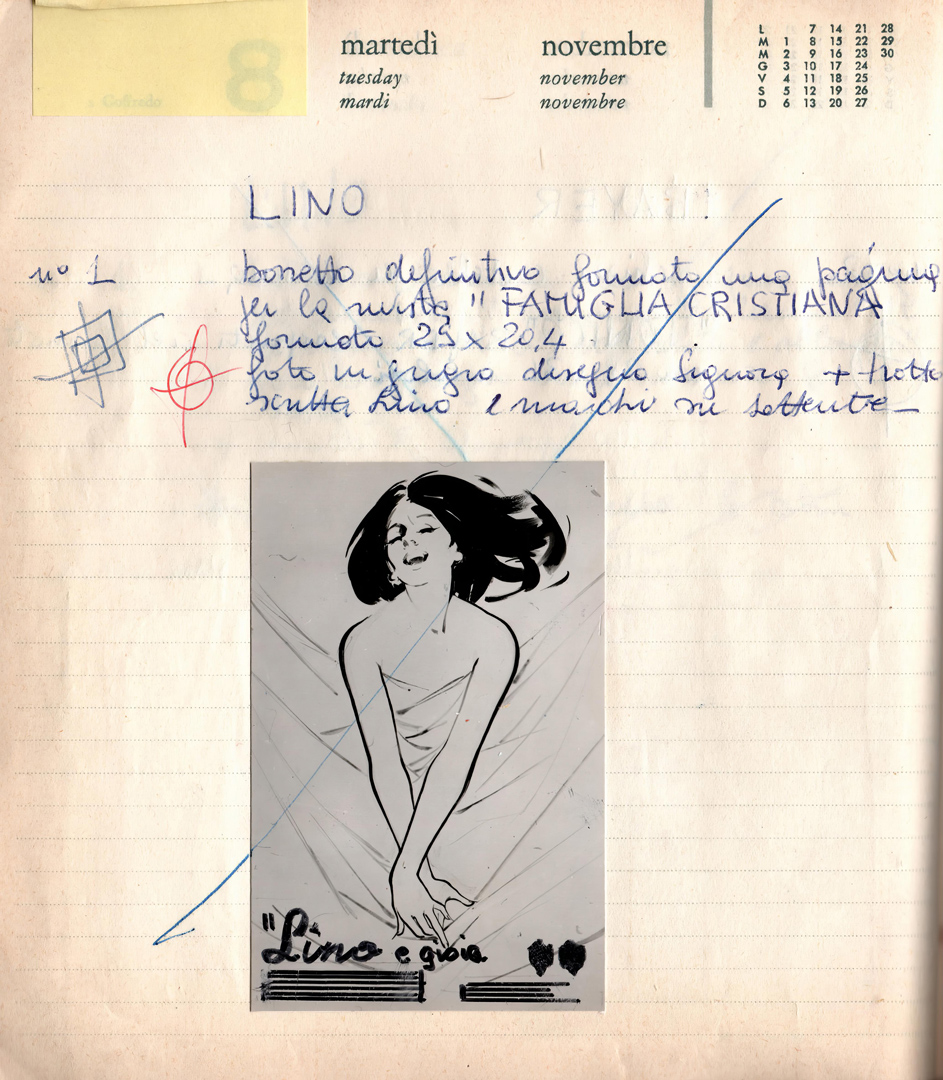

In Italy, Jeanne emerged as a distinguished figure in the world of fashion illustration and poster design. Her professional career spanned from 1945 until the late 1960s. During the 1950s, she crafted some of the most exquisite Italian fashion posters, which not only showcased the exceptional quality of Italian style but also solidified her place in the industry. Her work was often featured alongside the likes of Brunetta, whom she deeply admired, in publications like Bemberg and ‘Fili’ (‘Threads’) edited by Domus. Jeanne lent her artistic talent to prominent national brands such as Pirelli, la Rinascente, Borsalino, Marzotto, Zegna, Singer, Necchi, Dompé, and many others. Her unwavering support for Franco, whom she married in 1942 (despite facing challenges and receiving crucial assistance from the Consulate due to her perceived ‘undesirable’ French origins), played a pivotal role in their creative journey.

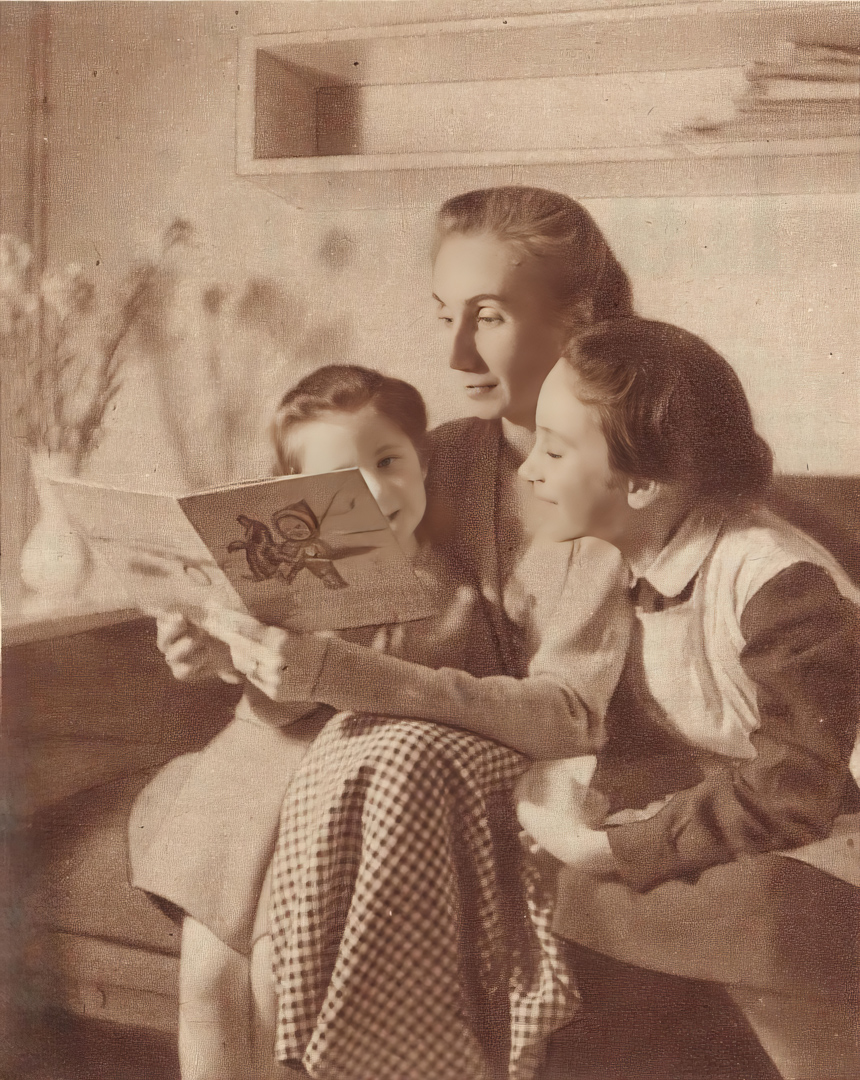

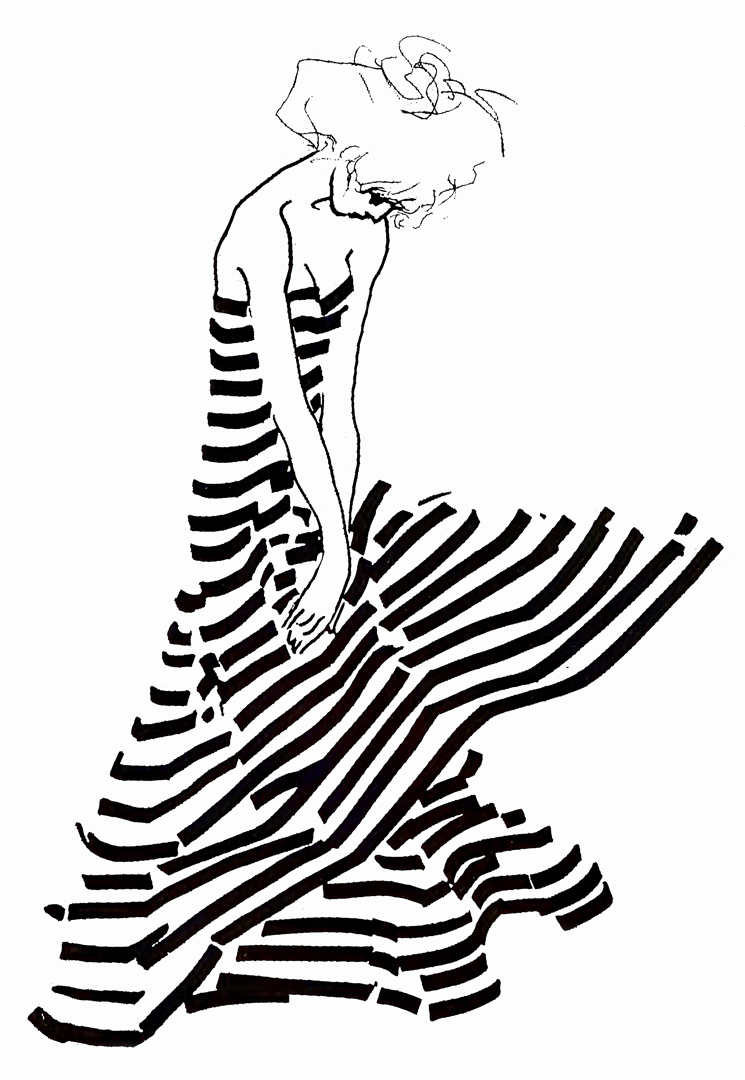

“In 1943, after the army was dissolved, I returned to Bergamo, where my wife and Daniela, who was born in those days, had been evacuated. What to do? My wife designed for fashion, I could help her inventing models; but I was not a tailor, I was interested in vertical lines, axes, horizontal relationships in the female figure; I was, in short, the Courrèges of that time. The first results were disastrous; my models looked like vaults. But little by little, observing my wife’s drawings, sweet figures with hands playing in the wind, of a feminine Art Nouveau style, I understood that I had to draw the lines from the flowing movements of the figure, and from the coordination of the decorative relationships. Thus, until 1946, we lived off this work.” [I]

In the initial stages, Jeanne’s artistic style had a somewhat scholastic quality to it. However, Franco likely recognized her untapped artistic potential. He made a habit of bringing her stacks of American magazines featuring inserts by talented designers, as he had subscribed to the Sunday insert of the New York Times (from the Italian-French magazine ‘arte e società’, 6/7, 1973), but also to other international fashion, design and graphics magazines such as Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Graphis. Jeanne eagerly immersed herself in studying these inserts with great enthusiasm and interest.

Jeanne Grignani garnered substantial acclaim during her career, exemplified by her 1960 achievement of winning the prestigious ‘Rossana Prize – art in Fashion’ in Santa Margherita Ligure. She was recognized for “having presented creations of great taste and sketched with enviable skill”, earning her widespread admiration through numerous letters of commendation. But despite her accolades, Jeanne was not fond of public events and rarely ventured outside her home. She often preferred that Franco accept honours on her behalf. “They are extremely private people and hardly ever go out.” [a]. Her decision to abstain from attending fashion shows, however, emerged as one of her greatest strengths. It shielded her from external influences and allowed her artistic expression to flourish:

“She is unique among fashion illustrators; she is never seen at fashion shows or in the high-society salons of haute couture. Serene, at home, she invents fashion, she intuits it. And she is never out of date, perhaps precisely because she draws on her imagination rather than rushed notes.”

Umberto Panin, ‘Gioia’, n°18, 1953

Jeanne’s creative contributions extended to enhancing some of her husband’s advertisements. Her influence was particularly notable in Franco’s receipt of the Palma d’Oro in 1959 for Necchi’s highly successful advertising campaign.

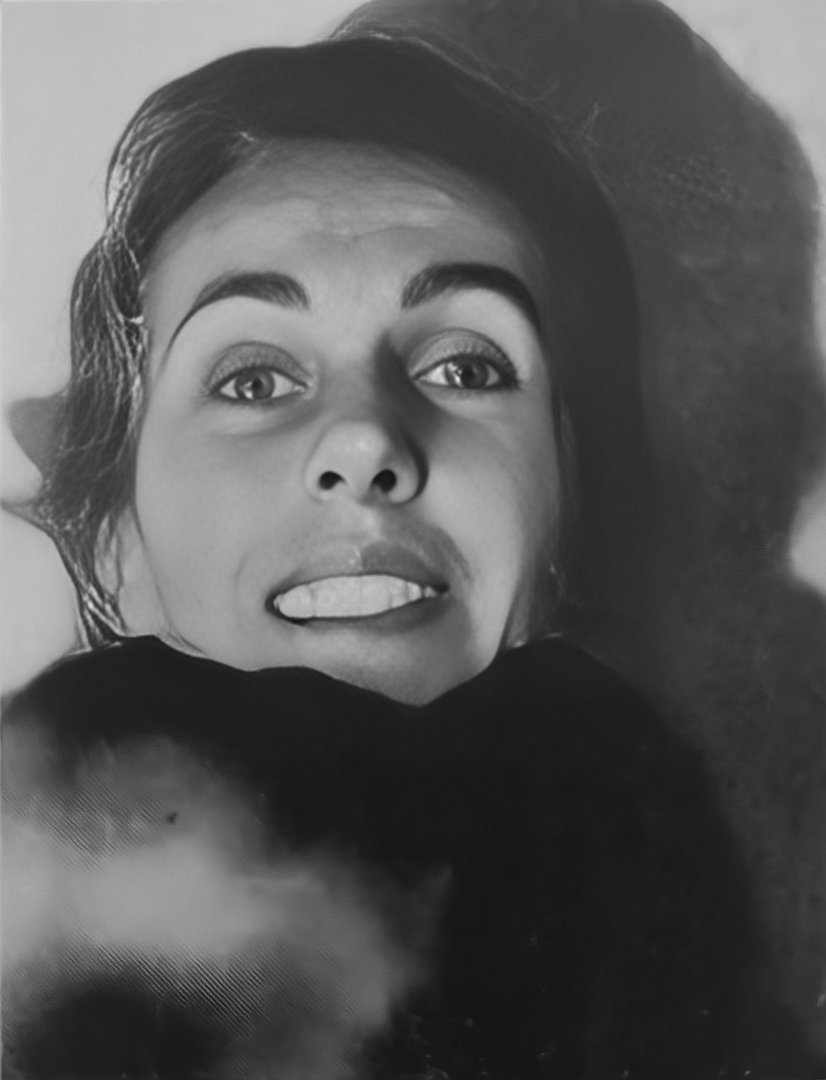

I know she admired René Gruau, but Jeanne had a distinctive style characterized by a lighter touch. The women she depicted exuded remarkable femininity, they were thin as if they had no weight (“seem to proceed lightly on spring meadows” – [a]). They were often affectionately referred to as “shampoo women” by my grandfather, a term that set them apart from the prevailing style of the time. One of the defining traits that makes Jeanne Grignani’s illustrations so captivating and timeless is the dynamic quality of her figures and scenes. Instead of static compositions, her work often subtly suggests movement. The female figures Jeanne created seem to mirror her own elegant and refined presence: her belief in the advertising motto ‘dress well’ (‘vesti bene‘) was so strong that I never once saw my grandmother without her cherished high-heeled shoes – a true passion of hers. She even recounted a wartime anecdote during a bombing raid on Milan when she fearlessly retraced her steps on a bicycle to retrieve a box of brand-new shoes that had fallen along her way…

Antonio Boggeri, the visionary behind the legendary Studio Boggeri, which opened its doors in 1933 and went on to become one of the world’s finest and most influential design studios, collaborated closely with both Jeanne and Franco. In 1954, he penned an article titled “Jeanne & Franco Grignani”, which was featured in the Swiss magazine Graphis, issue n° 56. Graphis was dedicated to showcasing and promoting the works of outstanding talents in international graphic design, advertising, photography, art, and illustration.

In this article, Boggeri highlighted the discretion and near-secrecy that defined the design process and the professional relationship within this “perfect duet”, who signed their works simply as ‘Grignani’. Jeanne Grignani preferred not to engage directly with clients, who normally approached Franco Grignani for the complete design of posters, advertisements, and more, thus leading to the observation that “in fact very few people, even in Milan, know that there are two Grignanis; though everybody, and especially the feminine world, is familiar with her designs, ubiquitous in the fashion journals”.

These factors have contributed to the ongoing challenge of correctly attributing Jeanne Grignani’s works.

The article was originally published in English, as well as in French and German:

To compare J. and F. Grignani with other famous artist couples would be interesting only if something more definite were known about their method of working. For my own part, however, I should be at a loss to say by what system of collaboration their finished designs are really produced; and though I have known them for many years, I have never pried very deeply into a secret which has seemed to me of little importance to those who are primarily interested in the results.

Jeanne and Franco Grignani are husband and wife, and it may be that in their work they quarrel and make up like any other mortal couple. But the facts behind their artistic relationship – whether the personality of the one has influenced the other, whether the wife exercises a critical function, whether she contributes ideas and argues about them, and what would have become of the one without the other’s company – these things are difficult to ascertain. More has therefore been written about their visible accomplishments than about the interplay of their characters, the stimulating effect, say, of a romantic temperament on one of more meditative bent, or the reactions of contrasting disposition.

The one thing that is clear is that the more pictorial qualities of Jeanne’s work harmonize perfectly with her husband’s fine graphic sensibility. The dreamy elegance of her figures seems made to measure for the subtle tastes of Franco Grignani; and in fifteen years of unbroken collaboration their two voices have been trained to blend in a perfect duet. The ideas are mostly the husband’s, but when his graphic compositions centre upon a figure, he asks his wife to supply it. It is here, I imagine, that discussions begin on how the figure is to look, though no-one has so far overheard them.

Jeanne Grignani was born in Russia and went as a child to France before settling in Milan. An accomplished pen might digress very charmingly on a past so individual and rich in promise. And it seems significant that in the female figures that blossom from her brush there is something of the energy-packed fragility, the nervous delicacy of the slightly mysterious persona who produced them.

There is, I am told, a surprising correlation between the characters of children and the graphic world of their drawings. I think, perhaps, that when an artist’s work comes within the compass of a single design, a design that repeats itself incessantly with variations drawn only from passing fashions, this unique image must in some way be an image of the artist, just as the child’s drawing is the spontaneous expression of its own identity. That is why I always see, in the figures drawn by Jeanne G., a little of herself.

Franco’s work is very different; its relation to the free fantasy of a fashion drawing is that of a caged bird to a swallow. His is the world of graphic precision: rigorous, subtle, made up only of pure apperceptions, minute optical vibrations: things not quickly learnt and impossible to impart.

Grignani knows his keyboard as well as any pianist. He knows that sometimes a drawing is needed, a very definite drawing, and he has beside him, as in a fairy story, the very hand that can provide it. Then, with the drawing before him, discussed and revised once or half a dozen times, he begins his task of assimilation, absorbing completely what was at first extraneous to him; and in the end the finished work seems as though it must have come in a flash, conceived and projected by a single mind. And in fact very few people, even in Milan, know that there are two Grignani’s; though everybody, and especially the feminine world, is familiar with her designs, ubiquitous in the fashion journals.

It was out of this closed world that her husband offered her egress, and it is a pity only that the instances of such a fruitful collaboration are not more frequent. For the examples are rare in which drawings come into their full rights and are integrated in this way in graphic compositions, blended on an equal footing with the chosen elements of modern art.

More pics of the ‘Vesti Bene, Vesti LANA’ advertising campaign can be browsed from the website of the Cirulli Foundation.

Jeanne Grignani’s sketches are set to be showcased in 2020 at the Pirelli Foundation (re-scheduled), as part of an exhibition that pays tribute to prominent women of the 1900s, showcasing their remarkable contributions to creativity and innovation.

further related posts:

[*] courtesy of Daniela Grignani

[°] courtesy of Daniela Grignani; digitalization credits: Cristina Simone, IUAV, 2024

[a] from Gioia, n°18, 1953

[b] from 2a Mostra Nazionale Artisti Publicitari, 1959

[c] & featured pic from Italian Ways: 1 & 2

[d] from Graphis issue n° 33, 1950

[7] AIAP / CDPG Centro di Documentazione sul Progetto Grafico, courtesy of Lorenzo Grazzani

[I] ITA original text from the Italian-French magazine ‘arte e società’, 6/7, 1973: “Nel 1943, dissolto l’esercito, ritorno a Bergamo dove vivevano sfollate mia moglie e Daniela nata in quei giorni. Che fare? Mia moglie disegnava per la moda, potevo aiutarla ad inventare modelli; ma io non ero un sarto, mi interessavano linee verticali, assi, rapporti orizzontali nella figura femminile; ero, insomma, il Courrèges di allora. I primi risultati furono disastrosi: i miei modelli sembravano casseforti. Ma adagio adagio, osservando i disegni di mia moglie, dolci figure dalle mani giuocate nel vento, di una femminilità liberty, capii che le linee dovevo ricavarle nei movimenti fluttuanti della figura, e dal coordinamento dei rapporti decorativi. Così, fino al 1946, vivemmo di questo lavoro.”

Last Updated on 15/01/2025 by Emiliano